Fifty years ago today, Thomas Merton died suddenly during a visit to Thailand. During the past few months, I’ve been thinking about the ways his life and writings speak both to the famous events of that tumultous year and to the polarized politics of our own time. When a group of Porchers gathered this September to reflect on the enduring relevance of the events of 1968, we discussed some of the well-known protests and riots that took place that year. But Thomas Merton didn’t come up. Perhaps his unexpected death in December of that year was overshadowed by more headline-grabbing events. Nonetheless, Merton’s commitment to a contemplative politics has much to teach us about how to live and act in a time when politics seems to be reduced to shrill voices one-upping each other on Twitter and TV.

For Merton, pursuing a contemplative life and pursuing justice were inseparable.

Merton did not just write about the difficulties and joys of his monastic vocation; he also had much to say about how to stand effectively against unjust social structures. Indeed, for Merton, pursuing a contemplative life and pursuing justice were inseparable. As Henri Nouwen claims, “the great power of Merton as a writer still remains in his ability to comment on the concrete happenings of the day, and to do this out of a contemplative silence.” Nouwen goes on to articulate how Merton’s vision was profoundly shaped by his life of prayer: “Prayer makes men contemplative and attentive. In place of manipulating, the man who prays stands receptive before the world. He no longer grabs but caresses, he no longer bites, but kisses, he no longer examines but admires. To this man, as for Merton, nature can show itself completely renewed. Instead of an obstacle, it becomes a way; instead of an invulnerable shield, it becomes a veil which gives a preview of unknown horizons.” This receptive stance enabled Merton to see beyond zero-sum conflicts and imagine opportunities for genuine reconciliation and renewal.

Merton’s contemplative stance leads to a deep recognition of his own responsibility for and complicity in the systemic injustice of his society. What he writes in 1941 about Hitler is true also of Trump:

When I pray for peace I pray for the following miracle. That God move all men to pray and do penance and recognize each one his own great guilt, because we are all guilty… we are a tree, of which Hitler is one of the fruits, and we all nourish him, and he thrives most of all on our hatred and condemnation of him, when that condemnation disregards our own guilt, and piles the responsibility for everything upon somebody else’s sins!

Our current president is one of the fruits of our enmeshment in what Neil Postman refers to as the “peek-a-boo” world generated by the political-entertainment industry. “It is a world,” Postman writes, “without much coherence or sense; a world that does not ask us, indeed does not permit us to do anything; a world that is, like the child’s game of peek-a-boo, entirely self-contained. But like peek-a-boo, it is also endlessly entertaining.” Merton’s bracing prayer for peace implies that insofar as we are entertained by this game of peek-a-boo, we are guilty.

In My Argument with the Gestapo, Merton imagines himself visiting England at the outbreak of World War II. At one point, Merton (signified by “M”) has this conversation with another character:

B: I stay up all night, I hang on to the walls and the explosions of bombs break my back in half, I live in black smoke of this city’s burning, and the dust of the ruins is always in my throat. I don’t want to know that nobody’s responsible. I want to know that one man is. I haven’t time to know anything less arbitrary than that. Tomorrow I may be dead.

M: What difference will it make, then, what political fact you happen to have known?

B: I want to know who is responsible.

M: Even if it isn’t really true?

B: In the simple sense in which I want to know it, it will be true enough for me: I will have been killed by one of their bombers, and the symbol on the rudder will be enough for a judgment.

M: You want to die, perfectly sure of who it is you hate?

B: Yes, why not? At least it is something definite to die with.

M: Not definite enough for me, and not the kind of definiteness I want. I want to die knowing something besides double-talk.

B: There is no such thing as double-talk, not to me, there isn’t. Not any more.

B: (a little later) Is that what you are here to find out? Your part in what is happening? Do you want to know how much you yourself are responsible for?

M: You guessed it.

This conversation weaves together features of our contemporary political discourse—a sort of “post-truth” posture, an insistence on identifying (and destroying) villains, a desire for clear boundary lines delineating who is right and who is wrong. Yet Merton’s contemplative politics resists these temptations by grounding any action in a recognition of “how much you yourself are responsible for.” And his questions finally lead his interlocutor to silence and self-reflection. Somehow, we have to bring each other to the point of silence—our conversations have to include “(a little later).”

Such conversations work to clear the ground of the double-talk that so often infects protest politics and mass movements. (One of Merton’s most perceptive methods of doing this, I think, was through his “anti-poetry.”) Merton’s probing questions invite us to move past the simplistic logic of movements, a logic that pushes those who disagree with us to “the wrong side of history” while planting ourselves safely on “the right side.”

This perspective informs Merton’s 1966 book, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, in which he warns against “total involvement in the intricacies of a movement.” No matter how commendable a movement might be, the logic of movements is a logic that casts blame on others rather than recognizing the ways in which, as Wendell Berry puts it, we are “involved inescapably in … wrongs that [we] oppose.”

Berry articulates his critique of movements most clearly in his essay “Think Little.” Berry warns that protest politics too often mirror that which they abhor, so he recommends rooting political action in radical personal change. For instance, he recommends growing a garden as a way of practicing our commitment to caring for the earth. If our politics stops with such private practices, it is inadequate, but if it does not grow out of private practices, it is liable to be warped and damaging. As Berry explains, when “we apply our minds directly and competently to the needs of the earth, then we will have begun to make fundamental and necessary changes in our minds.” This is so because “a person who undertakes to grow a garden at home, by practices that will preserve rather than exploit the economy of the soil, has set his mind decisively against what is wrong with us.

