In December of 2016, I observed, alluding to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, that Twitter was akin to Trump’s ring of power. My point then was relatively straightforward: just as the one ring to rule them all in Tolkien’s fictional world had been devised to control all other rings of power, so Trump deployed Twitter to manage other forms of media, as, for example, when cable new stations or newspapers covered his tweets as newsworthy items or topics of editorial opinionating. With one tweet, Trump could own the news cycle.

In response to Matthew Stewart’s essay, I’d like to disassociate the analogy from Trump and develop it a bit further.

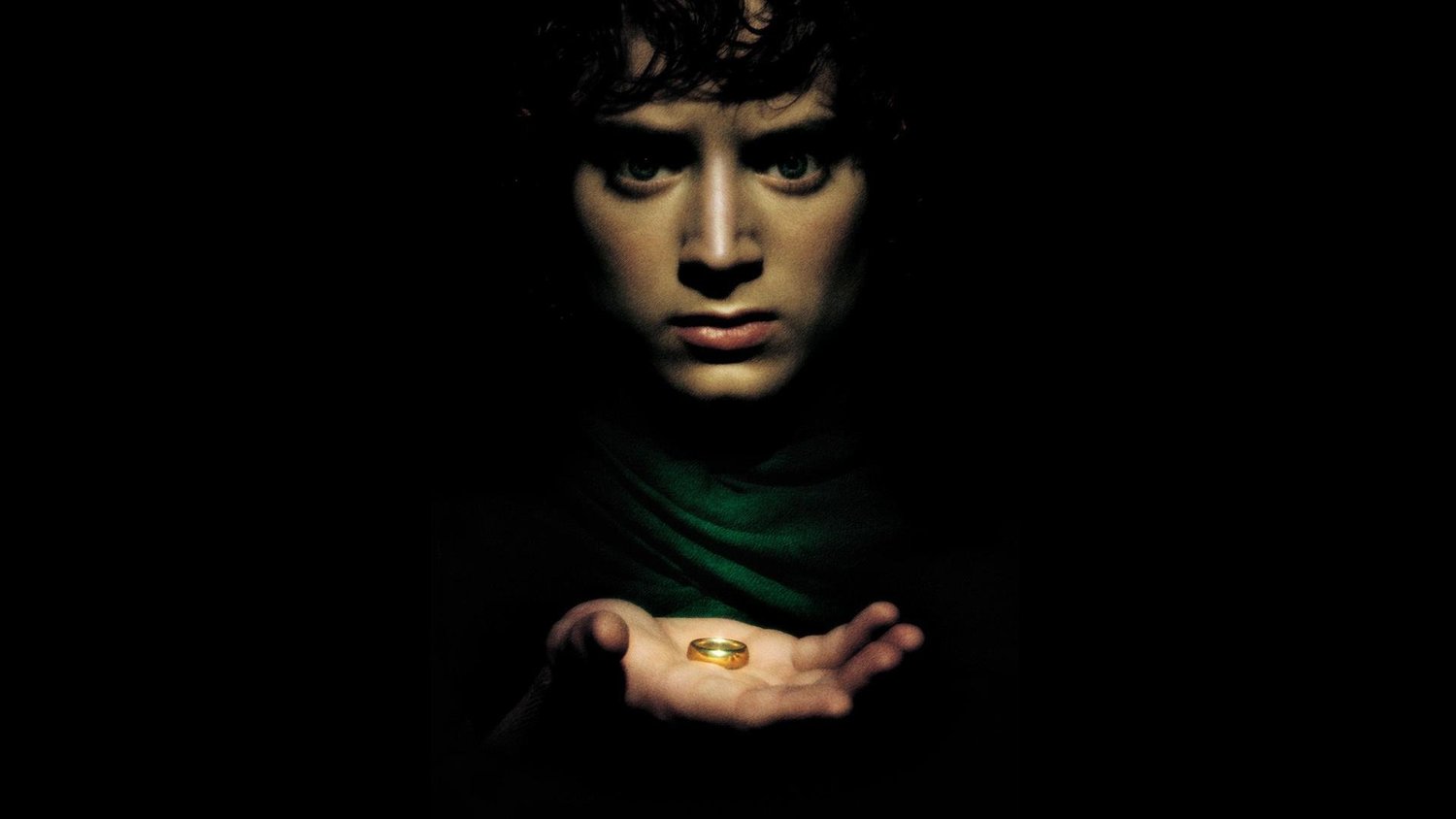

Twitter can indeed be a source of power, and, like all power, wielding it is a morally fraught business. In Tolkien’s world, the One Ring makes the wearer invisible to all of those around them but with a catch: it will make the wearer visible to Sauron, the forger and true master of the Ring. The power Twitter confers, on the other hand, is precisely the power to become visible, potentially to a great many people. The catch is that, for the vast majority of users, such visibility is ephemeral and superficial. It is gone in a flash and what it makes visible is not a human person in their depth and complexity but a reduction of the person distorted to fit the demands of the medium. Gollum is a fitting image of such a reduction.

In pursuit of attention for the self, we risk losing the very self for which we seek attention.

As others have observed, the dynamics of Twitter, and social media more broadly, are not unlike that of a slot machine: We chase attention like a gambler chases the jackpot, and, as with the gambler, the chase may very well turn us into the worst version of ourselves. In pursuit of wealth the gambler loses what wealth he has. In pursuit of attention for the self, we risk losing the very self for which we seek attention.

It is also true that Twitter’s temptations should appear especially malicious to anyone with localist sympathies. It can foster dissatisfaction with the constraints of place and time, and it tends to disorder our relationship to both. These are traits shared with social media more broadly, and, in many respects, with the internet as a whole. There is much more that can be said about the temptations posed by Twitter—its detrimental qualities and its unfortunate social and political consequences—but others have covered that ground already.

There are other interesting dimensions of Twitter use that a comparison to the ring of power elucidates. For example, as with the Ring of Power, it is often the case that the wisest among us, like Gandalf, refuse to bear it at all. I’d also suggest that those, like Boromir, who are most naively intent on using the power of the ring for good are also those who are most likely to be corrupted by its power.

