The official scorekeeper for my sixth-grade baseball team was our catcher’s mom. Sometimes she couldn’t be there, and it would fall to our coach to keep score. Sometimes he didn’t feel like doing it, in which case it would be up to me and my teammates.

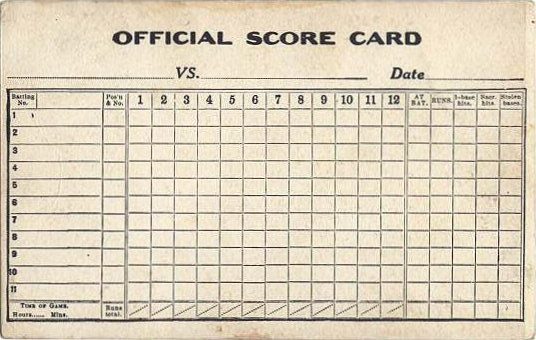

I have only vague memories of holding the scorebook in my lap, asking my teammates for help as I recorded outs and hits and tracked the progress of runners on the base paths. Did I—we— do a good job? Were we accurate in our assessments? Unlikely. If we kept score as well as we played, those scorecards were artifacts of incompetence.

But who cares? As far as I know, the only reason we kept a scorecard was so that someone could call the local newspaper and report the game’s outcome and notable statistics: who pitched, who got hits, who scored runs. A few times a week, the sports page printed a roundup of local Little League games.

If we take seriously the central claim in Alva Noë’s new book, my teammates and I weren’t just taking down notes. We were engaged in an act quintessential to the nature of baseball. We were, in a small way, philosophers of the game. Which is to say, we were people thinking about the game and arguing about the game and, in important ways, making the game. We were doing what baseball invites us to do.

Noë is a professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. The book—Infinite Baseball: Notes from a Philosopher at the Ballpark—is largely a compilation of entries he wrote for NPR’s now-defunct science blog 13.7: Cosmos and Culture. The book is divided into five sections, each of which juxtaposes baseball with broader questions about, for example, language, or human agency, or attention.

Baseball, it seems, has never been far from Noë’s mind, even when he’s dwelling on more ethereal topics. In previous books, he has repeatedly drawn on the game of baseball for examples and metaphors. In Infinite Baseball, it becomes clear both that Noë loves the game, and that baseball really can provide a handy framework for philosophical inquiry.

Noë’s central point in this book is that baseball is a “philosophical game.” Calling the game philosophical doesn’t mean it’s particularly intellectual, or that every baseball player is a philosopher. It means rather that baseball is a game concerned with itself:

With some activities we can distinguish the activity from thought about the activity. We can distinguish, as it were, theory and practice. But some activities contain, as modes of themselves, theory. Some activities, the ones I call practices, always require reflection. Baseball is one of these. To play baseball is to engage with the problem of baseball. Baseball is a problem to itself.

For Noë, the self-reflective nature of the game is brought out most clearly in the act of scorekeeping, whereby a scorekeeper must make judgements about, for example, what counts as a hit (versus an error) or a wild pitch (versus a passed ball). These are questions that can only be answered within the context of the game of baseball. In order to make those decisions, we must think carefully about what a hit is, or what an error is. Such decisions require judgement.

Consider the strike zone. Noë makes a fascinating argument about role of umpires, particularly when it comes to judging balls and strikes. The strike zone, he says, is not so much a three-dimensional space as it is a “zone of responsibility.” A “strike” is a pitch that the hitter should be able to hit, so we can therefore fault him for not hitting it. A “ball” is a pitch that he should not reasonably be expected to hit, so we therefore don’t fault him for not hitting it. That an umpire must render judgement for every pitch—and that players, managers, and fans often argue about those decisions—is appropriate for a sport that invites self-scrutiny.

Scorekeeping—the thing that I and my teammates did all those years ago—is fundamentally an act of assigning blame (a “forensic activity”) for what happens on the field. The scorecard itself captures an interpretation of what has happened. “Baseball is about what people do, about what they accomplish in the social setting of the game,” Noë writes. Determining what players have done—committed an error, failed to swing at a strike—is something that requires human judgement about questions of intent and effort, no different than how a judge or jury must decide whether a victim’s death was murder or manslaughter or something accidental.

Noë is quick to point out that baseball is not alone in raising questions about itself and interpreting human intent. Other sports offer a similar opportunity for self-reflection, as do many or even most complex activities—activities that Noë has elsewhere described as “organized activities.”

“It is the hallmark of all characteristically human activities—language, the law, other sports—that they are, in the sense I am trying to understand, baseball-like,” Noë writes.

If baseball is unique, it’s because the game makes explicit this loop of practice and interpretation through the act of scorekeeping. It formalizes the process of thinking about and commenting upon the game, which in turn affects the way the game is played. Keeping score is important work. It is a “knowledge-making activity,” and one that every baseball fan, in theory, participates in.

