As someone who appreciates the value of place, rootedness, and limitations on my horizon of vision, I’m afflicted with deep sense of unease as to the nature of my own time and place. Anthony Esolen’s new book Nostalgia provides much food for thought on this subject, and he does so without assuming that the past was rosier than it actually was. Thinkers from St. Augustine in late antiquity to Philip Rieff in recent times have made similar arguments, but this in no way detracts from the value of these similar musings. Esolen has an inimitable way with words, and these words comprise a rallying cry for those of us who have considered and found wanting the current milieu of autonomous desire. The more people who say this in print, the better.

What we long for, Esolen thinks, is home, and to do that, we must rediscover how to be pilgrims. So Nostalgia both begins and ends with the figure of Odysseus. Odysseus longs for home, not because home is utopia, but simply because it is, well, Home. Home, for Esolen, is sacramental. We want home, not because it is or ever could be heaven, but because the act of wanting and having one is an outward, earthly sign of a final heavenly home towards which we are on pilgrimage. Esolen is careful to avoid the Whig trap. No one time period is the pinnacle of creation. This absolves him from the need to find an actual example of the “good old days,” which, as any historian knows, were rarely as good as we think. So, this book can be usefully read as a philosophy of history, in addition to its commentary on our contemporary pathologies.

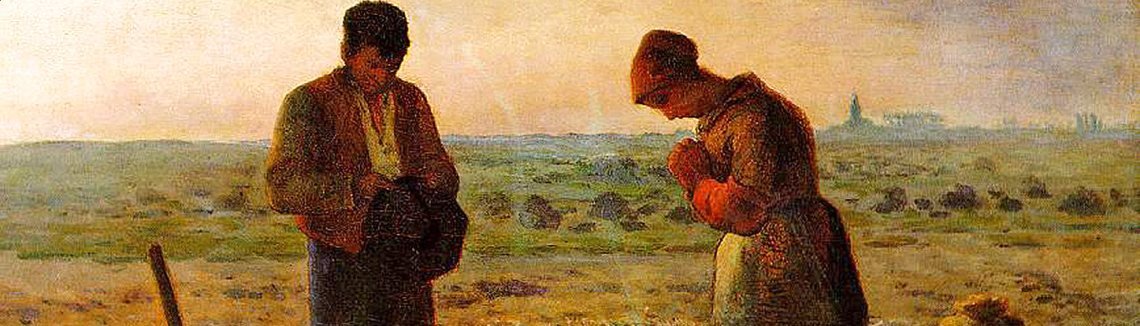

What kinds of things make home, Home, then? For Esolen, home exudes a sense of permanence. It is where the family lives, with its permanent covenant between man and woman. It is where the baseball field is or perhaps was, given the statistical likelihood that Progress will have decreed on the 8thDay: “let there be office blocks.” It is the vantage point from which we look back—like the subjects of Millet’s Angelus (1857-1859)—and see how our rootedness in place and time here on earth allows us to grasp the journey of faith which transcends this corporal existence (57-58).

Our places do not have to be beautiful in order to be sacred. In a particularly affecting section, Esolen describes the landscape of his boyhood, which contained the leavings from coal mines and railroad construction. The point? Places can be home without being necessarily “picturesque” (27-29). With the former, we remember where we come from, which tells us something about where we pilgrims are headed. With the latter, we selfie-consciously engage in “making memories” that amount to “pseudo-events,” in Daniel Boorstin’s apt phrase in The Image. So the difference between a “thing” and a “place” is that real people can think of place as sacred, and particularly, that these places have space for the messiness of the children who will look back on the homes we helped make for them. Weedy vacant lots may lack the antiseptic feel of glass skyscrapers, but baseball and children have little place in the latter (38-39).

Establishing that a time and place—along with their weeds—can be home without being perfect is not to say that all eras are equally imperfect. Esolen remembers smut on pool-hall walls long before smut on the internet (194). However, arguments abound that our era is more imperfect than many others, and here, Esolen can be usefully read in conjunction with the late sociological theorist Philip Rieff. Rieff argued that culture is the social means by which we travel the vertical line between everyday life and the transcendent demands of sacred order. Beginning in the 1960s and concluding with his posthumously published books, Rieff argued that we live not in a culture but in an anti-culture. Rieff justified this formulation with the argument that the modern West is the first culture in history to solve the problem of living up to the demands of the sacred by denying the very category of sacrality as such. Esolen carries forward this basic view when he argues that culture is the medium in which “man makes his dwelling in time and beyond time” (13), and in the overall argument that “nostalgia” rightly understood is a commitment to resuming the journey upward.

This brings me to Esolen’s central criticism of our era: we have, he contends, traded being pilgrims intent on a clear destination in exchange for a life of aimless wandering; we are merely bodies in motion and we call it “freedom.” Rieff once cast Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) as a visual depiction of our pursuit of un-limitedness. Klee’s angel, Rieff argued, could be anything we want, and so, “If one is feeling too definitive, too fixed, the best thing to do would be to take a bath in the river that is not the same river twice.” Esolen similarly invokes Heraclitus, warning against the idolization of change for its own sake, which can only lead (as Rieff also recognized) to defining the good as perpetual boredom-avoidance (70), or as Rieff earlier put it, modern man’s answer to the question “what for?” is “more.”

