Nampa, ID. According to Ross Douthat, American culture is a decadent one, but “decadence” is not what you think it is. As suggested by the cover of the book, the word decadence turns our minds to images of over-indulgence in pleasure and luxury, but Douthat highlights an older meaning of decadence as simply being a matter of cultural or civilizational decline. That decline may include excessive indulgence and moral decay, to be sure, but it is not limited to that moral decline.

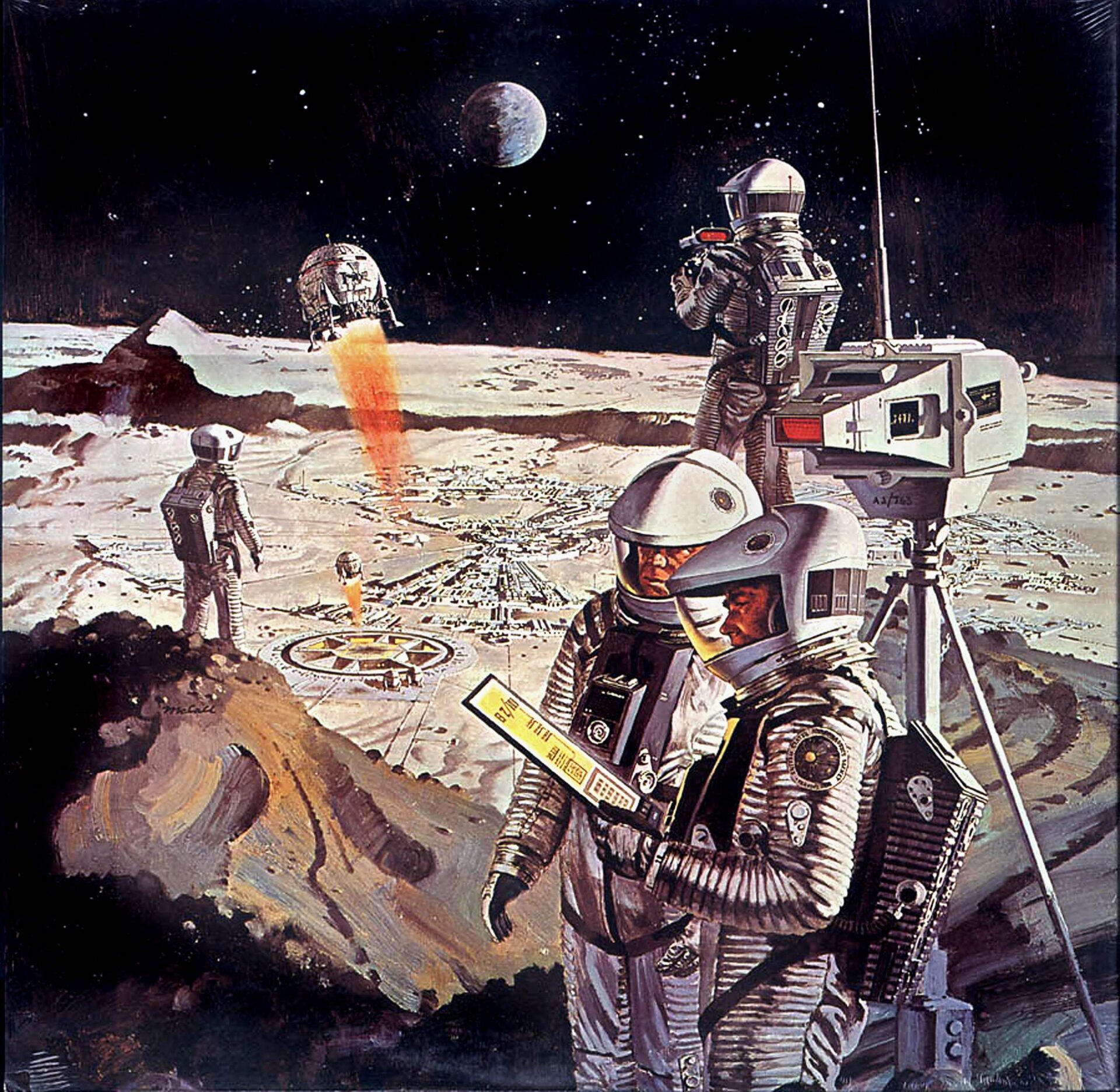

Douthat uses space travel as something of a thematic example of this decadence throughout the book. He begins with the 1969 moon landing, what he calls “the peak of human accomplishment and daring, the greatest single triumph of modern science and government and industry, the most extraordinary endeavor of the American age in modern history.” He speaks wistfully of all of the expectations for the future that the landing awoke in our collective imaginations—bases on the moon, flying cars, colonizing the stars—imaginations that found pervasive expression throughout pop culture. He then contrasts that hopeful imagination with the failure to accomplish any of it. While we have perfected and refined much of what we then accomplished, we haven’t really gotten any further. There is no longer that hopeful expectation of reaching the stars.

