Grand Rapids, MI

Leonard Cohen has done his last show, composed his last song, and breathed his last breath. When the news popped up on the screen of my laptop that Leonard Cohen had died, I reflexively pulled down the old CD and played “Hallelujah.” It is not the first time that I have turned to that CD, and specifically to that song, when something happened that struck a deep chord.

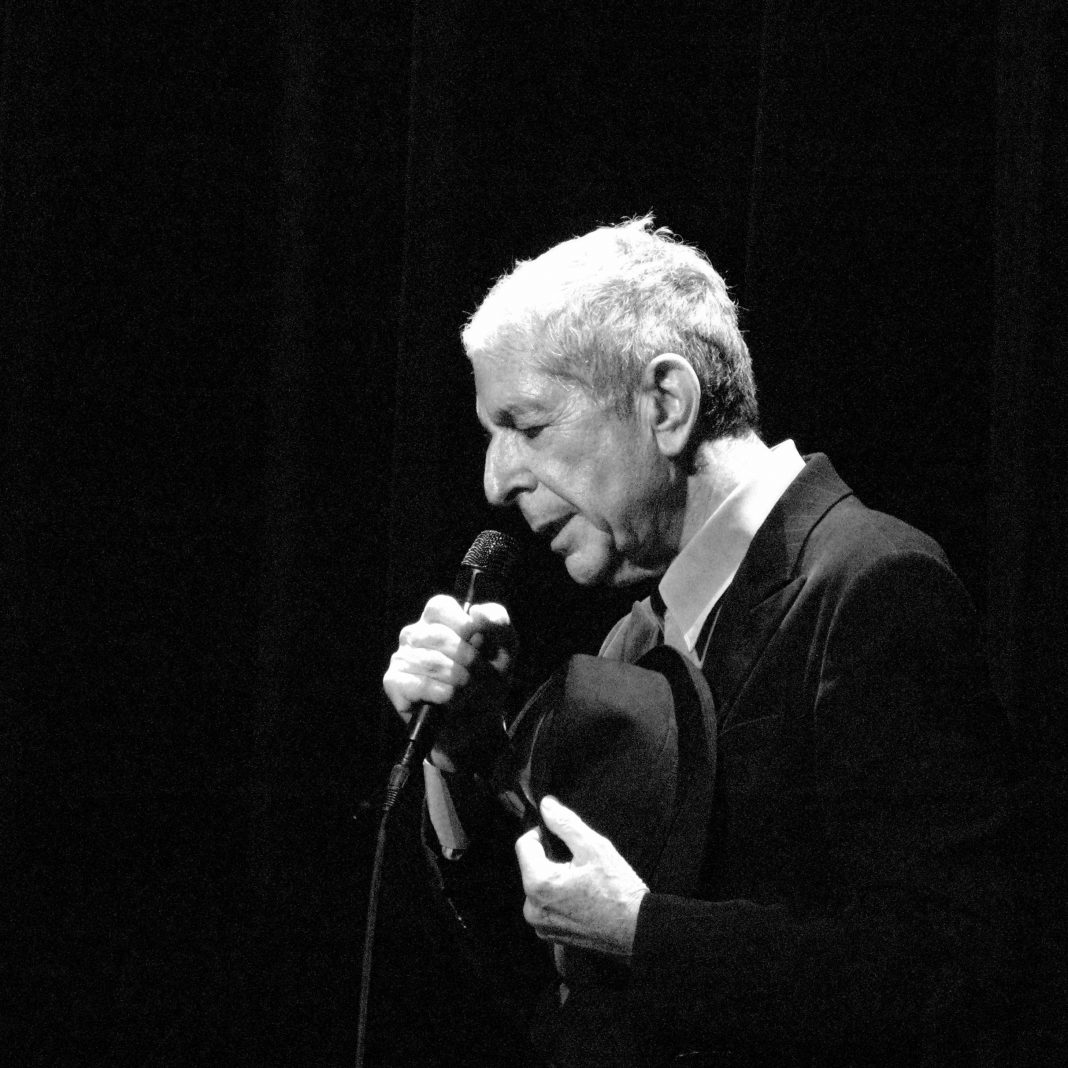

Even when listening to this song alone at my computer, I know why millions of others like me find Cohen’s music irresistible. His songs can capture a crowd just as easily as they can drive a lone listener into pensive silence. We sing along with lines whose subtle allusions are beyond our reach, and we quote lines that go deeper every time we repeat them. Leonard didn’t really sing. He recited, chanted words to music until they wove a web around us so that, even if we didn’t always hear the music, we couldn’t ignore the words. And sometimes when we were too distracted to hear the words, we still could feel the force of them in the music.

