The soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still, and shall make men sensible by the expression of his countenance, that he goes the missionary of wisdom and virtue, and visits cities and men like a sovereign, and not like an interloper or a valet.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

On dating apps like Tinder or websites like OKCupid, the two most common aspirations listed on personal profiles are Netflix binge watching and traveling. Similarly, time spent backpacking in Europe is a recommended spiritual goal for the college graduate. Traveling to beautiful and famous places to acquire experiences is a “scientific” way we promise ourselves happiness. Wanderlust is an ideal. But it’s nothing new. Nor is it meaningful.

During the 17th-19th centuries, wanderlust masqueraded as a rite of passage called “the Grand Tour.” The idea was that exposure to famous, beautiful, and cultured places throughout Europe would through a kind of osmosis transfer meaning, culture, in a word, character to visitors. This idea still lingers. It’s the pull behind every advertisement in buses, trains, and subways urging you to end your sadness, find beauty, and become someone new–anywhere but with the people and places you call home.

The Grand Tour had its contemporary critics, my favorite one being Ralph Waldo Emerson, who himself was inspired by the Stoic philosophers criticizing wanderlust in the first 200 years after the death of Christ. People have been traveling for questionable reasons for a very long time.

Any reader of Emerson’s most famous essay, “Self-Reliance” (1841), will notice that he spends a large portion of the lecture’s conclusion attacking wanderlust–that is, the desire to travel for the sake of traveling–as if it were a desirable goal in itself. Though it was a controversial opinion in his own day, and still is, Emerson was critical of traveling as an ideal.

Both Emerson and the Stoics argued that wanderlust is an empty ideal that can make our lives less meaningful and disconnect us from those around us. Rather than seeking the world’s wonders through travel, they said, we should learn how to cultivate our capacity to wonder at home. We should live at home like travelers, discovering in our relationships and immediate surroundings the keys to a life well lived. Traveling may be beneficial, but only when our duties, families, and friends call us forth, or if traveling will improve our character in a way that staying at home could not. Good travelers create a home everywhere, and they seek virtue and wisdom wherever they are.

These ideas tends to rub people the wrong way. Emerson clearly saw that his polemic against traveling in “Self-Reliance” (1841) and “Art” (1841) was controversial and misunderstood by his critics, because in a lecture on “Culture” (1860) published nearly 20 years later Emerson felt the need to defend his skepticism about wanderlust. In his words:

I am not much of an advocate for traveling, and I observe that men run away to other countries because they are not good in their own, and run back to their own because they pass for nothing in the new places. For the most part, only the light characters travel. Who are you that you have no task to keep you at home? I have been quoted as saying captious things about travel; but I mean to do justice. I think there is a restlessness in our people which argues want of character.

Emerson is skeptical about wanderlust because he suspects that often but not always habitual wanderlust is inspired by a frustration with our own surroundings, duties, and tasks, a frustration which more often than not is our own fault, a vice of our character.

As Emerson put it when he first began to criticize wanderlust in “Self-Reliance”: “It is for want of self-culture that the superstition of Traveling, whose idols are Italy, England, Egypt, retains its fascination for all educated Americans.” Emerson suspects we often mistakenly imagine the source of our problems resides in the people and place we call home, rather than ourselves.

Yet, though Emerson criticizes wanderlust, he is not categorically opposed to traveling; there are bad and good reasons to travel. Travel can be done well. It can be done poorly. It is good to travel if you do it to improve your character, or if traveling supports relationships at home which cultivate your character. Conversely, it is bad to travel for any other reasons. If we travel because we are sad, disappointed, or frustrated, we will still carry our sad, disappointed, and frustrated self wherever we go.

As Emerson puts it in “Self-Reliance”:

I have no churlish objection to the circumnavigation of the globe, for the purposes of art, of study, and benevolence, so that the man is first domesticated, or does not go abroad with the hopes of finding somewhat greater than he knows. He who travels to be amused, or to get somewhat which he does not carry, travels away from himself, and grows old even in youth among old things. In Thebes, in Palmyra, his will and mind have become old and dilapidated as they. He carries ruins to ruins.

Traveling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome, I can be intoxicated with beauty, and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from.

Likewise, a quest to see famously beautiful sights is also no reason to travel. As Emerson quipped in his lecture “Art” (1841).

