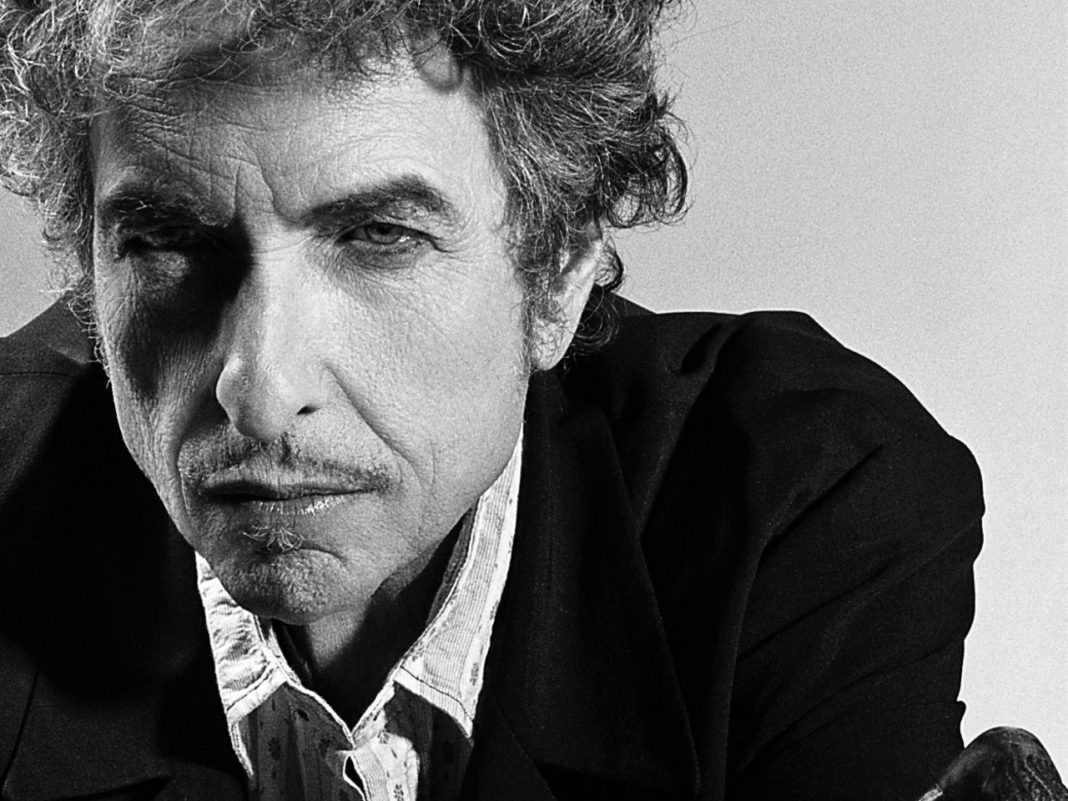

Bob Dylan: The Lyrics, 1961-2012

Reviewed by Robert Dean Lurie

I am one of the infected; I am a Bob Dylan fan.

It wasn’t always this way. When I first encountered Dylan’s music in my teens, I heard what the critics hear: a bleating, off-key harmonica, a voice scraping the collective chalkboard, repetitive melodies and uninspired musical backing. But something shifted upon hearing his 1975 track “Tangled up in Blue.” Ostensibly the tale of two bohemian drifters falling in and out of love, the song seems to tell a much older story. “Then he started into dealing with slaves,” Dylan sings near the end, “and something inside of him died.” An arresting metaphor. Is this a nod to Rimbaud’s (alleged) journey from poet to slave trader? Is the “he” in this verse synonymous with the “I” that narrates the rest of the song? Puzzling over these little mysteries is a big part of what makes being a fan so much fun. It also goes a long way in explaining why Dylan has remained the distraction of choice for generations of English majors procrastinating on their more formal studies.

But what happens when the distraction becomes the object of formal study itself? Dylan’s work can be poetic, yes, but is it poetry? Is he truly deserving of his recently awarded Nobel Prize in Literature?

In determining an answer, we are well-served by the recently published Bob Dylan: The Lyrics, 1961-2002, a near-comprehensive collection of Dylan’s song lyrics spanning his debut up through Tempest, his most recent album of original material. Refreshingly, readers have been spared the usual glowing introductions from Rolling Stone contributing editors, or lengthy “story behind each song” essays. Instead, we get the album art and the lyrics, cleanly typed. It is an aesthetically lovely book.

