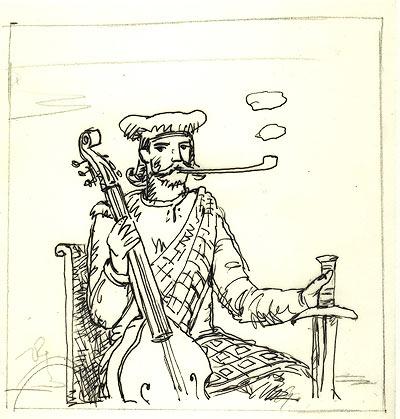

Among the legion of unjustly forgotten historical figures there’s an eccentric soldier and failed composer named Captain Tobias Hume. Unless you play the viola da gamba or you’re fond of Polish novelist Jerzy Pietrkiewicz—his Loot and Loyalty features Hume as its hero—you’ve probably never heard of this seventeenth century flop.

I know Hume only for an anonymous poem he set to music called “Tobacco,” or better known (if known at all) as “Tobacco is Like Love.” A music student tipped me off to this comic masterpiece in college, and, ever since, I’ve had at my command Captain Hume’s peculiar tune and the anonymous poet’s lyrics: “Tobacco, tobacco. Sing sweetly for Tobacco. Tobacco is like love. O love it. For you see, I will prove it.”

The poet proves it by way of simile: “Love makes men sail from shore to shore. So doth Tobacco.” Or: “Tis fond love often makes men poor” and “So doth Tobacco.”

A joke, sure—but every good joke contains an element of truth. Like tobacco, love renders victims helpless. It’s why love is depicted throughout literature as a disease in need of a cure—like Chaucer’s Black Knight in The Book of Duchess: “This is my pain, all remedy fled …” Or Romeo’s death: “O true apothecary, thy drugs are quick. Thus with a kiss I die.” Mark Twain distilled it when he called true love “the only heart disease that is best left to run on.”

One might argue that love is universally encouraged, while tobacco is universally detested. But love, like tobacco, is covered in warning labels. Read of Troilus and Cressida or Tristan and Isolde, hear from children of divorce, then insist everyone should fall in love. Even Australia’s extremely graphic cigarette warning labels have their counterpart in American health classes—where students are subjected to images of sexually transmitted disease.

On the other hand, for every health fascist there’s a cigar-chomping poet somewhere declaring: “tobacco is like love.” This applied literally to King James I—Hume’s “Tobacco” appeared a year after the king’s “A Counterblaste to Tobacco.” For Adolf Hitler, it was Winston Churchill, whose ever-lit cigar contrasted perfectly with Hitler’s racist anti-tobacco movement. However, the cigar was also a symbol of Churchill’s personal ambition—which manifested as vain delusion (even madness) in his worst moments, and as nobility and courage in his best.

You’ll find the cigar’s relationship to ambition in theologian Michael P. Foley’s old essay “Tobacco and The Soul.” The three forms of smoking, Foley argues, corresponds with Plato’s three-part division of the soul: The appetitive, spirited, and rational.

Cigarettes—fully and internally consumed (or inhaled) for instant gratification, then discarded—match with the appetitive. Hence the chain-smoker and the post-coital cigarette.

On the other end of the spectrum is pipe smoking, which Foley matches with the rational. As Foley points out, the pipe outlives the smoke session the way a philosopher’s questions outlive fleeting physical desires. Moreover, “like good philosophy,” says Foley, the pipe’s “sweet fragrance … is a blessing to all who are near.” Fittingly, literary sages like Gandalf chomp on the stem as opposed to the leaf.

If cigarettes make a haze, cigars make clouds. Visually impressive and eminently popular among honor-seekers like Churchill, cigars “bear public witness to the smoker’s prominence, his virility.” Puffed, not inhaled, the cigar’s “great billows of smoke” have “a greater impact on the spectator than on the smoker.” Cigars, then, match with the spirited part of the soul—where ambition is born.

In Plato’s view, when the spirited aligns with the appetitive, ambition manifests as the brashness to pursue deadly vices like wrath, lust, and greed. When the spirited aligns with the rational however, ambition manifests as the courage to pursue goodness and virtue.

As Churchill demonstrated, ambition can become obsession, or madness. Knowing what we know, you’d have to be mad to touch tobacco. Then again, you’d have to be a little mad to stand up to Hitler or fall in love. The spirited part of the soul—that potential source of madness—is where the hero finds the courage not only to slay the serpent, but also to pursue the virtues necessary to keep the girl—virtues like fidelity.

As the West replaces fidelity with promiscuity, courage with comfort, and the pursuit of virtue with instant gratification and infinite amusement, we should be doing more to rouse the spirited portion, not less. A heavy dose of eros and a strong cigar is at least one way of going about it, and the combination is also a pretty decent antidote to our brave new world.

Fortunately for the less spirited among us, there’s really no choice in the former. Eros and his Roman counterpart, Cupid, are known to shoot first and ask questions later. Regarding the latter—tobacco, like love, is a dangerous venture. While both may edify—“Love still dries up the wanton humor. So doth Tobacco”—they can also divide: “Love often sets men by the ears. So doth Tobacco.” Due to the dangers they pose, you’re a fool to push love or tobacco on anyone. Nevertheless, to every spiritless ascetic overflowing with pity for the love-struck and addicted, I should point out that the feeling is mutual.

Citing poetry like Hume’s tends to provoke the health fascists—and, unfortunately, every good and faithful Southern Baptist—but as the poem goes: “Love makes men scorn all coward fears,” and, well: “So doth tobacco.” This unfashionable truth is corroborated by lovers and smokers alike.

I’ open my humidor and withdraw an Arturo Fuente, salud!

Comments are closed.