Here’s a tale of a place, told in a line of families, told in their daily work for their daily bread. The first arrive, on the edges of living memory, as settlers to a sandy slope of land in northern Michigan—Dutch immigrants, loggers and farmers and builders of industry. Two of those settler children grew, met, married, and gave birth, to my grandmother. That was 1915.

Ninety years on, in the summer of 2005, my wife and I were married. The hitching together of our love and our daily work and our joys and worries added a new family to that line. As part of this joining, I moved the space of a few counties to live in the house she had bought some years before. My lover and I dreamed and schemed of a life together on the land. I would raise a few fat hogs and some grain for our daily bread. She would devote her life to tomatoes. Together, we would tap the maples and raise bees for honey.

We spent that early summer planning our wedding while driving back and forth to Grand Rapids, to visit my Grandma in hospice. During one of those visits, we were surprised to learn that she was born less than a day’s walk from the house where we now lived. The tale of our line returned to the tale of that place.

That place—the town she was born into, Atwood, Michigan, still exists, if only as reproof to all the reasons it shouldn’t. Atwood is another small town just along the way, and so is fading away. Just over a century ago, though, on the back of the displaced natives, it was part of a promise to the emigrating Dutch families—here was a place to farm, and to log the hardwoods and pines, and to build industry, and to make a community and a life. And for a while, they did.

If you squint, you can start to see the daily life of these folks—the mix of old European traditions, and the skills required to adapt to this new land of sand and white pine. Maybe, if the wind winds around from just the right direction, and the day is clear and quiet, you can almost hear the steady rhythm of those tasks of subsistence and thrift—the call of the daily work, and a slow, patient accumulation of folkways and a place-based culture.

This speaks to a time when communities, by necessity, maintained a broad set of practices around self-sufficiency. Before railway stubs and asphalt roads, the transmission of culture came at walking pace. Before news and music came over the “wireless” via rural electrification and the AM radio, the people in these places accreted a “folklife.”

A folklife is made up of the food and craft, the local stories, songs, remedies and rumors—relationships that define a place as much as the geology and ecology do. Look at any long-sustaining, resilient culture, like that of the Great Lakes’ displaced Chippewa and Odawa, and you’ll see that their folklife all points back to a wisdom of caring for the place, with story after story of self-control, reciprocation, not taking too much, leaving plenty for others, and completing the generative exchange. More than ever, we now need to remember these lives, these people who lived them, those who came before, and the lessons each learned about how to become a part of this place.

Sadly, though, we believe that we are not they. We, instead, are the architects of the fossil-fueled technological age, and so we’re happily beholden to our tools—from the automobile to the smart phone—that arrive embedded with their own proffered narrative: eternal progress.

We grapple with the promise and peril of these tools and our use of them, and so we forget to remember the past. We are entranced, like all settler pioneers, with a notion of destiny—with the promise of the techno-utopian future, or its twin, the end of all things. Our visions of the future bifurcate, based on how well we think our tools will continue to serve us. On the one hand, we can trace the lines from our smartphones and screens toward a gleaming dream of the chromium steel interstellar ship—driverless, of course.

On the other hand, behold: the 24-hour news cycle, awash with images, if you care to see, of calving glaciers and drought-fueled starvation. Refugee camps and caravans. Drones and dirty bombs. The end of pollinators and with them, much of the world’s food supply. Off in the distance of the future hypothetical (version: dark): warlords, plagues, hunger. The rider on the pale horse. When the wind winds a certain way, and the light shifts, we can almost feel the cold shadow of the circling carrion on our neck.

We’re haunted by the enormity of the predicaments we and our tools have created—climate change, of course, but also resource depletion, from fading oil to the loss of arable soil, and massive pollution, and the sixth great extinction event. And in this, our haunting, we’ve come to believe only enormous solutions will suffice. We love thinking big, and we love thinking fast. The emblematic modern solution to our major environmental issues would be global in scale, cost a lot, and would happen overnight.