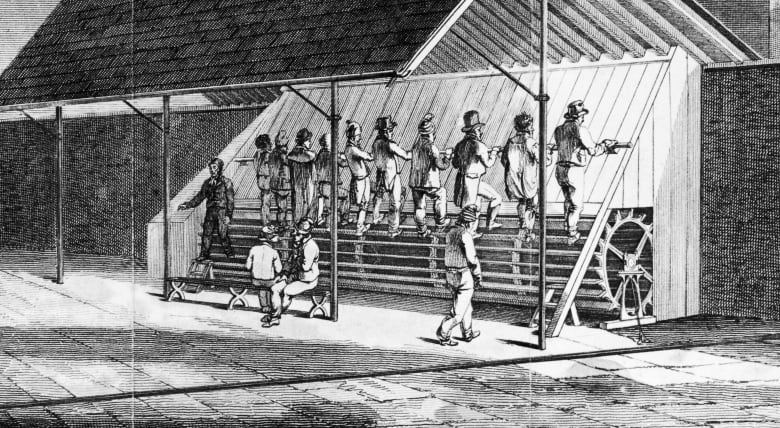

Though we travel the world over to find the beautiful, we must carry it with us, or we find it not. […] That which I fancied I had left in Boston was here in the Vatican, and again at Milan and at Paris, and made all travelling ridiculous as a treadmill.

Wherever we go we carry our character with us. So, rather than seek beautiful places, we should learn to find beauty within our character and sculpt our character into something more beautiful. If we learn to “improve” who we are through “self culture,” as Emerson puts it in “Self-Reliance,” we could become as “brave” and “grand” as the famous sculptures of the ancient Greek sculptor Phidias. We would not need to seek beauty abroad, because we could reveal the beauty wherever we are.

Emerson’s polemics against wanderlust may seem senselessly provocative at first blush. But the reasoning behind them, as well as their provocative style, derive directly from the written works of Stoic philosophers. See, for example, Seneca, a Stoic philosopher who dedicated one of his letters to criticizing his friend’s wanderlust in terms that clearly served as a model to Emerson:

Do you think that you are the only one this has happened to? Are you amazed to find that even with such extensive travel, to so many varied locales, you have not managed to shake off gloom and heaviness from your mind? As if that were a new experience! You must change the mind, not the venue. Though you cross the sea, though ‘lands and cities drop away,’ as our poet Virgil says, still your faults follow you wherever you go.

Here is what Socrates said to a person who had the same complaint as you: ‘Why are you surprised that traveling does you no good, when you travel in your own company? The thing that weighs on your mind is the same as drove you from home.’ What good will new countries do you? What use is touring cities and sites? All your dashing about is useless in the end. Do you ask why your flight is of no avail? You take yourself along. (Letters on Ethics. L28. Trans. Margaret Graver and A. A. Long.)

Seneca suggests that the cure to sadness is a change of character, not a change of air. This matches Emerson’s warnings that we should not travel to cure sadness, and the reason is simple. Emerson read Seneca cover-to-cover, as well as the two other major Stoic philosophers, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. In his lecture, “Books,” Emerson went so far as to claim these three Stoic philosophers wrote “the Best classes of Books” as well as the “Bibles of the World.” Furthermore, as Robert D. Richardson has argued, Emerson was frank about his admiration for Stoicism, openly considered himself a Stoic, and saw transcendentalism in general–and his famous ideal of Self-Reliance in particular–as Stoicism “cast into the mould of these new times.” Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius are the Stoic roots of Emerson’s criticism of wanderlust.

Like Emerson, Epictetus observes how his contemporaries are willing to go on expensive, difficult, and tedious journeys to see beauty, but have no equally powerful desire to perceive the beauty around them (Discourses. Bk 1.6.23). Rather than seek beauty elsewhere, Epictetus urges that we should learn to sculpt our character into something virtuous (Bk 1.15.2). Epictetus offers as an example Phidias’s famous statue of Zeus as a model for our self cultivation (Bk 2.19.22). Emerson’s rhetorical debts to Epictetus are unmistakable.

It should therefore not surprise to see that Emerson owes similar debts to Marcus Aurelius, who like Emerson in “Self-Reliance,”argued that only with a virtuous character can we avoid sadness, find beauty, or achieve inner peace:

People try to get away from it all–to the country, to the beach, to the mountains. You always wish you could too. Which is idiotic, you can get away from it anytime you like. By going within. Nowhere you can go is more peaceful–more free of interruption–than your own soul. Especially if you have other things to rely on. An instant’s recollection and there it is: complete tranquility. And by tranquility I mean a kind of harmony. So keep getting away from it all–like that. Renew yourself. (Meditations. Bk 4.3 Trans. Gregory Hays.)

