The coming of October, and of the World Series as culmination, invites reflection on yet another season in which the home run (and the strikeout) became the centerpiece of the baseball world at unprecedented levels. But perhaps it is better to reflect against the tide of launch angle and slugging percentage and ‘good strikeouts.’ In this regard, Paul Dickson’s new book about the master manager of small-ball, Leo Durocher, appears as a useful anachronism. Likewise, after last year’s World Series was marred by Yuli Gurriel’s racially-insensitive gesture and shout towards Yu Darvish, a long discourse on Durocher cannot avoid his perfection of the art of verbal baiting. But the question of racial insensitivity, so rife in this world and our nation, also throws an intriguing, illuminating glance back at Durocher, the ultimate old-school baseball man, because he was always frank and forward in his support of the integration of the game, and of his embrace, in the crucial build-up to the 1947 season, of Jackie Robinson’s arrival on the Dodgers. So perhaps Durocher is a foil, not only for the ways the game has progressed, but also the ways that it hasn’t.

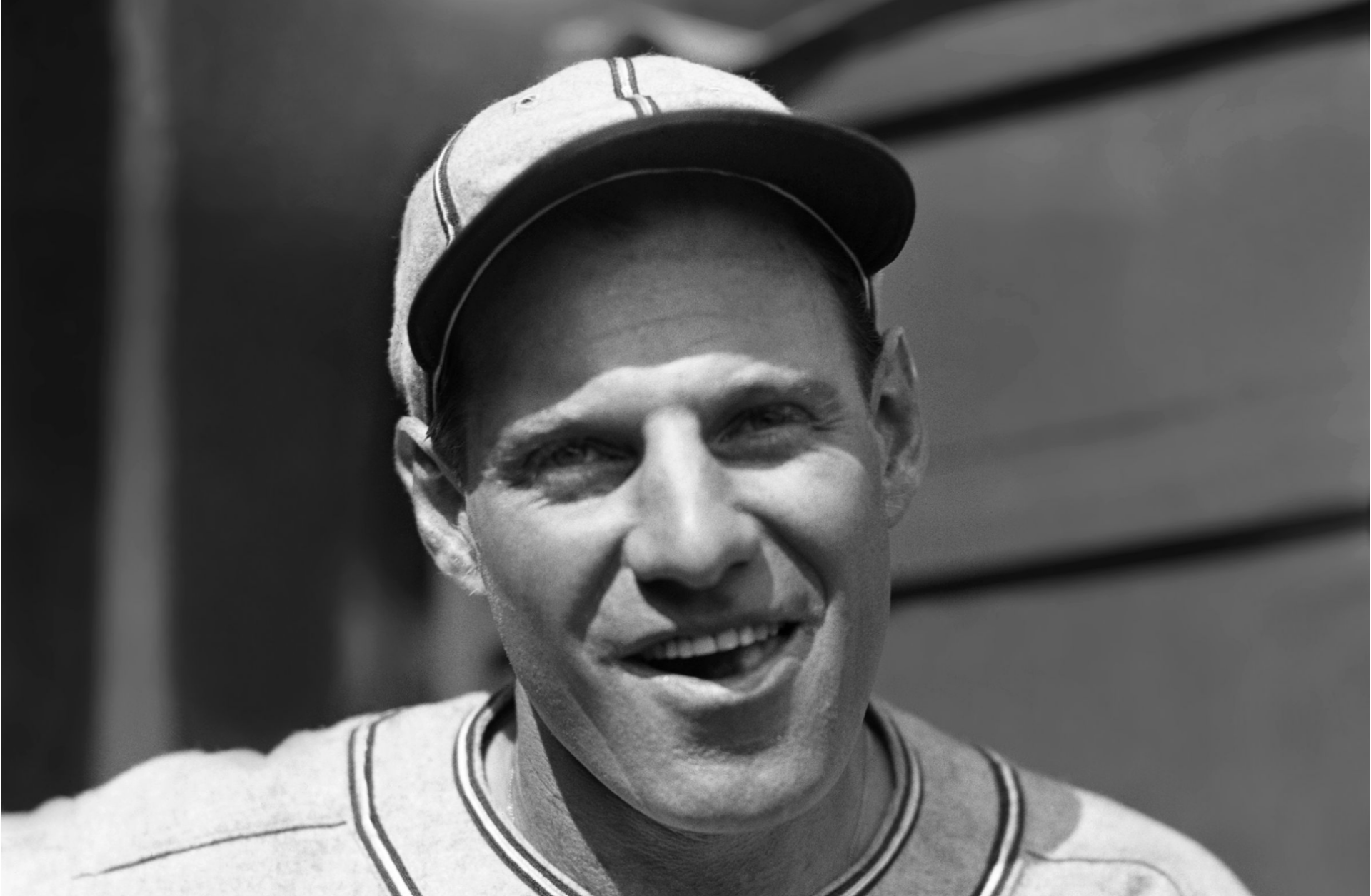

Dickson points out from start to finish the centrality of contradiction in Leo Durocher’s life, “the conflict between reality and stagecraft, drama and dramatics” as he posits in his introduction, “the dichotomy of Durocher,” as he states in the conclusion, quoting an obituary from Newsday. Dickson sets him up as the most hated man in baseball for nearly a half century, but also the most beloved, or at least the most well-known and talked about, a celebrity outside of baseball, beyond its abstruse confines, in a way that no other figure in the game, not even the Babe, was able to sustain. Along the way, Dickson uncovers a number of stirring surprises that surround Durocher.

Strangely, Babe Ruth was one of his first friends in baseball, and then one of his lasting enemies. Leo had risen through the summer of 1925 from an obscure factory league part-timer, to an Eastern League ‘weak bat, strong glove’ shortstop for the Hartford Senators, at the center of a media storm in New England ranging from laudatory to mocking, to an unexpected, unlikely signing by the Yankees (who were having a rare bad season) who needed defensive help up the middle, to an appearance on the Yankees bench as a starry-eyed call-up in the last few games of the season. The chief source of Leo’s encouragement on his meteoric rise that year was an African-American co-worker at the Wico factory in Springfield named David Redd, who admonished him, as Redd later recalled, “you’re a brilliant young fellow, and you’re a better ball player than all the others around here. You’re different.” Hence, in that first full season, many of the ingredients of Durocher’s mien were in place: scrapping against the odds, friendship across color barriers, both love and hate from the media and fans, and a strange penchant for landing in a fortuitous place.