Yet it is also the case with the ring of power that some were called upon to bear it for a time, Bilbo and Frodo most importantly but also, briefly, Samwise Gamgee. My point here is that, by analogy, it is hard to rule out altogether the possibility that some may be called to use Twitter (a concession that Eric Miller grants even in his support of Matthew Stewart). It is, finally, a matter of prudence and discretion, and a matter of conscience.

The language of bearing a burden and being called to do so when transferred by analogy to Twitter may seem silly, but I use it advisedly. I use this language because I do believe the use of social media can be profoundly formative, especially so if used naively. It is no mere tool that can be taken up in a simple and uncomplicatedly charitable manner by those who know what they are doing. I have no qualms about surrounding its use with morally charged vocabulary that foregrounds the consequences of it use.

It is not impossible to imagine using Twitter in a way that countermands its dominant tendencies.

I realize that reading this someone will point out, rightly, that Frodo took up the burden of bearing the ring only so that it might be destroyed. Fair enough. I’d suggest that while destroying Twitter, as gleefully satisfying as the prospect may appear, is not something to which any user can reasonably aspire, it is not impossible to imagine using Twitter in a way that countermands its dominant tendencies. At the council of Elrond, it is made clear that, if the Hobbits succeed, it will be because they are working against the logic of the ring and its maker. The quest to destroy the ring might succeed precisely because Sauron would never imagine that anyone would refuse the power the ring offered. Likewise, Twitter might be taken up by those who refuse the lure of visibility.

Now it is also worth noting, and this point is critical, that Bilbo and Frodo, both of whom bore the ring for extended periods of time, are not left unchanged by the ring. Humbly noble as they may have been, they were not beyond its corrupting influence. So it is with Twitter: there will be very few who are so virtuous, indeed so holy, as to take it up and be left unchanged. About this we should be clear-eyed.

Below are a handful of suggestions for using Twitter against the grain, as it were, to none of which, to his own detriment, the present author faithfully adheres.

- Refuse the ironic voice.

- Turn off notifications.

- Tweet sparingly.

- Periodically take a few days off at a time.

- Delete the app from your phone.

- Signed out should be your default status.

- Sign in only with clear intent, not to satisfy a craving for distraction or attention.

- Consider using the Twitter Demetricator to hide all metrics on the interface.