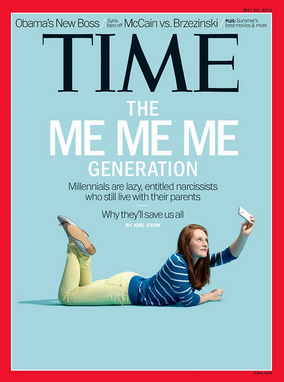

A popular version of the undying nostalgia for a golden era gone by is the view that this era was a time when men were men, and children grew into adults at the proper time. These days you cannot go online and hope to be safe from a barrage of disparaging remarks about those lazy, narcissistic, entitled Millennials.

I have always felt that there was something telescopic about the very framing of the matter. We bemoan the decline of real men, real women, and real adults, often based simply on what we read about people we’ve never met in sources that have not earned our trust. We should dispense with such nonsense and refocus on energies and our minds on the sphere we actually live in.

But there’s being responsible with your focus, and then there’s hiding your head in the sand. Statisticians and scholars and journalists are often neglectful about the details of the parts which make up the whole of what they study. But it’s also hard to understand the parts of our lives without also understanding their relationship to the whole. So it isn’t a bad idea for the properly concerned parent, spouse, sibling, child, and neighbor to — cautiously — venture out to see what can be learned about the state of things beyond our field of view.

One of the biggest talking points around Millennials’ supposed inability to grow up is the notion that they stay in their parents’ homes far longer than people used to. It has been my experience that when people compare the present to the past, they will look back two generations at most. We are extremely myopic about what constitutes history or tradition. Sure enough, when I began to look into how “coresidence” of adult children with their parents has changed over time, most of the sources I found went back only twenty or thirty years. One particularly helpful one went back to the 60s. It showed an increase, though nothing epochal. And it was inflated somewhat by the fact that the data up to 1980 treated college students living in dorms as having left their parents’ home, while the data from 1983 to the present did not.

Thankfully, Tyler Cowen is correct that there really is a literature on everything. A particularly helpful paper in the literature on this subject looks at the question from 1880 to 1990. What they found was that the “median age at leaving home” was increasing up until World War II, after which it fell precipitously. It then rose from the 70s to the present, but by 1990 it had not even reached its pre-war level.

Everything about this paper points to an idea that can be encountered in the history of education, business, marriage, and many other places. This is the idea that it is the post-war period that was historically the most unusual, and the period from the 70s to the present, while not exactly a reversion to the past, is less radically different from it than the period that directly precedes it. For instance, the paper shows that the age at leaving home for men became radically more homogenous during that period than the periods before or after.

So you can see why it might not be the best idea to use it as a point of reference. I like that this paper goes back so far as 1880; in truth, I wish it went back even further. But in the 19th century and earlier, Americans largely lived in intergenerational farm homes, as the Amish still do today. Our post-agricultural, post-industrial era has very few apples to apples comparisons that are readily available to be made.

Nevertheless, the paper does a very good job exploring the many scenarios under which people ended up no longer living with their parents. An important emphasis the paper makes is the sharp decline in “nonvoluntary” causes of leaving a parents’ home — such as the sudden death of the parents, or “when poverty leads to the disintegration of the family household.”

The obvious reply, of course, is that people before 1940 were at least working, whereas today’s kids may just be playing video games and watching porn. Which brings us to the second question: just how unlikely is it for the young to be working?

Obviously child labor was essentially abolished before 1940, and public education was spread more widely. So more and more people reached the age of 18 with little to no work experience at all.

First, it should be noted that the employment to population ratio of “prime age” people has fluctuated a great deal over the past 40 years, for reasons unlikely to have anything to do with generational explanations. At present, at 77 percent, it is in a fairly average position for the time period; not very high, not very low. Of course this includes very few of today’s young — as this is for people between 25 and 54. But it’s worth noting as a point of reference. Also worth noting is the labor force participation rate for this group, which is quite high for the 60 year period I could find data for.

The labor force participation rate for teenagers, aged 16-19, is way down relative to the past 60 years, with the collapse starting in about 1990. What’s more, the unemployment rate among this group is currently at 18 percent, meaning a small fraction of 16-19 year olds are trying to work and only 80 percent or so of that fraction even finds work. That is indeed troubling — whether it’s because of the expectations set for people this age, or labor regulations, or something else, I couldn’t say. But only 28 percent of 16-19 year olds are getting any experience in the working world, and I don’t think that’s a good thing.

The labor force participation rate for 20-24 year olds, however, is quite normal for the past 60 years. The unemployment rate is on the high side, at about 10 percent. But around 70 percent of young twenty-somethings — the very group most people are talking about when they speak of Millennials — are either working, or trying to. If the rate is relatively low for men, who used to have participation rates in the high 80s, it is relatively high for women, who of course began entering the workforce in large numbers in the middle of the century. So broadly speaking, the twenty-somethings of today, compared to their predecessors, are out in the working world in a big way. The participation rate only increases for 25-34 year olds, and the unemployment rate falls by half.

These of course are just a couple of dimensions from which to look at the many accusations leveled at the young today. Megan McArdle, for instance, thinks they are all too coddled and thus risk-averse. But again I have to ask: compared to what? There were always children uncomfortable with taking a single step off of the life path set for them by their parents and their community. I agree that the free range kids and the homeschooling movements are valuable correctives to the modern conveyor belt, but I wonder how deleterious the latter has really been. Are there really so many more risk-averse people than 50, 100, 200, 300, 500 years ago? How would we begin to answer that question? What’s the right amount of risk-aversion, and the right number of highly risk-averse people?

The bottom line, for a porcher, should be that you need not look to some vast, generational explanation of the circumstances you see in front of you. If you have a son or daughter who is having trouble finding a job, or finishing their education, or meeting people, odds are that looking to vast social forces will not tell you much. There have always been sons and daughters who left the home later rather than sooner, for many reasons. You are more likely to locate those reasons through what you know about your child by being present in their life from its very beginning, and in the circumstances of their life and yours.

Adam, that’s a fine piece of writing.

My guess as to the rising teen unemployment rate would be since 1990 we’ve imported roughly 20M Mexicans and other Central Americans. It’s likely that those jobs they’ve taken in construction and lawn maintenance were jobs that could’ve been done by either teens on summer break or by low to medium IQ whites and blacks who would leave HS and immediately go into the trades. Those same immigrants are much less of a threat to the middle to high IQ-ers who are in the professional classes.

Chris,

Thanks for your kind words 🙂

It’s highly unlikely that that’s what’s going on, with regard to teens. The big turn of the 20th century wave in immigration didn’t bring up teen unemployment, and that was huge, in terms of percentage of the population. Labor regulations seem like the far more likely culprit, though I’m not sure what changed there in particular in the 90s either.

Comments are closed.