City of God is a second essential companion to Nostalgia. In memorable polemical style, St. Augustine similarly argued that the Romans of his day cared only to avoid boredom through the pursuit of pleasure:

they say; only let it flourish with abundant treasures, glorious in victory or–which is better–secure in peace, and what do we care? What is of more concern to us is that a man’s wealth should be always increasing for the support of his daily pleasure, and that the stronger may thereby be able to subject weaker men to themselves. Let the poor serve the rich because of their abundance, and let them enjoy under their patronage a senseless idleness; and let the rich abuse the poor as their clients and the appendages of their pride. Let the poor applaud, not those who take counsel for their welfare, but those who are most lavish with pleasures. Let nothing unpleasant be required; let no impurity be forbidden…Let the laws take cognisance rather of the harm done by a man to his neighbor’s vineyard than of that which he does to his own life. Let no one be brought to judgment unless he harms another’s property or house or health or is troublesome or offensive to someone against his will. Otherwise, let everyone do as he wishes with what is his, either with his own cronies or with anyone else who is willing…let sumptuous feasts be attended, where anyone who wishes and is able may play, drink, vomit and dissipate day and night. Let the noise of dancing be heard everywhere, and let the theaters boil with cries of dishonourable rejoicing and all kinds of the most cruel and wicked pleasure. If anyone disapproves if this happiness, let him be a public enemy. If anyone attempts to change or abolish it, let the abandoned multitude deny him a hearing, expel him from the assemblies, and remove him from among the living. Let those who procure this state of things for the people and preserve it when they have it be treated as gods. Let them be worshipped as they desire; let them demand whatever games they wish; let them hold them with, or at the expense of, their worshippers. Only let them ensure that such happiness is not assailed by enemy, pestilence, or any calamity.

Esolen is equally and refreshingly blunt, arguing that change—undirected by any sacred telos and controlled only by the individual—“goes in our time by the question-begging name of progress” (74). One of Esolen’s best examples of this “Static Idol of Change” is his description of progress as defined by our anti-culture:

heaven on earth is this: endless technological progress, giving us more and more sophisticated machines for the elimination of labor and the procurement of pleasures; more and more autonomy for the individual in sexual matters, paid for by more and more state surveillance of borders, skins, membranes, institutions that claim our fidelity and separate town from town, clan from clan, congregation from congregation… If that is so, then progress is the progressive dissolution of what it means to be human (77).

This “heaven on earth” bears suspicious resemblance to Satan in the bottom of Dante’s Hell, whose endlessly beating wings freeze the ice of his own imprisonment. As a translator of Dante, Esolen uses this image to good effect (77).

What is the result of this progressive dehumanization? Esolen argues that in matters of sexuality, “the desire to be ‘in control’ of what you do down under is like a mechanistic and merely chemical view of agriculture. It is to marriage what agribusiness is to tilling the fields. Nor does it matter that you are the one in charge of your own denuding” (21). Autonomy, n. A disappointing god, which amounts to a license “to be sterile in your prime and to die at will in your old age” (143).

Ultimately, I think, Esolen’s book is a bracing call to envision a home—a Place—as sacred in itself and as a symbol of that which is ultimately Sacred. Only with a vision of something enduring, something set apart, a transcendent goal, can our earthly pilgrimage make nostalgia meaningful. This is a worthy call, whether I have fond memories of my own childhood or not. In the early 5thcentury, Augustine asked us to give up our ceaseless and aimless pursuit of pleasure. In 1966, Philip Rieff was skeptical of Freud’s call to cease looking upward and adopt the “superior wisdom of choosing the second best.” Here in 2019, Esolen continues this line of thinking, inviting us to join him on a pilgrimage toward Home.

Sign me up.

Thanks for the fine article, Dr. Weinacht. I’ve been enjoying Dr. Esolen for years. I used his “10 Ways to Destroy…” as the basis for a project I implemented in one of my humanities courses. I aimed to cross it with Lewis’ characters from the Narnia series; most of whom serve as anti-examples of the dehumanizing trends Esolen brings to light.

Ok, so a couple or three things. This is well written and thank you. 2, well, forget that one. 3, my understanding of Reiff is that he is a Freudian, in that his critique is based upon an understanding of the structure of human consciousness being comprised of the id, ego and superego. The transcendent is important for the formation of the super ego; loss of the sacred means a society of the ego and id. Trump comes to my mind. Twitter.

Which, following my understanding, might lead one to make some missteps. Robert Wright authored a book called Why Buddhism is True. One of the things he writes about is more recent findings in neuroscience that may shed more light on the actual structure of our consciousness.

A prominent feature there is the – oh, what do they call it- illusion of a self. When thinking about these things what comes to mind isn’t the rightness of Buddhism but kenotic Christianity, or Eckhart or the Cloud of Unknowing.

Anyway, reason for all this is that sometimes I think that what’s required here is some sort of leap into a more faithful, more integrated, more human self. That the way is ahead of us, not behind us, and that it embodies a vision of our better natures.

But you know, maybe I don’t understand Reiff.

Dave:

I think that that view of Rieff has some plausibility, if you just stick with “Moses and Monotheism” and “Triumph of the Therapeutic.” In his final three books, though, you can see Rieff workings towards a description of what he calls “Fourth Culture,” and there, I think you’d find a more forward-looking vision. (If I understood your comment correctly.)

I don’t how Rieff would describe his intellectual evolution, were he still alive. But, to me, his later works have a much different feel than his earlier ones. I think it was in “Deathworks” where he mentions that when listening to Bach, he felt himself to be an “honorary Christian.” His critique of “third culture” gets even more savage in “Deathworks” and “Crisis of the Officer Class,” but, I think he’s still a bit more forward-looking there than in the earlier stage of his career. I agree, though, that his critiques are more effective than his positive vision, if one could derive such from his writings. Certainly his periodic attempts to reconcile himself to Freud’s vision of settling for second best” do ring hollow, at least to my ear.

Ok thanks for that. Read Triumph of the Therapeutic and Deathworks, but that was a hard read for me. So have doubts about my thinking there. Wasn’t being facetious. Appreciate the response.

You might check out the section “Toward the Fourth Culture” in “Crisis…” I expect that would leave you with some more food for thought.

Cheers

Comments are closed.