For Douthat, this is but one example of our entire cultural moment. This is what our decadence is defined by: the cessation of hopeful forward movement. Somewhere in the midcentury we arrived at a place of great accomplishment—culturally, politically, economically—and then we stopped progressing. We’re just sort of stuck, with no sense of where to go.

The first section of the book explores this phenomenon under four headings: stagnation, sterility, sclerosis, and repetition. He describes stagnation as our failure to progress technologically and economically; sterility as our failure to embrace marriage, babies, and the attendant relationships; sclerosis as our inability to get anything done or make any progress politically; and repetition as the tendency of our culture simply to recycle and repeat itself, illustrated by popular culture generating endless reboots of well-worn franchises.

I want to be very clear up front: whatever criticisms I may have of the book, Douthat’s descriptive project is wise and full of insight. At the same time, however, each descriptive diagnosis has a frustrating tendency to neglect possible questions that might be raised in response.

As one example, consider his description of stagnation, by which he refers to our failure in recent decades to make any decisive economic or technological progress. He describes the oft-cited idea that a time traveler from 1890 appearing in 1950 would find just about everything radically new—the refrigeration, the communication devices, the modes of transportation. But a traveler from 1950 appearing in our own time would recognize just about everything. To be sure, each cultural artifact is more technologically advanced, but the basic concepts of phones, vehicles, and appliances are still in place. The internet is perhaps the primary outlier, but by way of a rhetorical move that Douthat makes repeatedly throughout the book, he would point out that it’s something of an exception that proves the rule. Even the internet illustrates our stagnation by way of being an outlier (where are all the other advances we’ve been expecting?) and by the way in which it is used (pornography and gaming and businesses like Uber that continue to disappoint by way of failing to actually make a profit).

On the one hand, this sort of observation, multiplied many times over throughout the book, is incisive and perceptive, observing and describing trends that it can be easy to miss. In fact, I should emphasize at this point that a summary of his thesis really can’t do it justice; the cumulative effect of the chapters and illustrations and arguments is powerful and persuasive, with something of a literary and even artistic flair to it all. The book is written well enough to reward a cover-to-cover reading.

On the other hand, there are some questions that this example raises. Why treat the development of technology from 1890 to 1950 as the standard by which to judge a particular half-century period? Is it really the norm? It seems to me that just about any other 60-year period in all of human history would fail by the same standard. What that illustrates is that perhaps the midcentury period was the real outlier. That rate of technological change and progress simply isn’t normal.

Douthat makes the same sorts of observations with regard to the politics of the midcentury, arguing that much of the great political accomplishments of that era have given way to polarization and gridlock, to elections that swing back and forth ideologically with changes only really being accomplished at the margins, and often unsustainably. For Douthat, the Obama presidency is the perfect example of decadent politics. After the passing over the Affordable Care Act, which was itself really just a matter of incremental change at the margins, Republican resistance made it impossible for Obama to do much of anything. Domestic policy was accomplished by executive order—later easily undone by another president—and foreign policy was summed up by his oft-quoted “don’t do stupid shit.”

Here I would express the same question as before: while this description of our current moment is insightful, is it really warranted to critique our time by way of comparison to the midcentury period? What if that time was unique? Douthat’s thesis seems to depend on a sort of nostalgia for an earlier time, a nostalgia that may not be entirely warranted.

One of the reasons I recommend reading Douthat’s book is that his descriptive project led—at least in my own mind—to those sorts of conclusions about how we should live in a time of decadence—resisting the time’s worst impulses, taking advantage of its benefits, and focusing on the local, the ordinary, the human scale. As I read the book, feeling burdened by the frequent and painful accuracy of his descriptions, I looked forward to that positive move, glancing ahead to chapter titles like “Giving Decadence Its Due” and “Renaissance.” The book failed, however, to deliver that hopeful way forward, and while I grant that Douthat may have purposeful reasons for that move, it nevertheless disappointed.