Though Leo didn’t stick with the Yankees until the 1928 season, when he finally cracked the Murderer’s Row lineup based on his slick glove and strong arm, he immediately made his presence and personality felt with an Opening Day dust-up involving none other than the aged and surly Ty Cobb, finishing his career with the A’s. Durocher apparently obstructed Cobb on the basepath and then threw him out at third base, and later, at the behest of Babe Ruth, used the trigger epithet on Cobb—you guessed it, “penny-pincher”! Cobb threatened to dismast Leo, but the Babe came in and restrained the Georgia Peach until Durocher could bolt for the clubhouse. From day one, the pattern was struck for Leo—berating opponents no matter how venerated, pushing the rules to gain an advantage, and getting away with it more times than not.

Off the field, amidst the glitz and glam of Broadway, Leo also got away with a certain outlandishness—dressed to the nines, cavorting with actors and thinly-veiled gangsters in Prohibition Manhattan, and eventually getting his own “Leo Durocher Day” at Yankee Stadium in June, complete with a new $1,000 bill from ‘friends,’ even though he’d played in less than 50 games and was benched for weak hitting (Gehrig and Ruth, as Dickson points out, would each have to wait until he was dying to get such an honor). It was also during that rookie season that the press gave Durocher the nickname “Lippy,” which would live on as “Leo the Lip” and achieve immortality, over against the other contender from that year, proffered by Ruth himself: “The All-American Out.”

Yet, despite the tenuous life on the field and the decadent life off it, Durocher also found a mentor and model in Yankees skipper Miller Huggins, and while often on the bench, “he kept a small notebook in which he took notes on how Huggins managed the Yankees.” Indeed, Huggins protected and defended Durocher both on and off the field, so when a mysterious skin infection took the 51 year old manager’s life at the end of the 1929 season, Leo’s Yankee career was effectively over, especially with the persistent belief on the team that Durocher had stolen Babe Ruth’s watch, a story never confirmed. An off-season trade to the Reds put Leo into the National League and he would never leave the senior circuit; with Cincinnati he continued as a defensive whiz with a wild life in the casinos on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, with Reds owner Sidney Weil filling the role of patron/enabler. When baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis pressed Weil not to play Durocher until he paid his vast bills due all over New York, Weil intervened financially. And though Leo hit only .227 and .217 in the 1931-32 seasons, he “was deemed the best fielding shortstop in all the major leagues,” and “drew much attention by his ability to successfully play out of position,” apparently bringing to the National League the sort of shifting he saw in his Yankee days used against the Babe.