A contemplative politics is not a quietist politics.

A contemplative politics, then, is not a quietist politics. Merton was very supportive of the Civil Rights movement, and Berry has been arrested for his protests against strip mining. But a contemplative politics seeks to avoid the weaknesses of fads, of flash-in-the-pan movements, of protest performed on Twitter and Instagram. While the digital tools of modern politics can be powerful, they tend to foment excitement rather than creating lasting change. The subtitle of Zeynep Tufekci’s recent book accurately captures this paradox: Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest.

Merton, however, points to a different mode of politics, one as needed now as it was in the 1960s. As he writes in “Rain and the Rhinoceros,”

The contemplative life . . . must not be construed as an escape from time and matter, from social responsibility and from the life of sense, but rather, as an advance into solitude and the desert, a confrontation with poverty and the void, a renunciation of the empirical self, in the presence of death, and nothingness, in order to overcome the ignorance and error that spring from the fear of “being nothing.” The man who dares to be alone can come to see that the “emptiness” and “uselessness” which the collective mind fears and condemns are necessary conditions for the encounter with truth.

For Merton, the root of authentic protest, of healing politics, is contemplation and prayer. For Berry, it may be growing a garden. Such actions can seem utterly incommensurate with the problems we face, but they also may be forms of protest that actually embody a more peaceful and just way of life. Frenzied calls for action and change too often simply mirror the violence or injustice they claim to oppose. In an age in which it seems everyone is trying to change the world with 240-character tweets, why not be really original and spend time praying or cultivating a garden? Though promises to pray certainly can be a kind of quietist withdrawal from necessary action, Merton’s example demonstrates that they may also be precisely what we most desperately need.

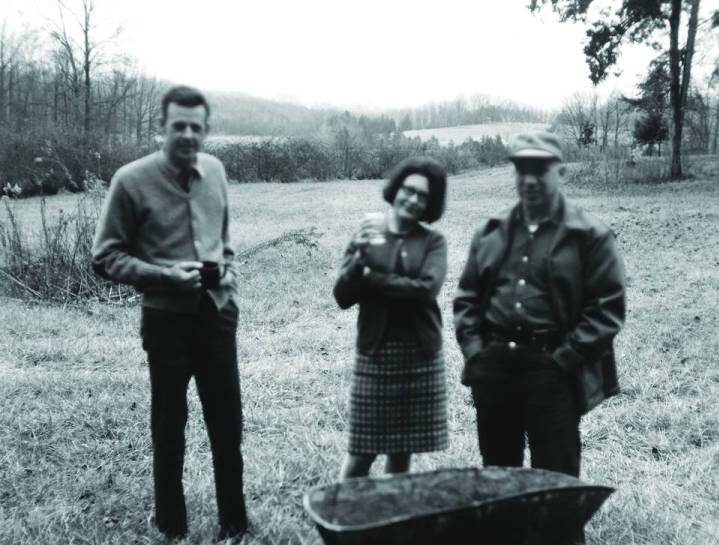

The header photo, by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, is of Wendell Berry, Denise Levertov, and Thomas Merton.

“What he writes in 1941 about Hitler is true also of Trump”

Sigh. There’s a shortage of sane sites on the internet. Please don’t push this one off the list.

I couldn’t agree more. I think that Hitler comparison could just as easily be applied to all politicians if one wanted to go that route.

I would just note that Merton’s prayer is not an indictment of Hitler but rather of those whose hatred and condemnation of Hitler blinds them to their own guilt.

You made the deliberately provocative choice to compare Hitler to Trump in your own words. You could have said “What he writes in 1941 is true also today” or something similar. To me it ruins the whole piece. Comparing any contemporary politician to Hitler would be just as valid, and just as absurd and off-putting.

United States has never seen an ugly demagogue the likes of Mr. Trump just as Germany had never seen as ugly a demagogue the likes of Herr Hitler. There you go, pedantics.

Great essay. After the 2016 election, I remember advocating to people that cultural change starts with personal change, and that if we want to see a slower and more peaceful world, then we need to live slower and more peaceful lives. Virtually everyone in the bourgeois liberal cohort I say this to condemns this opinion, doubling down on the idea that they need to instead be leading lives of ever more performative activism. It’s wearying. “Rain and the Rhinoceros” is such a wonderful little essay, and seems incredibly appropriate to cite here. What was that notion of Pascal’s? That all of man’s problems stem from an inability to sit in a silent room by himself? And yet to read deeply (or even shallowly, I guess) in Merton is to glimpse that the silent self is actually the ideal starting point for virtually everything. Getting caught up in the movement of the moment seems wildly misguided.

Thanks for this timely reflection. It’s timely for me personally, as I’ve just started reading Merton after having a passing introduction to him some dozen years ago in graduate school. I certainly appreciate his perspective more now than I did then. (Perhaps having five kids in the house makes the Trappist life seem a little more attractive than it once did.) Now I shall go and look up the books and essays of Merton that you so kindly referred me to.

Thanks Steve. If I were to recommend one Merton essay for your perusal, it would be “Rain and the Rhinoceros.”

Comments are closed.