Aberdeen, SD. As the title implies, Gillis J. Harp’s Protestants and American Conservatism: A Short History purports to be a treatment of how these two separable concepts, Protestantism and political conservatism, have in their combination made a unique imprint on the American political tradition. Harp, an historian at Grove City College, has produced a fine work that is more than simply an exercise in antiquarianism. Any reader who is basically familiar with current debates on religion, conservatism, and the nature of the Republic cannot but see today’s tensions within political and religious conservatism mirrored in Harp’s text. To put it succinctly, the Ahmari-French debate has deep antecedents in American history (for those not familiar with the debate, you might begin by looking here and here). It is a compliment to Harp’s well-researched and highly readable volume that one cannot help but reflect on its current relevance.

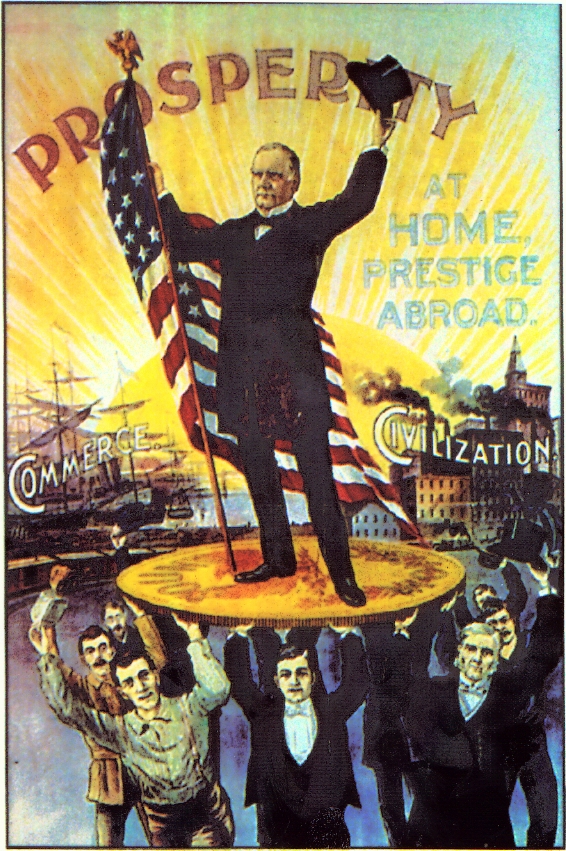

What Harp unfolds over the course of this work is a shift in politically conservative Protestantism from being a check upon the liberal notions of individualism and freedom to heralding such liberal concepts as Biblically sanctioned. The conservative Protestant strain of American belief went from being a “check on an individualistic and competitive impulse,” particularly in the colonial era, to an “unqualified endorsement of individualism and competitive market forces” in the 20th century. This eventual destination of conservative Protestants has strained Protestantism because the enthusiastic endorsement of the American project, including libertarian conceptions of government and economics, remains at odds with aspects of the Protestant tradition.

Early American Puritans would find odd such a validation of libertarianism, to say the least. Gillis notes the first-generation Puritans stressed the symbiosis of church and government, with the government serving God by enforcing the Puritan moral code. While it would be a mistake to describe this relationship as theocratic, as in general neither government nor church officially participated in the other institution, Puritans understood that government existed to promote religion while the church held a kind of pride of place. Calling to mind Sohrab Ahmari’s critique of “transgender story hour” at libraries, Harp quotes a summation by scholars Perry Miller and Thomas Herbert Johnson to the effect that Puritans “would have expected the rule of ‘laissez-faire’ to result in a reign of rapine and horror. The state to them was an active instrument of leadership, discipline, and wherever necessary, of coercion.” The Puritan covenantal theology did not see human beings as isolated individuals seeking private goods, but rather as communal beings working for a common good. The first weakening of the communal conception of the good comes with the Great Awakening and its emphasis on an individual and emotional experience of God.

Harp considers in detail the religious views of Loyalists who dissented from the American Revolution. He finds in this surprisingly large group commitments to the authority of religious and political leaders rather than an emphasis on consent; a rejection of Lockean social contract theory and that theory’s philosophical individualism; the value of obedience over individual conscience; and “the importance of social unity and order” rather than individual expression. It is within this era that one begins to see the rise of a more secular conservatism, with John Adams held up as Harp’s exemplar of such a mindset. Adams shared many of the same goals as conservative Protestants, namely the importance of morality to a functioning democracy, but justified his views in non-religious terms. For Adams, religion performs a useful social function of maintaining order, but Adams was unconcerned with theological justifications of religion’s authority in this arena. Adams prefigured Dwight Eisenhower’s admonition that America needs religion, but Eisenhower was not particular as to which one. High Federalists, such as George Washington, “were not especially orthodox” and “focused on the political and social function of religion, rather than its intrinsic truth or ultimate validity” (emphasis in original).

