West Sacramento, CA. I had bought a few baseball cards when I was eight years old, mostly for the gum, but the start of fourth grade, in 1967, was when I became serious. My father had recently retired from the military and our family had moved to Rantoul, Illinois, for his new job. I was in a new school, my fifth school in five years. Mel Maxvill and I became best friends, and baseball cards are the reason why. He had hundreds of cards, some that he would bring to school to show other guys or even trade.

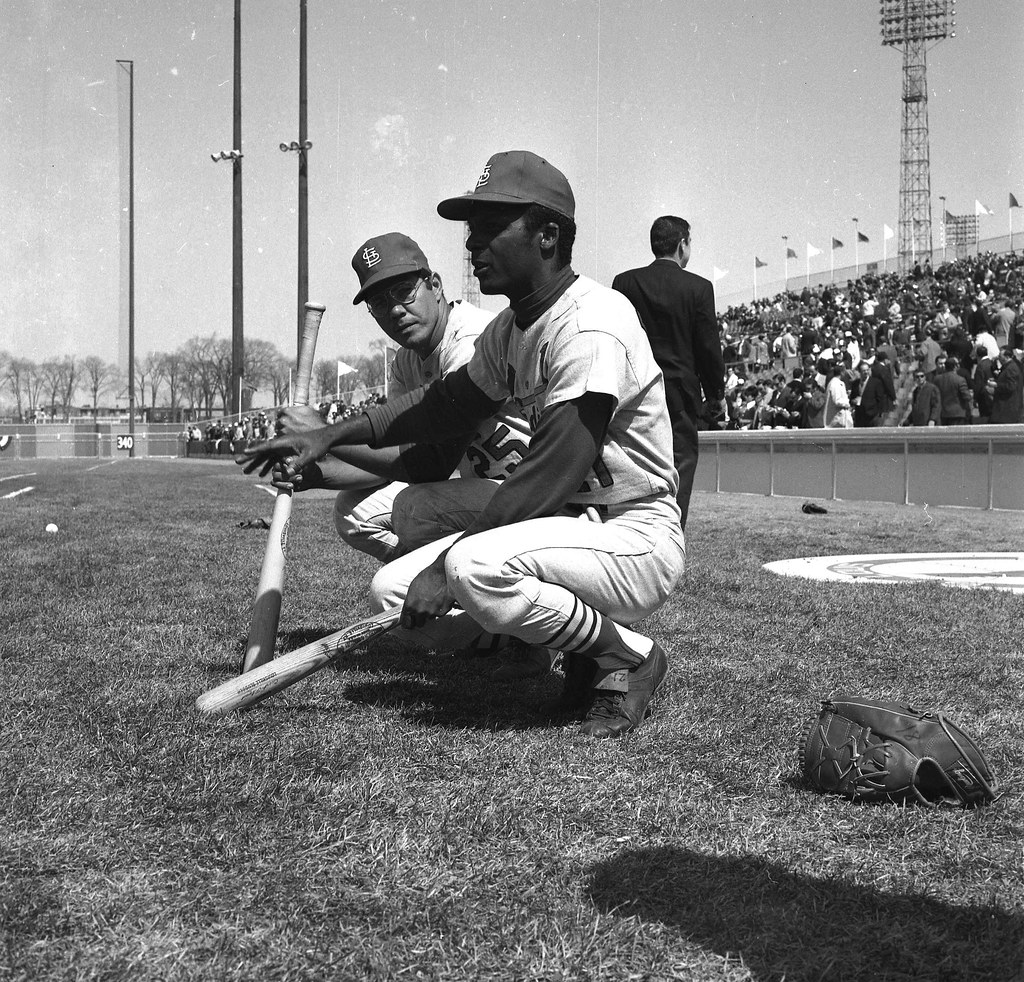

On that first day in this new school, Mel was in the hallway showing other guys his new Curt Flood, which was the best card he had bought the day before. Some guys wanted to trade him for his Curt Flood, who played on Mel’s favorite team, the St. Louis Cardinals, but Mel said he would never trade him, not for anyone.

Then some guy who was probably a sixth grader grabbed the Curt Flood card from Mel’s hand and ripped it in half, dropping the pieces on the ground. “No one wants it now,” the sixth grader said as he walked away.

Mel bent down to pick up the pieces of his card, and when he stood up I saw his eyes were wet and shiny. It looked like he was crying, and I asked him if he was alright. Mel wore glasses, and he took them off to wipe his eyes. He said he was alright, but he was also mad, and asked me why I said what I did. I told him it looked like he was crying.

“I never cried in my life,” Mel said. He was even more mad, then. “Who are you? You can’t talk to me like that.” He stared at me and said, “I’m going to show you. We’re going to fight after school. Right out front.” He pointed in the direction he meant.

I couldn’t believe it. Here I was showing some concern for another human being, and now I was going to get beat up for my trouble. I got beat up when I moved to a new school in the third grade, and now I was going to get beat up on my first day of a new school in the fourth grade. I hoped my parents were going to stop moving, or at least not make me move with them, if this is the way life was going to be from now on.

“Why do you want to fight me?”

“Because you said I was crying,” he said. “I never cry.”

“It looked like it to me,” I said. “I wasn’t making fun of you or anything.”

“I don’t cry,” he said, pointing a finger in my face. “I have allergies, and sometimes they make my eyes water.”

“I’m glad that it’s just allergies.”

“It’s too late for you to get out of this now.” He looked away from me to the other guys who were watching what was going on. “You shouldn’t have said what you said, and now we’ve got to fight.”

“Alright,” I said. I had been through this before, and I knew how to act. Plus, I knew how to make a real fist now, and throw a jab and a right hand. I didn’t know how to punch when I got beat up last year in the third grade, and that’s why I lost. At least that’s what I was telling myself.

