This essay was first published in the Rutland Sunday Herald/Times Argus on October 13, 2019. It is written by Frank Bryan and John McClaughry, who co-wrote Vermont Papers. Bryan is a retired professor. McClaughry works at the Ethan Allen Institute.

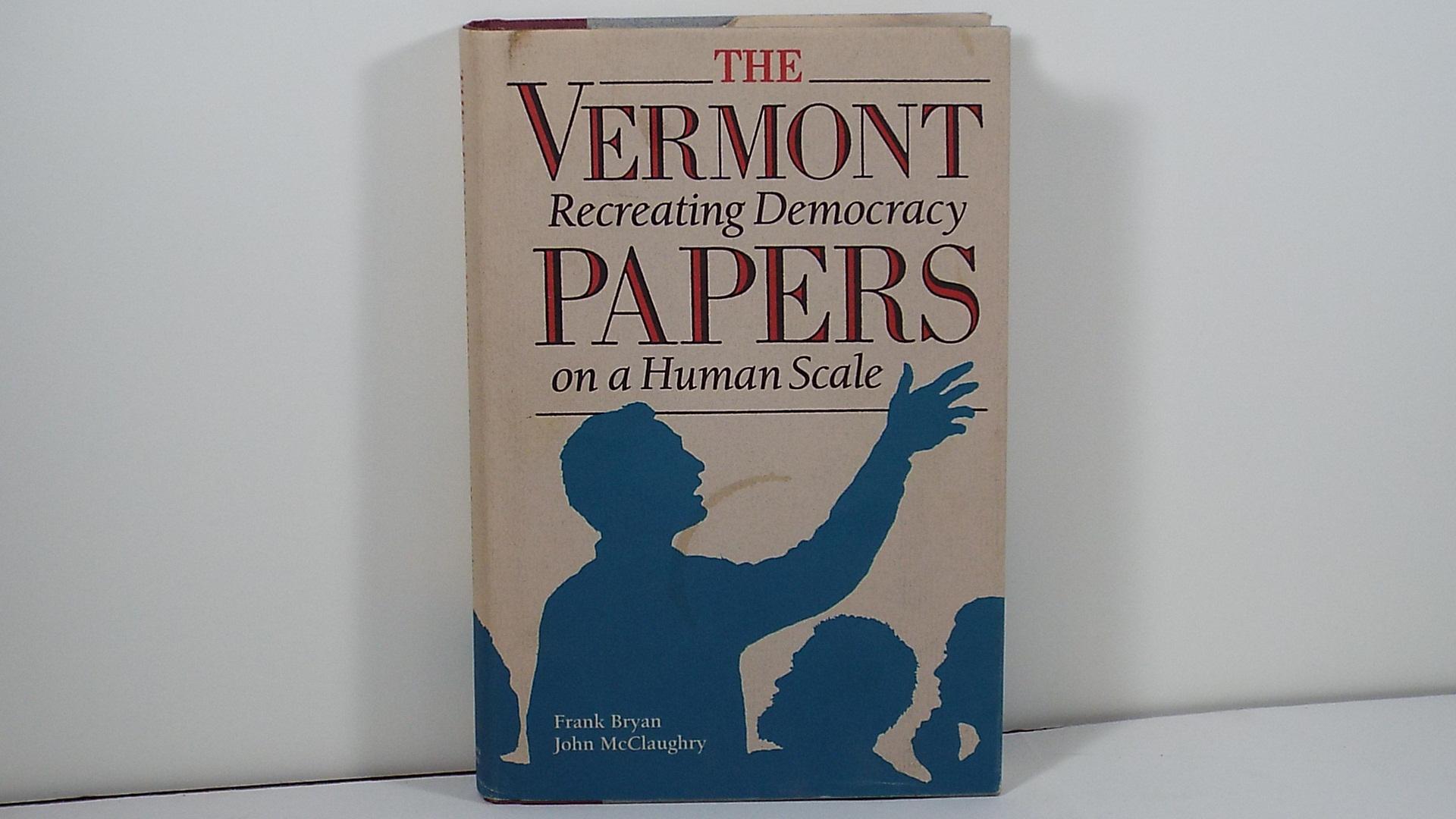

Thirty years ago this month, Chelsea Green Press in White River Junction published our book, The Vermont Papers: Recreating Democracy on a Human Scale. We dedicated it to “the memory of Ethan Allen and all those hardscrabble Vermonters who, in his tradition, and through their cussedness and liberal vision, have worked to preserve real democracy in Vermont for over 200 years.”