Leonard Cohen’s music is a tapestry of contrasts. He was brazenly sacrilegious sometimes, but also tenderly devout at others. He dared to put into words the horrors of our time about which it is difficult to speak, and he dared to speak of infatuation in words that can make the cold heart flutter. It is known that Leonard Cohen combed over his words until they felt nearly right, but he was not careful in what he revealed, nor was he delicate when he pointed a finger and accused. Who knows whether he thought of himself more in the tradition of David the Psalmist or Nathan the Prophet, but there is no doubt that Leonard Cohen could make his listeners squirm. He could stir guilt in a generation that didn’t believe in guilt anymore. He could reignite the longing for love in a generation that, in its own sexual emancipation, had discarded romance as a folly from the past.

Just when we thought we knew where he was going, when we were completely in step with the chanting rhythms of Cohen’s gravel voice, he could change the direction and point somewhere else. He was the poet of ambiguity, the prophet of the broken. But it is the gasp of a broken Hallelujah, repeated until it comes into harmony again, that stands out most memorably in the song that became his best known. Leonard was a modern oracle whose enigmatic poetry convinced us that we were getting a message from somewhere, and the message was meant just for us.

It is obvious enough that Cohen had something profound in mind, when he added a refrain of “Hallelujah” to verses about David and Bathsheba’s affair, Samson and Delilah’s betrayal, and his own infatuations and disillusionments in search of love. His songs stirred us up and reminded us of something in our collective memory. But the “Hallelujah” repeated again and again and again. What was that about? Why nearly thirty times in the course of one song?

Clearly Cohen was not imitating Handel’s famous chorus because Cohen’s “Hallelujah” was not standup court music. And it was not a seductive “Hallelujah” like the one sung in an ad by actors dressed like nuns trying to hawk laptop computers with a bitten apple on the lid. Cohen’s Hallelujah was more like the ones he heard as a devout boy, faithfully attending services on holy days. If we think that repeating the Hallelujah nearly thirty times in one song is a lot, we need only consider that Leonard had repeated these same words thousands of times when he stood with the congregation during the Great Hallel. He probably knew large portions of the service by heart, and he certainly knew the reflexive raise of voices in the congregation’s refrain of “Hallelujah.”

Cohen was imprinted as a boy with the awareness that the only fitting response to a long recitation of passing days and impermanence, the only fitting response as the Paschal lamb was being sacrificed all over again, was an appeal of a different sort to steadfast love and enduring mercy. In the face of this Cohen admits that the best he can come up with himself is a “broken Hallelujah,” but Hallelujah it is.

Loenard Cohen was not indifferent to his own fame. He moved with the enthusiasm of his concert crowds. He must have known the number of records he sold. But he, like everyone who is blessed to grow old, also knew of his own impermanence. While it may not be the most famous of his songs, one of the most profound is “Going Home.” It is a dialogue with the divine. In it Cohen once again compares himself to David, the Psalmist – the sportsman whose aim topped Goliath, the sheperd from Judea, and the king with clay feet covered by the royal robes. He confesses what he himself wanted to accomplish as an artist.

He wants to write a love song

An Anthem of forgiving

A manual for living with defeat

A cry above the suffering

A sacrifice recovering

But that isn’t what I need him

To complete

In the end Leonard Cohen recognized that the burden of the artist is no longer on his shoulders; the duty to bring some new insight to the world does not need to drive him anymore. The sorrows of the past do not need to shape his sorrow now. He is ready to go home and leave all these things behind. He is ready to go behind the curtain – into the holy place. Even in this gesture of facing his own mortality Leonard Cohen once more helps us reflect on impermanence, to which he was willing to consign his efforts and his gifts. And he is willing to speak a hallelujah to what endures.

Mary VanderGoot is a retired psychologist and active writer living in West Michigan.

Cohen’s death means, among other things, that the year keeps getting more costly. May it please God the year ends before the price is too high.

I wouldn’t say “Hallelujah” stands or falls on the phrase “with nothing on my tongue but ‘Hallelujah,'” but I am partial to versions that include it. It’s really something.

Here’s Cohen himself on the song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGpumEYjDAc

Comments are closed.