Mel must have reconsidered, however, because near the end of the school day he came up to me and said, “Don’t ever say I’m crying again.” I told him I wouldn’t. Then he showed me more of his baseball cards. Soon, we were best friends, always comparing our cards, sometimes trading them, using our lunch money to buy more.

We got the same weekly allowance, a quarter, which was enough to buy five packs of cards at a nickel a pack. Because of sales tax you couldn’t buy all five packs at once or you would have to pay 26 cents. So, you bought three packs from one cashier and then went to another line to buy two more packs from a different cashier. I always felt uncomfortable doing this because I wasn’t sure it was completely legal and worried that before I walked out the door the store manager or someone else was going to tap me on the shoulder and tell me to come with him. I worried about it, but that didn’t stop me from doing what I was doing because how else was I going to get my five packs of cards?

I asked Mel how he had so many more cards than I did given that our financial situations were the same, and he told me would sneak away from the cafeteria once or twice a week and use his lunch money to buy cards downtown.

Woolworth’s was on Sangamon Street in downtown Rantoul and, since we had 30 cents of lunch money we would buy three packs of cards there and then cross the street and walk down a block to Ben Franklin’s, where we would buy another three packs. We would then run back to school where everyone was outside for recess and kind of slip into the crowd unnoticed.

We only did this once or twice a week because, first of all, we both liked to eat. Second, our teacher, Mrs. Briles, would send us to the principal’s office if she ever found out. Mrs. Briles liked baseball and was a big Cardinals fan. She let us listen to the World Series on the radio during school because the Cardinals were playing the Red Sox, but she was still a teacher, and Mel and I knew that teachers didn’t like kids having fun doing something they weren’t supposed to do.

I had more than Mrs. Briles to think about, though. Every time you are doing something you are not supposed to do you are worrying and always looking over your shoulder. Whether you are not paying your taxes or misappropriating your lunch money, there is always something extra to worry about.

I usually went with my dad when he ran his errands on Saturday morning, and we almost always stopped in Woolworth’s for a cherry coke. Since becoming friends with Mel, though, I wasn’t able to enjoy my coke the way I used to. I had to nervously hide my face from the cashiers, hoping nobody would remember me from during the week and rat me out.

Mel and I were better at collecting cards than we were at playing baseball, although we played catch almost every day after school, either at his house or mine. We would practice catching fly balls and grounders, making believe we were throwing a guy out at the plate or turning a double play. Neither of us could hit very well, or throw very far or fast, but we tried.

In the Little League in our town, the rules were that everyone got to play at least two innings, even the worst players. Mel and I were two inning guys. But Nicholas Shannon, our third baseman who played the whole game and was the best player on our team would always warm up with me before practice or a game. Nicholas was a year older than me, so I was proud that he always chose me to throw with.

One day, though, while we were warming before a game, another player caught a hard-thrown ball in the pocket of his glove, right in the middle where there isn’t much padding. He started jumping up and down and shaking his gloved hand in the air and moaning in pain. Nicholas laughed and said, “That’s why I always warm up with Sharp. He can’t throw hard enough to hurt your hand.”

Our lunch time expeditions for baseball cards ended in the spring of 1968 when Mel and I were caught on the playground chewing the sticks of gum that come with a pack of cards. Mrs. Briles sent us to the principal’s office and we had to clean chalkboards for a week instead of being allowed outside at recess.

The worst part of being caught, though, was that it was open house week, where the parents got to meet the teachers and talk about how their kids were doing in school. I didn’t want anyone talking about how I was doing, especially how I was doing at the principal’s office. If my dad found out about that, cleaning chalkboards was going to seem like a birthday party.

All my worrying turned out to be unnecessary, however, because not much happened. I don’t know if my mother even talked to Mrs. Briles, and I was paying attention. None of the other mothers really talked to her, either. Everyone was kind of quiet and we went home pretty early.

I didn’t know what happened and couldn’t believe my luck. I was sure Mel and I would be back buying cards at lunch in no time. On top of that, we were getting home so early that I wouldn’t have to miss “Daniel Boone,” one of my favorite TV shows. Sometimes life is just too good to be true.

And it was. I didn’t get to watch “Daniel Boone” because news reporters were on with a special bulletin. Every station had a special bulletin, all three of them. There was nothing to watch except the news about some guy named Martin Luther King, Jr., being shot and killed in Tennessee. I didn’t know who he was, but he must have been important because all the TV shows were cancelled, and the news was on every station just like when President Kennedy had been killed.

We had been renting the house where we lived when I went to Mel’s school. But my parents bought a house during the summer, and I was going to be in a new school, in a different part of town, for fifth grade. This was going to be my sixth school in six years, but I wasn’t going to move again after that until I grew up.

Going to a new school meant Mel and I would be playing our two innings each on two different baseball teams.

In the final game of the season, my team played Mel’s. We were winning 5-4 in the bottom of the last inning, when Mel came to bat with the bases loaded and two outs. I didn’t want Mel to have to make the last out, but I wanted us to win even more, so I hoped he didn’t get a hit. I didn’t want him to strike out either, especially with the bases loaded, and I hoped he hit the ball to someone other than me at second base.

I wanted him to hit the ball pretty hard, but for it still to be an out. I didn’t want to be the person who put Mel out, though, and hoped he hit the ball to the shortstop or someone else.

What Mel did, though, was strike out. He struck out with the bases loaded. We won the game, but I felt bad for him. I had struck out with the bases loaded before, and knew how it felt. You don’t want your best friend to know how it feels, too. I could tell how bad Mel felt by the way he was hanging his head and looking at the ground.

When we lined up to shake hands with the players on the other team, I could tell why Mel struck out. His allergies were bothering him again.