In particular, it is in the post-Civil War Gilded Age that Harp sees a fundamental shift in political conservatism’s commitments. The philanthropist industrialist Andrew Carnegie and sociologist William Graham Sumner are harbingers of a new conservatism. Skeptical regarding the ability of the central state to promote virtue, these thinkers critiqued the notion of a publicly supported common good, leaving it to private charity and private initiative to work out any troubles that faced the nation. Sumner in particular adhered to a central modern tenant, the idea of progress. He simply thought that progress would arise from the unplanned decisions of millions of unencumbered Americans. Trusting in the benevolence of private man, Sumner distrusted any public attempts to encourage virtue. While not sharing Sumner’s more secular view, Old School Presbyterians took a similarly individualistic view of human nature and became advocates for a minimalist state: “Their intense individualism now conceived of government as the primary threat to individual liberty.”

This view was not without its Protestant critics. Yale’s Noah Porter held to the more communal, organic view of the political society. “It may be well to repeat the truth, that the state is from its very nature an organism; that is, a society constituted for and maintained by certain functions, which it can perform through certain organs … for the well-being of the state.” Similarly, G.J.A. Coulson argued that “society is therefore not a combination for the conservation of rights, but a combination rather for the enforcement of duties.”

But the voices of those such as Porter and Coulson were fading from view. By the early 20th century, “With the virtual disappearance of more traditionalist forms, the classical liberal conservatism that had emerged during the Gilded Age soon became the main public face of American conservatism.” By mid-century the traditionalist Protestant intellectuals who had done so much to define conservative Protestantism in America were not to be found, replaced instead by populist pastors and television personalities. Harp connects this trend with the overall decline in public intellectuals and a concomitant rise in anti-intellectualism amongst conservative Protestants. Another explanation he does not consider is that by the middle and late 20th century the commanding heights of American culture, namely education, entertainment, and journalism, were increasingly closed off to Christians of a traditionalist bent. The story is not just of conservative Christians abandoning intellectualism, though no doubt that is true as Mark Noll has argued. It is also a story of a rising contempt for traditional Christianity by America’s cultural and political elite.

What Harp finds is that ironically it is Catholic thinkers who maintain the Christian communitarian argument once articulated by conservative Protestants. This echoes the currents of today when many of the leading lights of post-liberal thought are Catholics such as Sohrab Ahmari, C.C. Pecknold, Patrick Deneen, and Adrian Vermeule, recently given policy chops by Catholic United States Senator Marco Rubio. This stands in stark contrast to the late-20th century movement in conservative Protestantism to baptize classical liberalism and identify the American tradition with Christianity in a way that tended to distort both.

The aforementioned Patrick Deneen has spoken of an “alternative tradition” in American history. This tradition is largely what Harp is associating with traditional conservative Protestantism up to the late-19th century. For those who are skeptical of today’s rampant individualism with its emphasis on autonomy and self-creation, the American tradition offers just such an alternative. More communally minded, less skeptical of government, with a commitment to thick, meaningful society, there is much to draw upon. Harp notes the dissent from the 20th century libertarian conception of the state and the human person among some Reformed Protestants arguing from the Kuyperian tradition. Both Protestants and Catholics have much to learn from this strain of political theology.

While Harp’s book is deeply valuable, I’d be remiss if I didn’t offer a few criticisms. First, Harp seems to lack appreciation for the virtues of federalism. Criticisms of the rise of the central state in late 19th and early 20th century America do not necessarily mean an endorsement of the minimalist, libertarian state. As I have argued elsewhere, Christians are right to be cautious in endorsing nationalism. Instead, the kind of common good conservatism (or capitalism, if you will) that is attractive to many post-liberals and Front Porchers is more likely to thrive with a decentralized government devolving responsibility to local communities. Indeed, it is the argument of many, from Alexis de Tocqueville through Marvin Olasky and Charles Murray, that the centralized nation state is the enemy of vibrant local civil society. Prof. Harp may be in complete agreement with me here, but some indication of these distinctions would be welcome.

