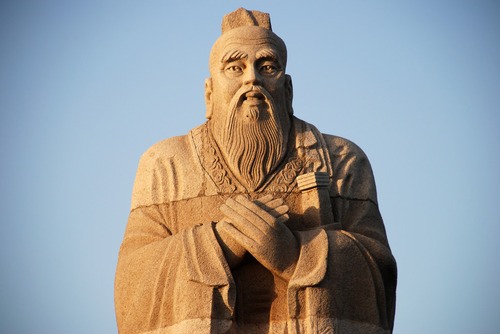

Confucius deserves a place of honor on the Front Porch because he was History’s keenest observer of the traditions and rituals that make life civilized. He lived in a time of social upheaval when changes in agriculture and communications led to large population increases that eventually shifted the balance of power to larger, younger states. With the barbarians at the gates of the older, more dignified principalities, Confucius was concerned about identifying and preserving the most meaningful aspects of ancient Chinese civilization. He perceived that the most essential characteristic of civilization was not something tangible or easily described like wealth or education–it was the traditions that had evolved to refine human nature. By expounding on the perfection of earlier and often mythologized society, Confucius examined what it means to be civilized.

Confucius believed there is an almost magical quality about civilized life and the way that it provides for human dignity, and he called this quality “li.” Herbert Fingarette in his classic book on Confucian theory explains that li involves sublime patterns of behavior for mourning, marrying, fighting, as well as for being a spouse, a mother, a son and so on. Li is most deeply effective when personal presence is fused with ceremonial skill. It requires shared attention and engagement in a learned convention. A Chinese tea ceremony is an ornate example, but li is never far from a civilized life. Li is present in the customs and conventions that provide a framework for our formal responses to other people such as when we purchase an item or greet another person with a handshake. These interactions only appear natural and spontaneous to those familiar with the custom. Meals, according to Fingarette, abound with the potential to experience li: “To serve and eat in the proper way, with the proper respect and appreciation, in the proper setting–this is to transform mere nourishment into the human ceremony of dining.”

Li requires an openness and a sharing which leads to more dynamic interrelations and to a heightened community. It is the vehicle a polite society uses to guide individuals past their own instinct and self-centered reasoning and toward more beneficent endeavors. The patterns of human relationships are only meaningful when they rise above instinct and ego. Through li, the Confucian sage Xunzi writes, “the conduct is brought to perfection, the eyes and ears become keen, the temper becomes harmonious and calm.” Like all the sages of the East, Confucius believed an initiatory period of discipline and learning is necessary to achieve some degree of mastery over human instinct; however, the struggle against one’s natural tendencies eases as the sensibilities and the constraints of a civilized life become one’s own inner imperatives. To be self-disciplined and ever turning to li, Fingarette concludes, “is to be no longer at the mercy of animal needs and demoralizing passion, it is to achieve that freedom in which the human spirit flowers.” Li is that aspect of tradition that engages us most fully as human beings and allows us to best affirm the dignity of others.

The customs and rituals necessary to evoke li evolve from earlier traditions and cannot be legislated or mandated. However, the vitality of tradition and ritual tends to calcify over time. Successful leaders, according to Confucius, renew old traditions and help guide the direction of culture to raise the civilized above the barbaric: “Govern the people by regulations, keep order among them by punishments, and they will evade shamelessly. Govern them by moral force, keep order among them by ritual, and there will be not only shame but correctness.” Li makes difficult tasks simple and brings order to chaos” “With correct comportment no commands are necessary, yet affairs proceed.”

A good and harmonious society is one that is endowed with traditions and rituals brimming with li. Li elevates human thought and behavior to a nobler and higher plane. This is possible because Li does not derive just from the natural order. Confucius constantly invoked the idea of Heaven where the pattern of perfection is set. Meaningful rituals have transcendent value because they are grounded in the spiritual. The Confucian philosopher, Mencius, concurs: “What the gentleman has as his true nature cannot be added to even by the greatest deeds of rulership and cannot be diminished even by dwelling in poverty.”

Confucius remains relevant because the resonating experiences of the past that were captured to construct tradition and culture through the sweep of generations still speak to us. Steeped within them is the pathway to our higher nature. The successful societies of the future, like those of the past, will be nourished by traditions which enliven human relationships. A truly engaged society guided by life-affirming li will not come into fruition through a blaze of insight. Rather, as Confucius taught, a more sublime way of life must evolve from traditions we already know.

Greetings from Canton.

Great stuff.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot with my children. Discipline is only effective in the short term if it doesn’t instill rituals or “liturgies” that help teach self-discipline. A lot of wisdom in thoughtful ritual.

Xunzi is another good Confucian book emphasizing the power of ritual/pattern to shape civilized life. I recommend it (in addition to works by Confucius himself, of course).

Thanks. Nice to hear from someone from my neck of the woods!

I know approximately nothing about Confucius. One of the very few things I have heard about is the concept of “the rectification of names” which seems to me to be strongly needed by our modern world, where jargon and obfuscation reign supreme.

As I studied many religions in the late 60s & 70s I did read Confucius’ writings. While many western people read the commonly-quoted lines which are definitely the choice bits. But if one was to plow through his writings one would find that most of Confucianism is confused, certainly disorganized, plus often self-contradictory or outright nonsensical. Confucianism is difficult to understand because it’s unclear and vague, thin and weak, not to mention tangled and illogical. Confucius himself said that his expertise were odes and ancient sacrificial rituals, not practical matters. While one can cherry pick his writings and sting together good thoughts or ideas but in the end the substance and spirit of his teachings have retarded Chinese development ever since. His teaching on leadership states men must be educated and of high moral value. Modern Chinese leadership, that enslaves and kills as well as “re-educates” its own people are not following his standard. Confucian thinking were prissy manners and empty rituals as these lead to good government: “He who understands the ceremonies and sacrifices to Heaven and Earth, and the meaning of the several sacrifices to ancestors, would find the government of a kingdom as easy as to look into his palm.” The Doctrine of the Mean. Confucianism reveals a very naïve grasp of sociological principles. The world has long since moved on from where formalized ritual could be a sound basis for governing a complex society.

Confucius was the leading light of a culture that rivaled the West for much of the last 2500 years, so he should not be dismissed as “prissy.” However, I agree that his Analects can be challenging and even amorphous. That is why Fingarette’s book is such a gem.

Comments are closed.