In the middle section of the book, Douthat argues for what he calls the sustainability of decadence. Indeed, the greatest danger of decadence is not that it will end with cataclysm, with apocalypse and barbarians, but that the barbarians will never arrive, that decadence will simply perpetuate itself endlessly and pointlessly. He describes our escape into opioids and computer games, to a life of the virtual that avoids actually doing or accomplishing anything. And he describes a movement toward what he calls a “kindly despotism,” a converging of technology, government, and corporations that will keep us safe while whittling away at our privacy and freedoms. Douthat’s description is not of the terrors of 1984 but of a brave new world in which we are already living, a surveillance state that we have freely embraced for the sake of safety.

Despite that sustainability, Douthat does point forward to three different ways that decadence might end: catastrophe, renaissance, and providence. Perhaps climate change or a pandemic or mass migration will lead to the collapse of the current order. Or, conversely, perhaps there could be revival of spiritual fervor that would invest Western culture with a newfound sense of meaning and energy and purpose.

Interestingly, while Douthat entertains many possibilities for how our sustainable decadence might end, he offers compelling counterarguments for all of them, concluding with a chapter entitled “Providence.”

“But I would be a poor Christian,” he writes, “if I did not conclude by noting that no civilization—not ours, not any—has thrived without a confidence that there was more to the human story than just the material world as we understand it.” He ends on this note, suggesting that the only way forward might be some sort of divine intervention in world history. “If we have lost that confidence in our own age, if the liberal dream of progress no less than its Christian antecedent has succumbed to a corrosive skepticism, then perhaps it is because we have reached the end of our own capacities at this stage of our history, and we need something else, something extra, that really can come only from outside our present frame of reference.”

I, like Douthat, am a Christian, and yet I find this a strange note on which to end the book. The Christian conviction is that the “Something Else” (to which Douthat later refers with similarly capitalized letters) has already acted decisively in history by way of the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Jesus. He says he would “be a poor Christian” if he did not point to the need for more than the material world. He is correct, and I’m grateful for his explicit turn in this direction. But in a similar manner, I would be a poor Protestant Christian if I did not highlight the ancient words of the Hebrew scriptures, in which the Creator declared the creation “very good,” and if I did not point out that the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus declared the Creator’s intention to restore the life of that good creation. While the Christian looks forward to the future in which the Creator will set all things right, the life of the world in the here and now remains good and meaningful.

In other words, Douthat and I have precisely Christian reasons to affirm the goodness of life in this world, and to do so with gratitude, even within a decadently stagnant society. We have precisely Christian reasons to turn our imaginations in a different direction, because the Christian faith clearly affirms the goodness of the very ordinary things of ordinary life, even—or perhaps especially—on a very small and local scale.

As an example, what if the wisely diagnosed sclerosis of our national political institutions is simply an opportunity to turn our focus local, where it should arguably have been all along? This is Levin’s argument in The Fractured Republic, and I think it deserves more attention as a conclusion to be drawn from Douthat’s descriptive project. On this telling, decadent national politics does not lead us to the conclusion of despair or waiting for barbarians or hoping for divine intervention. Instead it leads to somewhere far more optimistic and local: join a community group, run for city council, serve on a civic board, contribute to the downtown association.

It is these sorts of mediating institutions that best serve human flourishing and that protect against the “kindly despotism” that Douthat rightly warns us against. And it seems to me that there is a hopeful way of describing national political paralysis as an opportunity, a catalyst for that sort of local turn.

Likewise, what about all the opportunities for local life on a human scale, opportunities afforded by much of the prosperity described by Douthat as being decadent? To be sure, if we focus on overall cultural trends, we can observe a sort of stagnation and sclerosis, even a despairing decadence. But when we look local, when we look at the particular lives and people around us, we can often see something different.

At one point in what I think is the weakest chapter of the book (“Giving Decadence Its Due”), Douthat somewhat snarkily acknowledges the objection, “I suppose you want to bring back smallpox . . . I bet you miss the plague.” He considers such an objection to be condescending, a voice that will always be there “smug to the very last, if our dystopian elements become more universal but our wealth and stability remain.”

I must confess that I am entirely perplexed by this easy dismissal of the objection. Indeed, I’m inclined to hazard being accused of being smug and condescending, and press the question: “do you want to bring back smallpox?” There is no time period in history in which I would rather live. And it seems to me that this general sense of things demands a bit more respect. It’s true that we don’t yet have a colony on Mars. But countless people are living very ordinary lives and doing very ordinary things that are true, good, and beautiful.