Further, in discussing the rise of the “Religious Right” in the late-20th century, Harp goes into some detail on the thought of Rousas Rushdoony. One would have thought that the specter of Rushdoony was interred years ago by Ross Douthat, but here he is rising from the grave to haunt us yet again. The fact that Gillis does not name a single significant figure on the Right actually influenced by Rushdoony might be an indication that his influence is largely in the imagination of the Religious Right’s political opponents. The closest Harp comes to noting any Rushdoony influence is through an allusion to Glenn Beck, who, as a Mormon, is a poor example in a book ostensibly about conservative Protestants.

Finally, the book’s conclusion considers the (in)famous Evangelical support for Donald Trump. Like many, Harp expresses some perplexity (or is it frustration?) that 81% of white Evangelical voters supported Donald Trump in 2016. This, Harp explains, might stem from an historical religious-conservative deference toward authority, i.e., they are easy pickings for authoritarians. This analysis calls out for the more nuanced take exemplified by Tim Carney’s Alienated America. While Harp ponders why religious conservatives did not support one of their own, such as Ted Cruz, for the Republican nomination, Carney ably shows that they did support religious conservatives. Carney marshals troves of data to show that Trump’s support in the Republican party was weakest amongst its most religious voters, with Mormons in Utah and Reformed Christians in Iowa being good examples. The strong conservative Christian support for Trump arose after the nomination. That itself requires a more searching analysis than is provided by Harp. As Carney and others have noted, that 81% contains some who are enthusiastic about Trump, but also many who “held their noses” and voted for him despite Trump’s many offenses against Christian morality and theology. To understand this overwhelming support for Trump one might ask what attracts voters to Trump. Yet, just as importantly one might ask what repels these voters from the Democratic party (and Hillary Clinton in particular) that they would vote for the vulgarian Trump rather than any Democrat. It isn’t just what is “right” about Trump (from the point of view of these voters), but what is “wrong” with the Democrats.

I am being too hard on Prof. Harp as my criticisms amount to quibbles regarding an otherwise outstanding book. Protestants and American Conservatism reveals a capacious knowledge of American religious history. Harp’s lively, readable explication of this history commends it to the attention of those interested in American history, especially American religious, intellectual, and political history. Those who tend to side with Sohrab Ahmari and the post-liberal critics of viewpoint neutrality can find copious support within the American political tradition, dating back to that tradition’s very origins. As skeptics of the liberal order slowly work out a positive vision for the republic, they now know that they have forebears from which to learn, both in their success and defeats. May we learn well.

Thank you for the review. Sounds like it could be a very interesting and illuminating book. Unfortunately your caveats about the coverage of the last few decades makes it sound probably not worth reading. “Protestants” and “American Conservatism” are both such hugely broad and constantly evolving topics that if an author can’t even get the events that we’ve lived through right, how can he be trusted to discuss the more distant past with any accuracy?

My sincere thanks to Jon Schaff for his thoughtful and generous review of my book. Allow me to respond briefly to some of Prof. Schaff’s perceptive criticisms.

First, evangelicals clearly were ostracized by increasingly secular elites during the twentieth century. I believe I did observe that their isolation (particularly in the wake of the Scopes Trial) wasn’t only the product of evangelical anti-intellectualism.

Second, Schaff’s point about the federalist dimension of the American system is an interesting one and something that might have benefited from more attention. Of course, localism has historically been used for mixed reasons — including defending Jim Crow. But this dimension is worth further exploration.

Third, I agree with Schaff that Rushdoony’s influence has been exaggerated by some commentators eager to caricature conservative Protestants. Still, I thought it important to spend a few pages on Rushdoony since his intellectual project was just the sort of thing that represented the central subject of my study. By the way, I did mention his influence (via Gary North) on Pat Robertson. North was the conduit for Rushdoony’s economics for some libertarian-minded evangelicals.

Finally, my treatment of the 2016 presidential contest was intentionally relegated to a brief section at the end of the book. As an historian, I’m not sure I’m equipped to draw definitive conclusions about the meaning of events so recent. Schaff stresses that many white evangelicals voted for Trump with considerable misgivings. Yet, I do wonder how serious those misgivings were, given their persistent, apparently undiminished support for Trump in the years since his election. Further, more could certainly be said about how the Democratic party has managed to alienate people of faith. Given that the primary focus of my book was on American conservatism, I trust that relative neglect is excusable.

Comments are closed.