Because the Reds were atrocious, and the Cardinals shortstop accidentally shot himself in the foot in the off-season, but mainly because Durocher’s competitive fire was attractive to the Cardinals general manager, an early-season trade in 1933 brought Leo to the team that would forever be known as the “Gashouse Gang,” a band of wildmen who loved to win. Durocher fit right in, and the man who made the trade happen was none other than Branch Rickey, who would serve as his unlikely advocate for the next decade and a half of Leo’s rocky rise to fame. “The team was known for playing tough and dirty, and their weapon of choice was the beanball. Not only did they play rough, they also looked rough. As a team, they usually showed up at game time unshaven and dressed in uniforms still grimy from the previous game.” By the 1934 season, Durocher was named captain, and at the season’s end, he had his greatest achievement as a player, as the Cardinals beat the Tigers in seven games and Leo chipped in seven hits along with “bare-handed stops, over-the-shoulder catches, and acrobatics seldom seen before. Damon Runyon said the Series proved that Durocher was in a class by himself, calling him one of the greatest fielding shortstops of all time.”

But by 1937, Durocher had worn out his welcome (another recurrent theme in his biography) with Cardinals player-manager Frankie Frisch, so Branch Rickey continued his benevolence toward Leo by trading him away to the Dodgers, where he was likely to be groomed as a player-manager himself. And indeed, that is just what happened, but not before Leo had publically humiliated another of the Dodger coaches also angling for the skipper’s spot, his old frenemy Babe Ruth, who he pushed and slapped in a locker room incident that one eyewitness said was “as unthinkable as pulling a crutch out from under your grandfather”—but Leo was never one for reverence. By the end of the 1938 season, the Babe was fired by the Dodgers and Durocher named skipper. His legendary career as a manager began, appropriately enough, with the 1939 World’s Fair in full swing, the Dodgers signed on to a radio contract with WOR New York, and the first ever television broadcasts made from an August game at Ebbets field, with Durocher the featured interview. Coupled with the constant presence of movie star George Raft in his private box at the stadium, and Leo’s nightclub resume, the star power had arrived in Flatbush.

Leo’s Dodger years, from a baseball point of view, were dominated by the talent drain because of WWII, though he had very readily entered a somewhat different conversation about the talent pool of baseball as early as 1939, when “Lester Rodney, a sports reporter for the Communist Daily Worker, asked Durocher if he would sign Negro players if he had the chance. ‘Hell, yes!’ Durocher shot back, ‘I’d sign them in a minute if I got permission from the big shots.’ He then added: ‘I’ve seen plenty of colored boys who could make the grade in the majors. I have played against some colored boys on the coast who could play in any big league that ever existed.’” Despite his many run-ins with his own players and with irate fans, and hence with the criminal justice system, during his war-years managing, Leo retained the trust of the now-Dodgers GM Branch Rickey, who had signed Jackie Robinson to a minor league contract while Leo was on an Asian Theater USO tour with Danny Kaye after the 1945 season. As Dickson points out, despite his great reservations about Durocher’s personal behavior and choices, “Rickey understood intuitively and correctly that Durocher would fight for one of his own guys on the field, regardless of color, creed, or anything else extraneous to the winning of ballgames.”

That trust is well-placed, and Dickson shows not only the acerbic Durocher talking down a potential uprising among Dodger veterans against the inclusion of Robinson in spring training of 1947, but also a whole litany of moments throughout that winter and spring when Durocher explicitly spoke of his excitement about the coming of black ballplayers. In what was likely baseball’s, and maybe even American culture’s, critical turning point on race relations, Leo was openly leading the charge. Ironically, he never got to manage Jackie that first crucial season, because forces from above, as it turned out all the way from the Supreme Court and other spheres of influence, led Commissioner (and former U.S. Senator) Happy Chandler to suspend Durocher for the whole season, on thin and even contrived evidence, after Leo had followed the Commissioner’s direct command to stop all contact with Hollywood gamblers and gangsters. As it turned out, “in light of Durocher’s ban and the commotion surrounding it, Red Smith later called Robinson’s major league debut ‘a whisper in the whirlwind.’” Whatever the intention of the year-long ban, it created the sort of contradiction and reversal upon which Leo staked his life and career, and this time the effect was beneficent: “Time magazine may have had the last word when it said that Chandler had done the seemingly impossible, which was to turn Durocher into a sympathetic character.”

