BURNED-OVER DISTRICT, NY — As rumors of rogue electors spike the December air, I offer this piece from 2001, which is included in my Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from An Alternative America, which of course you, as a literate American, already own. (Sorry for the extortionate price.) By the way, my wife was John Hospers’s assistant and friend at USC, so I have a special fondness for electors who wander off into third-party pastures.

The Electoral College has shut down for another four years. Gorey fantasies of “faithless electors” escaping their ironclad lockboxes and bolting from Bush to Prince Albert have come to naught. Apparently the Republicans have learned something about vetting electors since 1972, when a GOP elector deserted–and did so quite predictably. For the ’72 renegade, Roger Lea MacBride, had written a book 20 years earlier in which he praised the conscience-driven elector as a vital, if all too rare, feature of the Electoral College. Sometimes authors mean what they write.

As a lad of 16, Roger MacBride, a Coke-bottle spectacled son of a Reader’s Digest editor, fell under the spell of a family friend, Rose Wilder Lane, daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder of Little House on the Prairie fame. Rose, a libertarian globetrotter and popular journalist who once rejected a marriage proposal from King Zog of Albania, had become a cause celebre when she refused to accept a Social Security number. (“I will have nothing to do with that Ponzi fraud because it is treason; it will wreck this country as it wrecked Germany. I won’t have it; you can’t make me,” she declared.)

The childless Lane made MacBride her “adopted grandson,” a winning lottery ticket if ever there were one. He became heir to the Little House fortune, which is ample enough to build big houses from one end of South Dakota to the other.

As a young lawyer, MacBride wrote a little book titled The American Electoral College (1953) in which he proposed a “district system” similar to that now in use in Nebraska and Maine; electors would be awarded by congressional district, with two bonus electors given to the winner of the state. “The district mode was mostly, if not exclusively, in view when the Constitution was framed and adopted,” explained James Madison, but largely abandoned as states sought to maximize their relative influence by delivering their electors as a bloc to the victor.

MacBride deplored deviations from the Founders’ intent, for instance the fact that “Electors almost never exercis[e] independent judgment.” They had become mere “mechanical men,” drones who in some states are forbidden by law from voting their conscience.

MacBride urged an “attempt to restore to the members of the Electoral College some of the function of independent thinking and action assigned to them by the Federal Convention.” In this he was echoing Madison, who in 1823 had endorsed the independence of electors: “altho’ generally the mere mouths of their Constituents, they may be intentionally left sometimes to their own judgment, guided by further information.”

MacBride’s book disappeared without a trace, and in 1972 the champion of the faithless elector was chosen by the Virginia Republican Party as a Nixon-Agnew elector. It would seem that the fabled Nixon intelligence team, otherwise occupied at the Watergate, failed to do the necessary background check.

Meanwhile, at a much less pricey (if bug-less) hotel 2,000 miles westward–the Denver Radisson–the Libertarian Party was born. In that Watergate June of 1972, 100 devotees of laissez-faire–Ayn Rand readers, free marketeers disgusted by the Nixon administration’s imposition of wage and price controls, and congenital rebels–nominated for President John Hospers, an eminent philosopher from USC who once almost flunked a football-swift but classroom-slow jock named O.J. Simpson. “Humbled, dubious, and a bit frightened,” Hospers ran a thoughtful and low-key campaign; his name appeared on the ballot in just two states. When he told a colleague at USC that he was running for President, the impressed pedant replied, “President of the Faculty Council?”

But Hospers had a secret. Roger MacBride had phoned the philosopher to tell him that he intended to cast his electoral vote for Hospers and running mate Tonie Nathan, thus ensuring that the first woman to receive a vote in the Electoral College had no familial ties to organized crime.

The Hospers-Nathan ticket received just 3,673 votes, but the big surprise came one month after Election Day, when Vice President Spiro Agnew announced to a befuddled nation that one electoral vote had been cast for John Hospers of California, placing him just 16 electoral votes behind George McGovern.

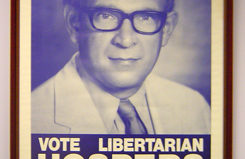

Roger MacBride’s faithlessness–or was it fealty to a higher principle?–earned him the Libertarian Party’s 1976 presidential nomination, but this time around there were no refractory libertarians lurking on the greensward of old Electoral College.

MacBride’s bolt invigorated the newborn Libertarian Party, and it taught the older parties a valuable lesson: When appointing electors, stick with hacks. And never choose a man who has written in praise of the faithless elector.