Our thesis was original. Like many others, we cherished the Vermont tradition of liberty, spelled out so beautifully in our 1777 Constitution, and of democracy, originating with our town meetings brought here by our earliest New England settlers. But we took the argument further. We said that Vermont of 1989 had “leapfrogged America’s urban-industrial period and landed smack in the Information Age … Vermont is still a governable place … Vermont matters most because it is small, not in spite of it.”

“For Vermont, with its tiny state capital, with its town meetings, its citizen Legislature, its two-year term for governor, has preserved the institutions and traditions of liberty and community … and has a rare opportunity to breathe new life into its democracy, (and in doing so) demonstrate how the rest of America might learn to recreate its own.”

We took a long look at how Vermont was governed. Then, and now, there are nine incorporated cities and 237 towns. Beginning in 1965, when welfare was taken away from town overseers of the poor and lodged in a state agency, the Legislature has steadily removed functions from the town level to the state level.

In addition, the state was beset by planners, frequently recent imports, who believed central planning was essential to keep ordinary people from ruining the dream of making Vermont The Perfect Little State. Gov. Madeleine Kunin won the support of these Pretty People, as we called them, by promising in 1987 to bring Vermonters into a “new planning era,” where nothing of any consequence happens unless provided for in the plan — “uniform in standard, specific in requirements and tough on delinquents.” (Act 200).

The Grand Solution was — what else? — centralization, of a little state that, by some political science assessments, was the least centralized state in the union. These enthusiasts had a clear idea who would be in charge of the vastly amplified state — their own better-educated, more experienced and more high-minded selves — certainly not ordinary, short-sighted, bumbling Vermonters who would be their subjects. The freemen and women who would, paraphrasing Ethan Allen’s rallying cry, “confound and rebuke the forces of centralism,” were disorganized and seriously overrun.

We saw that merely restoring most state functions of 1989 back to the towns was no longer possible. Our solution was to revitalize Vermont democracy by creating full-blooded local units of government close to the people, yet large enough to muster the competence and resources to bring back much of what the state had taken away from them, and govern democratically according to the traditions, wishes and genius of their communities.

To us, “local” should mean more than little squares and diamonds laid out in a wilderness by 18th-century surveyors. Rather, it would include some 40 cohesive larger units that we called by an old English name, shires. (These would replace the 14 counties that now exist but have no social coherence and little, if any, power.) In our view, a typical shire would have a shire moot, a citizen assembly like Brattleboro’s representative town meeting. Its elected members would choose a shire council, that would supervise the civic affairs of the shire through a shire manager.

The state would continue to manage certain large-scale functions, like major highways, air and water pollution, the legal system, federal-state relations, and the protection of civil rights and liberties. The shire would be responsible for all of the functions of municipalities not retained at the state level, especially the “people functions” such as education, health and welfare. Shire finances would be built on tax-base equalization from the state level, like the Canadian revenue sharing system in effect since 1957.

We placed a lot of emphasis on promoting what might be called “Shire identity,” or indeed, patriotism. Each shire would have its flag, public ceremonies, athletic teams, resource exchanges, charities and even its militia (most likely a volunteer fire and medical unit.) We hoped people would come to give their allegiance to the shire as their primary community, even though a shire moot could always create sub-units to deal with even more local concerns.

The final third of the book was devoted to recreating at the shire level programs for human services, education, agriculture and land-use management. Even 30 years afterwards, we are confident students of public policy will still find many useful proposals and real-world examples in those pages.