As to that question: Is Bob Dylan a poet? It depends on where you look. Many of Dylan’s acolytes, including several writers and English professors who ought to know better, have highlighted his logorrheic mid-1960s work as evidence of his Nobel-worthiness. “Desolation Row” is often cited as one of his more profound turns, and, yes, it is a marvelous song, but its flimsiness as a poem becomes starkly clear when viewed on the printed page. Crowded with playful, often nonsensical references to Cinderella, Bette Davis, the Good Samaritan, Ophelia, Einstein, The Phantom of the Opera, Casanova, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot, it reads like a stoned mash-up of The Norton Anthology of Literature and People Magazine.

More successful is “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”:

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

If that is not literature, then literature is at least not shamed by the comparison. (And yet, as with the more well-known “Mr. Tambourine Man,” Dylan’s descriptive imagery can be a bit “off.” How exactly does one break one’s tongue?)

Perhaps I am showing my bias here. I prefer the Dylan that came out the other side of this mess: the songwriter who stopped trying to say something important about his generation and got down to the business of exploring the workings of the human heart. I’m partial to the Bob Dylan of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Blood on the Tracks, and, later, Time out of Mind, the Dylan who revisited the traditionals on Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong and put a fittingly rough-hewn spin on the Great American Songbook on Shadows in the Night and Falling Angels. Unlike many, I view his late-1970s conversion to Christianity as a galvanizing moment for his writing and his manhood, not as some sort of lapse or betrayal. I don’t want to saddle him with undue hyperbole, but I like this man very much. His work has affected me.

To be a Dylan fan, one must be willing to put up with a lot of subpar material in anticipation of the occasional payoff. It is this way with his albums, concerts, and even individual songs, which can careen from banal to profound in the space of a verse. If you’re looking for a more dependable rate of return from your pop songwriters, you’d be advised to turn to Leonard Cohen or perhaps Townes Van Zandt. Dylan fans are born gamblers.

An example: perusing The Lyrics, you might land on “Wiggle Wiggle” (“Wiggle wiggle wiggle like a bowl of soup / Wiggle wiggle wiggle like a rolling hoop”) and draw one conclusion. Or, you might land on “Every Grain of Sand” and draw another:

Don’t have the inclination to look back on any mistake

Like Cain, I now behold the chain of events I must break

In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand

In every leaf that trembles, in every grain of sand.

That’s the sort of payoff I’m talking about.

I am glad that Bob Dylan won the Nobel. His work may not be literature, but given the increasingly arbitrary roster of awardees for the other Nobel prizes (the Peace Prize being the glaring example), the committee has already demonstrated an elastic interpretation of its qualifying criteria. To add to that sense of randomness, a good number of Dylan’s predecessors in the literary category seem to have been selected by throwing darts at a map of Europe and then searching Wikipedia for the nearest living writer. So why not give the prize to an enormously popular American songwriter conversant in Coleridge and Tacitus, one whose work has nudged more than a few people, your reviewer included, into actually studying literature. All due respect to previous awardee Svetlana Alexievich, I’m just not sure she has had that same level of reach. In this heathen age, absent the giants who once roamed the earth (Mann, Faulkner, Eliot, et al.), this may be as good as it gets.

At any rate, The Lyrics provides ample fodder for both the critics and the partisans. It is, simply put, one man’s life’s work, containing all the triumphs and disasters that that entails.

A sensible look at the so called problem of Dylan as a poet. His influence, his often brilliant adaption of low and high culture and merging them, but also his occasional clumsiness, which is inherent to his off the cuff style of working, where he goes faster than most but occasinally also wanders hopelessly, always dependent on intuition more then theory, it all marks him as one of our greatest writers. And the academics should finally be aware that their lack of regard for how a poem or sentence sounds and which significance it has in broader cultural sense hurts literature, not the fact that the Nobel Prize has been given to someone from ‘outside’. The only objection against this article would be that it dares to call one of the most beautiful poems of the last century flimsy, Desolation Row should be read aloud in every high school! I think Ginsberg suggested such.

Nonsensical references ?

Don’t criticize what you don’t understand …

The references are clearly explained in the last verse.

These names are referring to various members of the Baez entourage and protest acolytes.

Do a bit of research dimwit

I appreciate your point of view,but to some degree come down on the other side…less impressed with the “Sinatra” material, for example. I think “pay off” is a good principle with Dylan, He seldom doesn’t pay off…of course, he pays in blood…” not his own. I disagree with your perspective on the Desolation Row era material…it may not scan well, but as song, imagery, and associative poetry it is exceptional.

“Is he truly deserving of his recently awarded Nobel Prize in Literature?”

A better question would be if the Nobel Prize in Literature is deserving of an awardee like Bob Dylan. He is the Chuck Norris of poetry, making the impossible seem if not painless at least routinely doable. Remember, if his lyrics don’t make sense the problem is never the lyrics. Its our imagination.

The way he says the words is a part of the point he is trying to make with the words themselves. It is a whole ‘nother dimension of literature. If his work is not literature then its only because we need something higher to call it.

Comments are closed.