There is no question Stoic philosophy animates Emerson’s criticism of wanderlust throughout “Self-Reliance,” “Art,” and “Culture.” But again, neither Emerson nor the Stoics are categorically opposed to traveling, just to wanderlust.

Wanderlust is a vice, not a virtue. It encourages us to locate the sources of all our problems in the people and places we call home. This prevents us from being at home anywhere, because it locates home wherever we aren’t.

We desire to wander, Emerson suggests, in order to learn from others how to be at home. In “Self-Reliance,” he notes that “They who made England, Italy, or Greece venerable in the imagination did so by sticking fast where they were, like an axis of the earth.” Why else do half a million people visit Walden Pond each year? By “sticking fast” to their Walden Ponds “like an axis of the earth” people like Thoreau make places meaningful.

Emerson and the Stoics remind us we can do the same. They challenge us to live at home like travelers. We can find beauty, wonder, and happiness in the people and places of our everyday lives–if we try.

So a bunch of overprivileged dudes want to keep everyone locked at home so they never learn that other people have better lives. Got it.

Seriously, wanderlust is prompted by the desire to get away from bad situations. If you want people to stay stuck, make being stuck attractive. That, in a few words, is my whole objection to your ‘localist’ project. I grew up in a small town and hated every minute of it. Make small towns less hateful and people will stay.

Karen, I think you are misunderstanding my article. Emerson and the Stoics would encourage you to leave the kinds of bad situations you refer to. Their issue is with wanderlust, not avoiding the company of the vicious. They would encourage you to leave the company of the vicious, and they would not consider this wanderlust.

The problem with their analysis is that often one doesn’t know that one has vicious company until leaving it gives perspective.

Karen,

I have to disagree. While it is not the subject of this post, I am aware that both Emerson and the Stoics offer criteria for determining what kind of company you should keep or not keep. Furthermore, more generally, I don’t see why you must travel somewhere else to realize that people that make up your home might be morally dubious. You don’t need to be a traveler to properly judge someone’s moral character, you just need to be wise.

I leave it to you to decide if this is critical or not: I’ve long thought that travel’s virtue consists in its ability to make one appreciate the virtues of home. In my younger days, I used to spend several weeks at the end of every summer living out of my car, trout fishing. No pressing family commitments, nobody saying I had to be anywhere at any time.

It was great. But, looking back on it, that level of freedom was starting to wear thin, by the time I got married.

Likewise, I once spent a summer studying Russian in Vladimir. Not only did I see all kinds of sights in Vladimir, but that summer happened to be the 300th anniversary of St. Petersburg, and so there was even more going on there, than usual. Got to Moscow, saw the usual sights there, too. But overall, I didn’t enjoy any of those places very much, and frankly found any place with that much asphalt and concrete to be depressing. What I did enjoy a great deal, however, was the time I spent out at a small dacha outside of Vladimir. It had a big weedy garden, I went out in the woods picking mushrooms, and I spent a bunch of time hanging out in the homemade bania (Russian sauna). Likswise, I visited some really neat (lame descriptor, I know) Russian churches, in rural areas where it seemed like actual people might actually go there. One of the churches was in the process of getting a new roof, and it still irritates me to this day that I didn’t get a chance to learn anything about how you mold metal roofing around those onion domes. (I’ve been a sometime roofer, before college and in summers now that I’m a university professor, though my knees have lately caused me to focus more on building furniture as a sideline).

All these things have, in hindsight, made me much more appreciative of my own home. I think it was important that I did that in the wanderjahr period of life., though, when my desire to travel was out of genuine interest and not out of fundamental dissatisfaction with where I came from. When I was in late grade school, I took a trip to Japan for several weeks, with my grandfather, whose worldview generally exemplifies all the downsides of travel depicted here. I’ll never forget that when we came back, everything in Japan was then “better” than here, exhibit A in my grandfather’s view being the convex mirrors on street corners in Japan.

So, I do think that some travel when one is younger can be good, but I think if one is fundamentally rootless to begin with, probably not much good will come of it. If one is rootless, travel largely serves as fodder for confirmation bias, at least in my experience.

Thanks for your reply and thoughts Aaron!