The Vermont Papers was well received. Senator and former Oregon Gov. Mark Hatfield wrote “this thoughtful and challenging book ought to be read by all those who have a stake in our government — all the citizens of this country.” On the right, National Review’s Joe Sobran and, on the left, The Nation’s Kirkpatrick Sale had kind words. The Boston Globe’s reviewer said “The Vermont Papers is one of the most original political economic analyses ever written about New England.”

Even former Gov. Philip Hoff, the epitome of an arch-centralizer, was kind enough to say he would “like to make this book required reading by Vermonters.” And socialist Mayor Bernie Sanders of Burlington said he “highly recommended this book,” because “we need radical new ideas if we are going to retain in Vermont the spirit of democracy and citizen participation that many of us treasure.” (When one of us, in the State House cafeteria, went up to the mayor and said “thanks for writing the blurb for our book,” Sanders grunted “didn’t do it for you. Did it for Frank.”) Perhaps the funniest observation came from a Dartmouth professor, who observed “the authors’ map of the shires looked like a phrenologist’s map of the head.”

Kind words aside, the real question was, did The Vermont Papers gain enough traction to influence events in Vermont? The answer is no. The centralizers marched bravely on down their shining path, and the champions of the “local,” historically suspicious of any entity above the town level as pernicious regionalization, did not flock to our banner.

So where has Vermont gone since 1989? Under both Republican and Democratic governors, the state has steadily assumed more control of Vermonters’ lives, and notably caused more fragmentation of governance beneath the state level. Waste management became a regional district function in 1987. Act 60 of 1997 made public education a state function, and Act 46 of 2015 crowned a hundred years of efforts by educrats to create unified school districts beyond the control of local voters, taxpayers and parents. These unified mega-districts are doomed to be controlled by the Agency of Education, its superintendent commissars and, of course, the teachers’ union.

The centralized public welfare system, created in 1965, has solidified its grasp of “the poor.” That’s because its regional administrators must conform to exhaustive federal requirements, and can find no time or space to mobilize local communities in support of aiding their poor to move up to better things. Green Mountain Care — the remnant of the failed single-payer system that Governor Shumlin abandoned in 2014 — is converting itself into “All Payer,” whereby one giant Accountable Care Organization gradually controls the finances and services of all the health-care providers, shuts down the inefficient ones, and rations care to stay within its state-determined budget.

The state Legislature, long one of the nation’s most citizen-responsive, is also changing, and not for the better. Unlike earlier days, when party lines were far more fluid, legislators of the current majority party in the House are dragooned into casting votes for the “leadership” position, or else cast into the outer darkness (along with the minority). Last year, the Ethan Allen Institute identified 42 registered lobbyists for environmental and “climate change” legislation, not counting those for whom that issue was a secondary interest. By contrast, aside from a few representing heating and motor fuel interests, there is no lobbyist for the interests of ordinary Vermonters who will ultimately have to pay for those ambitious “climate change” schemes.

And finally, the cherished Vermont town meeting tradition, our claim to democracy, is under serious pressure. More and more towns are switching to Australian ballot. Of the towns that retain meetings, more and more of the town business is strait-jacketed by federal and state requirements, and conditions on federal and state funds. With school meetings taken away to unified districts built on the waste management district model that few besides self-interested parties are likely to attend, town meetings will shrink down to electing town officers (mostly uncontested), managing town roads, deciding occasional capital investments and renewing acquaintances.

Alas, despite the hopeful subtitle of The Vermont Papers, Vermont has not been “recreating democracy on a human scale.” To the contrary, we are moving toward a plebiscitarian democracy of annual or biennial visits to the Australian Ballot Box, polls open from 10 to 7.

All in all, mark The Vermont Papers down as a brave if idealistic attempt to chart the beginning of a campaign to preserve and refresh liberty, community and democracy in the one small state best suited for such a revival. But now the times are changing in the direction of decentralism and democracy. The “assembly line” mentality of urban industrialism has been replaced by the “personal computer” mentality of post industrialism. “State of the art” information is as available to a citizen sitting in a town meeting in the smallest of Vermont towns, as it is to a member of the United States Senate in Washington, D.C.