Upon his reinstatement the next year, Durocher reversed field again, going to battle with his mentor Branch Rickey, in this case about Leo’s desire to start Roy Campanella at catcher, thus integrating another position in baseball—and Rickey would not stand for it. At the same time, Leo was on the attack with criticism of Jackie Robinson, whom he was finally managing everyday, and with whom he sharply feuded. Dickson points out, with corroborative evidence from many sources, that neither Rickey nor Durocher was motivated by racial bias in these situations, but there were just too many strong-wills at work (including Jackie’s) in too small a space. And so the rollercoaster took another loop, as Rickey and Giants owner Horace Stoneham did the unthinkable—a mid-season swap of a manager from one rival to the other, as Durocher moved into the Polo Grounds to manage the Giants. To gauge the magnitude of the change, Dickson points out that “it was the first and only sports story ever to be recorded on the tape produced by the Dow Jones ticker.” But with a growing roster of young players, including Monte Irvin and eventually the teenaged Willie Mays signed from the Negro Leagues, and with his movie-star wife Laraine Day (a devout Mormon who neither drank nor swore, but who was willing to endure the scandal of a patchy divorce and remarriage for the love of the profane Durocher) now hosting the pre-game show on WPIX TV, Leo began to win the Giants faithful.

In 1951, all the charm, all the positive possibilities built into Durocher’s mercurial nature, all of the sharper’s tactics to win at all costs, coalesced in the greatest season in baseball history. Many people observed a kinder, gentler demeanor from the manager: “One common theory was that Durocher was turning into a nice guy because of the influence of Laraine Day; another was that he realized Willie Mays and some of his other young players could not flourish under the old Leo.” As harsh and hectoring as Durocher had been to Jackie (who was almost 30 years old at the time, a grown man with his own strong personality), he was extraordinarily fatherly and longsuffering with Willie (who was less than a year out of high school when he was called up). As a former vendor for the Giants in the early 1950’s attested: “’Durocher and Mays brought an excitement to the Polo Grounds that has never been duplicated in any other ball park since. It was a special time.’” The Giants came back on the Dodgers from thirteen games down in mid-August, won 37 of their last 44, tied their cross-town nemesis on the final day of the season, then won the three-game playoff on Bobby Thomsen’s “shot heard round the world,” the most famous homerun ever hit—though Dickson garners fairly clear evidence that Leo had inveigled a system of spying catcher’s signs through telescope and signals, thus tainting forever the moment, or at least ramifying his famed willingness to ‘trip his own mother’ to win a game. Though they lost to the Yankees in the World Series (Durocher had started Hank Thompson in the outfield in Game One, where he joined Mays and Irvin as baseball’s first all-black outfield), the magic of the season was palpable: “The 1951 season was Durocher’s masterpiece. ‘Durocher was an inspired manager that year,’ said Monte Irvin. ‘He kept making the most astounding moves and seeing them pay off. Things like the right pinch hitter at the right time, the right pitching change at the right time, moving his fielders around. It seemed that over the last few months of the season he just couldn’t make a wrong move.’”

And then, after a few off years with Mays in the army, an even greater season was in store for Durocher and the Giants in 1954, even as a cabal of owners apparently, according to an article in Confidential magazine, “were still furious with Durocher for his role in integrating the Dodgers and Giants and then conspicuously bringing up—and making stars of—other black players.” Nothing stopped Leo in 1954, though—even his role players learned to platoon, and he could do no wrong with Dusty Rhodes, “a man who Durocher explained couldn’t run, couldn’t throw, and couldn’t field, but was an extraordinary hitter, especially as a pinch hitter.” As a boon, Leo’s color-blindness towards his players rubbed off on Mays and Rhodes: “Rhodes was a free-spirited Alabaman who regarded the black players and was regarded by them as, to use Mays’s term, a brother.” The Giants swept the Indians in the World Series, famously enabled in Game One by ‘the Catch,’ Willie Mays seeing-eye grab 450 feet from home, and the awesome throw that followed it to hold the runners—as Dickson well phrases it, “the most famous defensive play in baseball history”—and Dusty Rhodes’s pop-fly 260 foot homerun to right at the oblong Polo Grounds. Leo was on top of the world, and almost immediately, as Dickson limns the pattern of that quirky world, things began to fall asunder.