The emblematic natural solution, however, would be local, or even finer in scope, and would happen over generations. The evidence for this approach is thick in the bee-rich orchards and maple forests of northern Michigan, in a spadeful of soil. Diligent mycelia, the fungal fibers finer than root hairs, thread from tree to tree, scaffolding the soil in intricate architecture and facilitating the great economy of the subterranean food web: swapping soil nutrients for sugars. Mycelia travel miles to cover mere meters.

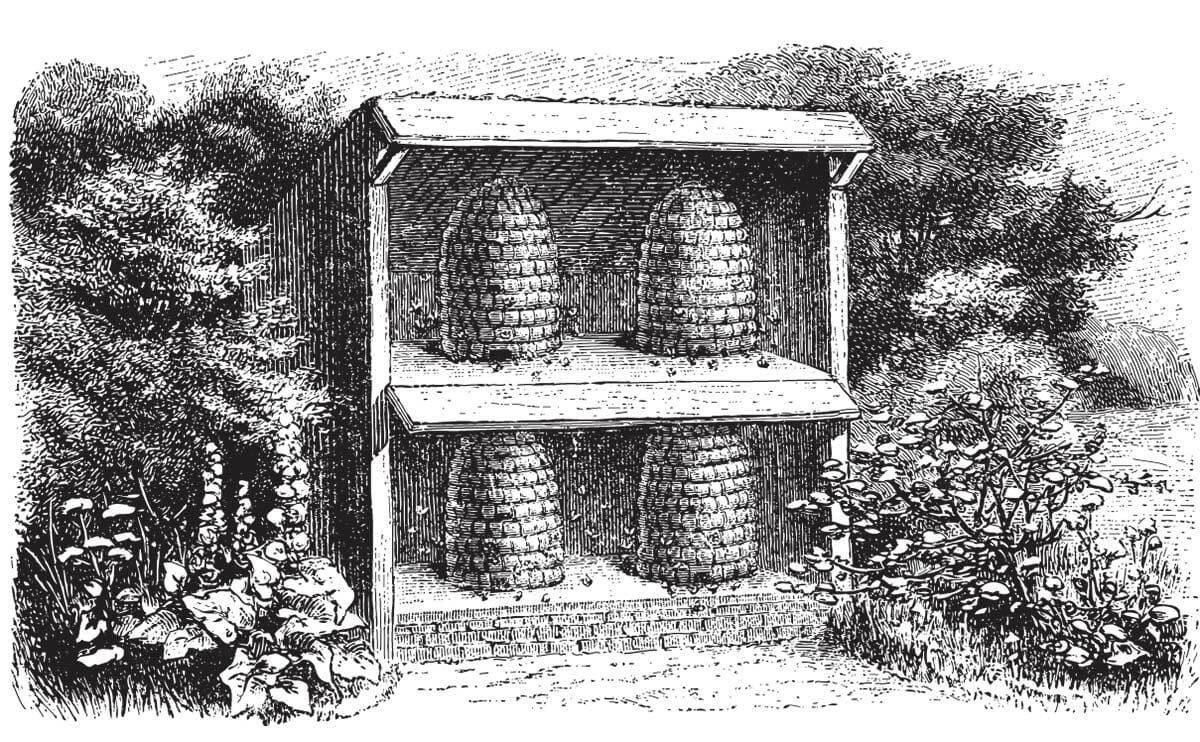

Further evidence is in the hives the settlers built, not for an original inhabitant of this landscape but for a welcome guest, the honeybee. Spending its life aloft, the worker bee facilitates the other half of the forest food web, an exchange between insect and flower—currency: pollen. In these tiniest of tasks, the honeybee feeds the hive and heals the world. There is no division between those two needs. There is only the humming steady rhythm of the daily work, meted out in the micro-est of transactions, for as long as the species survives. Even in a lean, dry year, a bee commute caps out at five miles. Its work is eminently local.

A metaphor ripe for the plucking can be found here, and I’ve come to call it the beehive plan. The idea is that we humans can find work of this character, that is at first good but that becomes great; that we can labor both to feed ourselves and our families, and in the doing of it can heal our small places. And what is the globe but a vast mosaic of small places?