You seem plenty “critical” of your own experiences to me. If I understand you properly, you find that some of your traveling was wise, and helped you cultivate a better character and relationship with your home and some of your traveling did not. You suggest that the key difference is whether or not one is “rootless” or not to begin with, which is an interesting way to consider the issue. What do you mean by that? It strikes me that the key difference between good and bad traveling in your examples is the motive and aims of the traveler rather than how rooted at home -or not you were. Based on your stories, your grandfather seemed to desire to travel to justify certain of his complaints about home, where you generally seemed to desire to travel to learn how to better live at home. The issue with your grandfather doesn’t seem to be his rootlessness in your example, but rather his assumptions and motives for traveling. Anyway, thanks again for your comment!

Thanks for the article. I often find myself surprised by Emerson, mostly because the reputation surrounding his overarching philosophy contrasts the practical positions he takes, like here for example.

Still, I wonder if his underlying basis—a total focus on the self and a privilege of the transcendental ego, even to the point where ‘finding’ and ‘founding’ converge—proves undoing to the argument here in the hands of someone less noble and realistic than Emerson. In short: the focus on the self can apply as easily to an authenticity-seeking wanderer as an authenticity-seeking devotee to home.

Thanks Casey!

“I often find myself surprised by Emerson, mostly because the reputation surrounding his overarching philosophy contrasts the practical positions he takes, like here for example.”

I couldn’t agree more. You’ve pretty much described my entire experience reading Emerson right there.

“Still, I wonder if his underlying basis—a total focus on the self and a privilege of the transcendental ego, even to the point where ‘finding’ and ‘founding’ converge—proves undoing to the argument here in the hands of someone less noble and realistic than Emerson. In short: the focus on the self can apply as easily to an authenticity-seeking wanderer as an authenticity-seeking devotee to home.”

I’m going to push back a bit on this.

I agree with you to an extent. I think Emerson believes we can only live a life well lived if we are “authentic,” but merely following our authentic desires will not lead to a life well lived. For example, a pedophile surely has authentic desires, though we, and Emerson, would question that them following their authentic desires is a good idea for living well! So it goes with wanderlust. Someone may have authentic desires, but that doesn’t mean those desires are good. Just because someone authentically suffers from wanderlust, it doesn’t mean they should travel according to Emerson. And Just because someone authentically wants to stay at home, it doesn’t mean they should according to Emerson. This is why I don’t think “the focus on the self can apply as easily to an authenticity-seeking wanderer as an authenticity-seeking devotee to home.” Regardless, thank you again for your kind words and thoughts!

“You suggest that the key difference is whether or not one is “rootless” or not to begin with, which is an interesting way to consider the issue. What do you mean by that?”

My grandfather is incredibly well-travelled. And yet at the same time, he’s one of the most parochial people I know. He’s been all over Asia and the Middle East, Europe and South America. When he was in his early 80’s, he rode his bicycle clear around Sweden. Yet, this is the same guy who unabashedly reads only books whose perspective already agrees with his.

I’ve long tried to make sense of this paradox, and the answer I’ve arrived at is this: My grandfather has lived in the same town, in the same house, since the early 60’s. I don’t think he’s ever viewed that place anything more than a problem to be solved. His travels, therefore, have largely functioned as confirmation bias as to his his irritation about what’s wrong with home,. Thus, my argument that “rootless” is the right description for somebody who can live in the same place for that long, and be convinced to the core that the only thing keeping his place down is Washington Republicans, cue melodrama villain laughs….. When he and his friends get together, what do they talk about? How great the German welfare system is, how clean Japanese parks are, how you can’t get a Swedish egg cup locally, and how nobody in Washington will demand that the rest of the locals of their area kowtow to my grandfather and his friends’ desired local and state-level changes. In sum, I’m arguing that my grandfather’s fundamental rootlessness is the cause of his current “residence” in a kind of never-never-land imaginary world of international travel where the only standard of value is whether something is “Interesting” or not. This putatively “cosmopolitan” world is actually incredibly parochial, in practice, all the worse because it isn’t an actually existing place, a “utopia” in the literal sense.

Whereas: I think my own travelling experiences, though far narrow than my grandfather’s, have oddly made me less parochial than he is, because I had roots in a couple of places when I started out. So, the Hermitage and Russian cabbage soup are not a priori evidence that America is full of idiots who think Larry the Cable Guy is capital C “Culture,” (though I’ll take that over Duchamp or the “Piss Christ” any day), but neither is my deep conviction that Russians can’t make a decent pizza to save their lives evidence of the reverse. In short, I appreciated my time at the Russian dacha more, because of my roots in place.

This, I suggest is valuable, and I so think that travel does have a role to play in a life well-lived. Looking over your comment, it looks as though we’re actually arriving at quite similar answers, but from different starting points.