Is spaceflight really the measure of a society’s success? What about the kind and competent medical care that my son received after wrecking his bike? From the primary care doctor’s immediate provision of a splint, to the bizarre affordability of his pain medications, to the warmth and kindness of the radiology technicians, to the very human yet highly-technical proficiency of the orthopedic specialist, all of it by way of leading to a full recovery from a (visually horrifying) spiral fracture—if this is decadence, I’d like to keep it around.

Or what about the proliferation in local and craft culture and businesses, described compelling and optimistically in Richard Ocejo’s Masters of Craft? Or, extremely anecdotally, what about the surge of interest in board games? I mention this precisely as a way of defying the emphasis on grand cultural pursuits on the scale of a moon-landing. In his excellent Digital Minimalism, Cal Newport describes and promotes a kind of backlash against the digital decadence that Douthat wisely diagnoses. Board games are a fascinating example of this—the turn toward the physical and tactile, the embrace of more in-person and human ways of interacting with others.

What I’m wanting to argue is that much of what Douthat describes as decadence creates the space and opportunity for a turn toward the local in politics, community, and culture. He wisely and helpfully identifies all sorts of trends that we ought to recognize and resist. But rather than despair, one might even celebrate the newfound clarity toward which his book directs us. Ordinary and small work in an ordinary and small place just is good. It doesn’t need to get us to Mars. It simply needs to be a means of serving God and loving your neighbor as yourself.

This is a wonderful push-back against a thesis that includes a lot of truth, but which is also itself, as Damon Linker observed, ultimately kind of “decadent” as well. After all, what is more stagnate or repetitive than pointing out that past dreams of the future have not been achieved, and blaming the present for it? As cultural critique, it’s valuable; as a guide to the life we’re called to live, perhaps less so.

It is arguable that pyramids, skyscrapers, and moon landings are also a sign of decadence. Giantosarus projects are usually considered so, are they not?

As for the technological advances – – – the World War, from 1898 through 1987 (or thereabouts) is certainly a marvelous prod for tech. (War does that sort of thing).

@David: Actually, the enhancement of weapons has spurred technological innovation for centuries. For example, increasing the range of a rifle by boring its barrel in a spiral (anticipated by Hawkeye in Last of the Mohicans) led to significant advances in machine precision that improved numerous endeavors other than war.

Thanks, Nick. This is a extremely thought-provoking and necessarily rambling essay. Books that claim to present an overarching view more or less require an overarching review.

Aside from being a project that partially redirected the military-industrial-complex toward exploration rather than warfare, the moon landing had beneficial psychological and even spiritual effects that have seeped into humanity’s awareness in the past 50 years.

Should progress be viewed as a series of “triumphs” as assumed by Douthat in the quote in your second paragraph? Surely, heart transplants are a “triumph” but 19th century medical insights from Semmelweis (germ theory), Pasteur (vaccines), and Eijkman (vitamin deficiency causes disease by an absence not a presence) involved slower processes that saved more lives. And sanitation, which dates back even further, is an even less dramatic discovery that saved even more lives.

I suppose Douthat can be forgiven (or not) for ignoring the dramatic impact of cell phones on daily life in his assertion that the “basic concept” of phones hasn’t changed. I guess he was too young to have noticed the incredible leap in communications that cell phones brought. People no longer consider themselves “out of touch” for long periods each day. This “ordinary” feature of 21st century life was a quiet revolution that has permeated remote parts of the globe — here in Indonesia, the fraction of rural households that own a cell phone jumped from 8.2% in 2005 to 82.9% in 2015.

OTOH, I think he may have a point about stagnation because there seem to be fewer startups in the past decade, as well as planned obsolescence in hitech, where bells and whistles that supposedly address consumer demand become a substitute for significant innovation in a device’s capability.

Cautionary notes about technology have been published for over a century. Check out EM Forster’s story The Machine Stops (1909) about people living underground in isolation, served by machines and communicating with each other only by technology. Or Karel Capek’s play RUR (1920) about robots replacing human labor because output is measured by cost not by diligence and care.

As for the symptom of repetition, early feminists urged the study of “herstory”, a coinage that refers to looking at how ordinary people lived and died rather than focusing on famous people. Sadly, 21st century feminism seems to have forgotten this innovation and now endlessly repeats the old pattern by promoting the achievements of women who “should have been” recognized with fame long ago. What about the billions of women now alive who seek appreciation for the work they do everyday, regardless of whether a materialistic economy pays for it or not?

Martin

Comments are closed.