There are two key instructions to tease out. First, I seek the restoration of relationship, with both my neighbor and my place, which doesn’t depend on my cleverness, the sophistication of my technology, the money at hand, or the permission of politicians. I restore my relationship with strong doses of affection and humility, and by keeping my work, like the honeybee, eminently local.

Second, that we, each of us, are capable of countless small acts of care, and in such is the restoration of the wild, the world, and the culture. In such is the conversion of the displacing colonist to the helpful, welcome guest.

A single worker bee might live six or eight weeks in the time of high forage; that bee will diligently spend the entirety of its life and work making about 1/12th of a teaspoon of honey, which it will never live to eat. The fruit of its work outlives it and is passed along for the next generation to feed on. May I be so blessed, to keep plugging away at my work in the world for another 40 years, until I’ll have made my 12th of a teaspoon.

My friend Dan Gorno was a dancer and a dance caller, a potter and a musician, and his community eats of his honey and remembers him and his work daily. I’m also nourished thanks to Bob Russell, a local scientist and activist who knew all along what we were facing and who patiently helped us build systems of governance and resilience to begin handling it. Both of them have passed on, and have passed on their work and their sustenance. Most importantly, I’m eating from a lifetime of sympathetic instruction and care from Thelma Sneller, my grandma, though she died that summer, just a few weeks before our wedding, at the age of 90. She lived a life that was quiet and rich in relationship, and in her patient working of the world she made some mighty fine honey.

This patience, this generational exchange, this view that the work will outlive us, is rooted in Vine Deloria’s explanation of the indigenous idea of the seventh generation. As I originally understood the concept, and as I usually hear about it in popular culture, we are meant to think seven generations ahead—to consider the impact any decision would have on distant progeny, and so curb our recklessness and over-consumption. Deloria, though, a Dakota scholar and theologian, articulates a different interpretation:

A good family could anticipate that a child born into it would know and remember his great-grandparents. If that person lived a good life, she would live to see her great-grandchildren. Each person, we might say, is the fourth generation and looks back to three generations and forward to three.

I never met and so I don’t remember my great-grandparents, but I can, with some straining, make out the outlines of their lives as my grandmother was born, in 1915, in Atwood, less than a day’s walk from where I now make the beginnings of a life of the land. My eldest daughter was born in 2010. If she lives to be 90, the age my grandma was when she died, she will wake to see the sunrise on New Years Day, 2100. In that time, she will possibly have grandchildren or great-grandchildren of her own. Or, like so many of us, will discover and cultivate a host of other relationships strong enough to call “family.”

The daily work of their lives I cannot anticipate except through great leaps of imagination. But there they are, fading into view through the passing years just as my great-grandparents recede, and just as the arc of my own life ticks slowly forward.

In thinking of each and all of them, I can say with surety very little: only that they ate, and will eat, that they loved, and will love, that they worried for their parents and for their children, and will worry. And for those yet to come: I know that my work, my daily acts of care, will feed them, though I do not live to see them eat. This, though, is why I go to work with attention, and go slow.

Thanks, Brad! Talking about “loving our enemies” tomorrow in worship. One of the ideas from a book I’m referencing is that the healing of the contempt culture is in relationships, local one-on-one interactions of love and respect. Like the bee, just 5 miles out… I’ll use that tomorrow.

One of the things I love about this site is that focus on one-on-one interactions—local encounters, woven reciprocity, trust, gossip and shared work—and how that love and respect can build something valuable in the face of national abstractions. Sorry I missed the worship!

Thanks for this beautiful article, Brad. My grandparents were farmers in Atwood, and that is where my father grew up. The family farm had a small orchard, and as a young man my father took up beekeeping. A few years ago I lifted seven field stones out of the earth on the old farm and transplanted them into my urban garden, where I regularly point them out to my children and grandchildren ( I guess that makes five generations). I’ve never lived in Atwood myself, but it feels like a place to call home: the views out over Grand Traverse Bay, rolling hills, country roads through solid Michigan forests, and the cemetery up on the hill where there is a cluster of headstones bearing my family’s name. It’s good to meet the neighbors.

Comments are closed.