Wrote the one reviewer on Amazon.com: “I am in the middle of re-reading this prescient book after having found a new old-stock copy. This should be required reading for any high school civics class — if there are still civics classes.” (5 Stars)

Man, I remember when I first picked up an old, dog-eared copy of The Vermont Papers; it was probably around 2005, and I was just at that time beginning to make the intellectual turn in my thinking about community toward localism, participatory democracy, and the like. It was a crazy, wonderful, challenging trip through local government re-imagined on the most practical of fields: state government. I still have the book on my shelf, and still find inspiration in its Shire models. A salute to you, Mr. McClaughry, for helping to bring your ideas to print, however ignored you feel they may have been.

I note, though, that sometimes ideas are ignored because they no longer match the moment, or the needs of the people participating in crafting their future. I further note that this essay was authored by only one of the two authors of the book, and that the other author, Dr. Bryan, might take issue with some of what is written here. For example, Mr. McClaughry, you invite us to commiserate with you about the terrible fate of Vermont being subject to the rule of “42 registered lobbyists for environmental and ‘climate change’ legislation,” who ignore that wishes of “ordinary Vermonters who will ultimately have to pay for those ambitious ‘climate change’ schemes” (by the way, impressive use of scare quotes, there). However, Dr. Bryan, here, expresses a slightly different message: “Environmental protection can’t be local. The Connecticut River is a great example there: The river is owned by New Hampshire, but really it should be controlled by New England, at least, so that’s a bad boundary. Some things cannot be administered at the local level and should not be. And the key is figuring that out. Unwrapping it.” To be sure, there is no reason to believe that Dr. Berry’s acknowledgement of some limits to localism means that he would be total agreement with whatever proposed climate change responses are being circulated around Montpelier–but it might, at least, mean that were he to weigh in on this piece, some acknowledgement of the things we know now, that were not known in 1989, would be in order.

Centralism will continue as long as we have a money economy.

Insightful article, and I look forward to reading the book. I’ve seen something similar in my home state if Utah, but here it’s happening from the bottom up. Traditionally, politics hinged on local committees and community caucuses, and people grew where they were planted. This is still true in many rural parts of the state. But now, the Wasatch Front, the cities within 50 miles of the state capital Salt Lake, operate as a single cultural blob, and people drift around the blob according to the winds of the job and real estate markets. Members of generation are no longer “from” anywhere, they just “live” there. Few cities have maintained a local political identity; Provo is one of them.

Decentralization is coming, inevitably, because the only ideas the centralizers have now are stupid, unpopular, and most importantly of all, completely unaffordable. For example, they’re several decades too late to pass any sort of “single payer” silliness (which would be unconstitutional anyway). There’s no money left.

It’s far better to have political power than money. The “deal” (though it was unwilling, and forced on them) smaller regions made in that direction in the last 50 years was a disaster. Unwinding that will be difficult, but there’s no other option, so it will happen.

Brian and I disagree about most things, and his comment here is no exception (specifically, I would dispute basically every claim his makes in his first paragraph), but I think his final sentence is completely correct–the unwinding of the sovereign, centralized, liberal capitalist state is inevitable. I almost certainly see it happening in a very different way than he, and my reasoning as to why “there’s no other option” is likely very different as well, but I’m in the same boat has he (just on the far left side). My children and grandchildren, like his, will almost certainly see the United States of America develop an entirely different social contract, or replaced by an entirely different kind of state entirely.

“Brian and I disagree about most things”

Hey now I think that’s an exaggeration. I think on ends we mostly agree–small & local is better than the alternative, in general. On means, yes, we often/usually disagree. I say the way to strengthen local communities is to give them (back) political power, and you seem to generally disagree. That’s ok, I am quite confident it’s going to happen, because the alternative (closer to your way than mine) has been tried for the past 50+ years and is a proven failure, and is (we agree!) completely unsustainable and headed for collapse even in the fairly short term. Once political power is disbursed again, then whether a small town wants to promote strong unions, or cooperatives, or atomized individuals, can be properly decided by its residents, but in the current situation where they have been reduced to wards of larger entities, those debates are completely forestalled.

Comments are closed.