Making judgements, interpreting actions—these are skills that require attention, knowledge, and a familiarity with the larger practice in which they take place. In other words, they require work. And they are not—I repeat, not—something that can be automated, nor should we want them to be. Looking outward to other “baseball-like” activities, Noë observes, “It would be a dark consequence of life in the digital age if we forgot that keeping score is more than keeping track, and that each of us has the power to keep score.”

This is good stuff. I recommend the book to anyone who loves the game. For as short as the book is, it’s impossible to capture the breadth of Noë’s meditations. The section on steroid use is thought provoking, drawing on arguments about consciousness and human action that he put forth a decade ago in Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness. And the final section finds him reflecting carefully on what it means to be a fan of the game. (That he is a fan, specifically, of the New York Mets may partially explain why he has spent so much time thinking about baseball; it sure beats watching the Mets).

The book is also a fitting follow-up to Noë’s previous book, Strange Tools: Art and Human Nature. There, Noë reflects at length on how art and philosophy are tools that allow humans to understand the practices that organize us. In Infinite Baseball, he shows us how baseball is one arena—one organizing practice—in which this constant loop of activity and reflection is at work. Noë suggests that one reason so many books get written about baseball is because baseball, through its formal concern with forensic matters, essentially invites the kind of reflecting and writing in which he himself is engaged.

But all of this thinking about how baseball provokes thinking eventually may cause us to think up another question: why do we care about baseball in the first place? What draws philosophers like Noë to spend countless hours of his life watching grown men play a game? Noë rejects the notion that there is anything inherently superior or noble or particularly “American” about the game. His answer, so far as he has one, reverses the equation: “[Baseball] is special—it is special—because we care so much about it.”

He might be right, though I’m not sure Noë brings us closer to a deeper understanding of baseball’s place in our lives. To some extent, we may have to accept that baseball just is embedded in our culture. If there is any truth to the myriad clichés about baseball and America, or baseball and childhood, or baseball and lazy summer evenings, it’s only because some people have suggested there is. Such notions, once spoken aloud, affected the way we collectively talked about baseball, which then affected the way we played baseball and watched baseball, which in turn affected the way we talked about baseball, which then affected the way…you get the picture.

And so the feedback loop of activity and reflection kicks up a notch. “Baseball is, in a sense, a myth, but we make it real by acting it out,” Noë says. He ponders in what ways it’s all right for people like him, for people like me, to care so much about the New York Mets, or the Milwaukee Brewers. The game is not just a game; it’s a business. Vast sums of money are in play. Are we rubes for getting sucked in?

The biggest lesson, for me, of Noë’s book is that it’s impossible to talk about “the game of baseball” in any abstract sense. When we love baseball, we love something that is messy and ever-evolving. The sport does not exist separately from the way the sport is practiced. If you sometimes find yourself longing, whether vaguely or explicitly, for a “return” to the bygone amateurism of baseball’s earliest days, well—it’s time to wake up. Noë makes the argument in Strange Tools that it is literally impossible for modern humans to conceive of spoken language as it may have existed prior to the invention of writing. Our own concept and use of language is too proscribed by the written word.

In the same way, it’s literally impossible, in 2019, to conceive of baseball without Major League Baseball. It’s impossible to conceive of baseball without multi-million dollar, publically-funded stadiums. Without PEDs and salary arbitration and commercials between innings. Youth baseball has been coopted by companies that wring profit out of 14-year olds who throw hard. It is the lot of every father who has ever watched or will watch his son pick up a baseball bat to dream, however momentarily, of a future in the big leagues. This wouldn’t happen without Major League Baseball and its downward pressure on every level of the sport. Yet Major League Baseball wouldn’t exist if we didn’t love the game.

What is the appropriate response to this dizzying cycle? Is it irresponsible to pay to watch professional baseball players who, you can make a reasonable case, are underpaid? Is it wrong to perform Tommy John surgery on a 15 year-old? If we, through our actions as fans, necessarily contribute to the burdens and rewards of a professional baseball career, can we be surprised when players skirt the rules?

I don’t have definitive answers. I’m guessing you don’t either. Certainly it’s important, though, to wrestle with these questions. We might dig and dig without ever striking the bedrock upon which our affection for baseball is built, but there is value in inquiry—especially in a game like baseball, which makes philosophers of us all. “Although we don’t choose our loves for reasons, we are condemned at last to admit that, our loves are not beyond reason or indifferent to critical evaluation,” Noë suggests.

Despite the thorny questions it raises, plenty of us do love baseball. Rightly or wrongly, nobly or foolishly, and we always will. So we play on. And, as best we can, we keep score.

So it’s like George Will on steroids?

Comments are closed.