Good article, Aaron

Hi again Aaron,

Thanks for clarifying what you meant and sharing your interesting and relevant story about your Grandpa!

Christopher, this is a fantastic piece. I hadn’t really considered this aspect of Emerson, nor his connection with Stoicism being this strong.

As they say, few problems have a geographic solution because everywhere you go, there you are.

You have a fantastic writing style and sharp philosophical orientation. Would you be interested in republishing this piece or writing in another outlet? If so, please consider https://erraticus.co/submissions/

You can also email our editorial team at submissions@erraticus.co should you have other questions. Good luck with the rest of your writing. The world could use more perspectives like yours!

Thanks for your kind words Jeffrey Howard. Glad you enjoyed the article!

Well written and awesome quotes! Emerson and Confucius are two of my heroes, but so different.

Thanks Willis!

I feel the same way about both figures. I think they have far more in common than is usually suspected though!

I think it really depends on the extent and the type of motivation behind the will to travel. I totally agree that travelling due to sadness of being stuck in a place will bring sadness with you to the end of the world. I would also like to say that the world is amazing and exhilarating and it can teach us a lot about a lot of things anx their coming into existence. When you meet a stranger and is accepted or rejected, welcomed or ignored you kind of adapt and the place or the person you are interacting with does not remain strange to you. You learn to be yourself in the midst of all the varied beauty in different people and different places. I also believe that being connected to a single place and the people around you and in your lives can give you a sense of awareness about your roots and who you are. I believe the people you love and who love you have the power to make you feel whole and being in such a connected state can jeep you happy but occasional travelling for inspiration and learning and observing art and culture is definitely worth it.

Hi Shailesh,

Agreed, travel can serve a purpose in a life well lived. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

Not a ding on travel proper but shallowness — slow clap/Captain Obvious/fish in barrel endeavor if ever there was one.

If ‘We should live at home like travelers’ it’s good; if Emerson larked enow to carp about it …

Don’t travel like a ninny but anyone who has wandered around Chartres or Calcutta or on I-70 in Colorado and wonders why (without wondering) hasn’t eyes for seeing.

Hi Paul Hughes,

I don’t fully follow you, could you clarify what you mean here?:

“If ‘We should live at home like travelers’ it’s good; if Emerson larked enow to carp about it …Don’t travel like a ninny but anyone who has wandered around Chartres or Calcutta or on I-70 in Colorado and wonders why (without wondering) hasn’t eyes for seeing.”

Finally, perhaps I am misunderstanding you, but I don’t exactly see your point here either:

“Not a ding on travel proper but shallowness — slow clap/Captain Obvious/fish in barrel endeavor if ever there was one.”

I think you are suggesting this article is questionable because the point it makes is obvious to you. But, it strikes me that it really doesn’t matter what I or you find as obvious/common sense for two reasons. 1. Common sense is rarely common practice. 2. Common sense needs to be re-articulated from time to time regardless, otherwise it decays into banal cliches which cannot motivate proper action. Did I understand your criticism properly, or was it something else?

This neglects the extreme difference between traveling in youth –to say, age 25 or so– and any time thereafter. Through one’s mid-20s there is a “broad horizons” curiosity, an almost physical yearning to adventurously “cast out”, “see the world”– to gain context and perspective by passing geographic and other boundaries, whether or not we appreciate alien cultures, mores, usages in bumbling through.

“Wander” is not the word for this… my own objectives focused on experiencing worlds-on-worlds, knowing I’d likely never pass that way in such a vulnerable mode again. Among other things, traveling young, without encumbrances, means you don’t pose a threat in venues that in retrospect loom deadly dangerous. You may not know this at the time, but with maturity comes circumspection in the sense of “Good lord, why am I still here?”

Of course, this doesn’t simply happen– one has to seek it out. However naive, impecunious, those who feel this urge will find a way. By age 25 I’d been a merchant seaman to Bombay, a bush pilot in lion-country Tanganyika; a USAF crypto-intelligence officer in the Aleutian Islands, a global hitchhiker who’d bucked tanker-rigs across the Khyber Pass from Peshawar to Kabul and points west. Whatever followed –didn’t settle down to the mid-40s– nothing beats those earlier adventures; Emerson be damned, defining memories suffuse one’s whole persona.

Advice to Emerson’s constituents: Please understand that “Being exists in essence as Potential, for not in Being but Becoming lies The Way.”

Comments are closed.