Leaving the Giants after a contentious 1955 season (by the way, the year that Brooklyn finally won it all, powered by Robinson, Campanella, and a few of the other players Durocher had originally lobbied for), Leo stepped into a career with NBC, and this man so at home on radio comedies and USO shows in the 1940’s proved a horrible flop hosting his own comedy show: “Durocher was colorless, cold, and widely derided for chewing gum in front of the camera.” He was better at securing talent for the network from his A-list celebrity friends, but he was basically out of work until he caught on with the now Los Angeles Dodgers as an assistant coach in the early 1960’s, allowing him to guest star more successfully as ‘himself’ on shows like “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “The Munsters,” and “Mr. Ed.” But his criticism of Dodger manager Walter Alston was ill-received (Alston managed the team to a sweep of the Yankees in 1963), and he eventually left to take the rather lackluster job as Cubs’s manager, starting in 1966. As he had back in Brooklyn with Robinson, Leo clashed in Chicago with the team’s most popular player, Ernie Banks. In both cases, Dickson argues, the source was not racial bigotry but rather stubbornness and envy, though in the case of the easy-going Banks, the response to Leo’s criticism was always a kind and compliant word, as he continued to perform at a high level into his late thirties.

In the 1969 season, the Cubs appeared to peak under Durocher’s chafing motivations, and seemed destined to take the National League East crown, when Leo inexplicably went AWOL from the team a few times down the stretch, while also refusing to rest any of his starters. His managerial and leadership gaffes seem to have played as much a role in the Cubs’ meltdown (and the emergence of the Miracle Mets), as his brilliance had led to the Giants’ success 15 years earlier. Leo had lost the magic, and Dickson documents the decline with a brutal thoroughness—case in point, Fergie Jenkins’s later statement: “’If a man had a slight injury or was just plain tired Leo did not want to hear about it. Leo just rubbed the man’s nose in the dirt and sent him back out there. You played until you dropped.’” Things got even uglier in the next few seasons in Chicago, with pitcher Ken Holtzman claiming that Leo called him a ‘kike’ and berated him for not playing on Jewish holidays. So the cultural sensitivity only went so far. Likewise, in the 1972 season, Durocher was roughed up in the media for his harshness towards young fans seeking his autograph, and for his belittling of the Players’ Association during the 1972 strike. Just as he had done in 1948, Leo skipped from one NL team to another mid-season (though this time after being fired by the Cubs), and he ended up, in all places, in Houston, at the Astrodome that he had roundly mocked. A season later, he realized the game had changed beyond his capacity to adjust, and he resigned at the end of the 1973 season in Houston, stating, “I understand it’s a different era, I learned that players do what they please nine times out of ten. It’s a different breed.”

Leo had miraculously become irrelevant, and though his revisionist, ghost-written autobiography Nice Guys Finish Last (which Dickson points out was never actually a quote of Durocher’s) tried to resurrect the fiery, glossy image, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, the only news on Leo was the yearly snubbing by the Baseball Hall of Fame, where several of his old enemies wielded power on the Veteran’s Committee. The contradictory nature of his whole career was concentrated in these rancorous yearly votes, though Leo, living out a playboy retirement in Palm Springs with Frank Sinatra as his neighbor, rarely raised his voice in acerbic protest. When, however, a year before his death in 1991, he was asked about a rumor that he’d been banned in 1947 for fixing the 1946 NL playoff between his Dodgers and the Cardinals, the old lion was roused one last time, and his profanity laced denial showed a glimpse of the fiery old soul (Dickson offers a lengthy footnote showing the implausibility of those accusations).

When Leo passed away at last in October of 1991, the world of baseball seemed wracked with guilt at having left him out of the Hall. Willie Mays wept as he eulogized the man who had been so kind to him, saying, “All I can say is that I have lost a dear father.” By the time he was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1994, the final irony, the final contradiction, the final mingling of charm and viscera, circled round, as his ex-wife and induction speaker Laraine Day claimed that “Leo’s public savagery was self-created. ‘He was a very generous, kind, thoughtful person who put on a great show,’ Day said.” And so he did, because no one is quite sure how to measure the man, as villain or hero, and perhaps that is his greatest achievement, that sustaining of the “combative, swash-buckling style” as listed on his Cooperstown plaque. The sort of darkly beautiful, melodramatic epitaph that Leo would perhaps have loved.