West Palm Beach, FL. In his new book, Yvon Chouinard recalls that, when was seventeen, he “completely rebuilt a 1940 Ford two-motor sedan and drove it from California to the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming. Across the Mojave Desert my old Ford and I purred past brand-new Buicks and Cadillacs that were pulled off to the side with their hoods up and motors steaming.” From there, Chouinard never looked back. He climbed his first mountain—in Sears Roebuck boots—and spent many of the next years of his life climbing more peaks, sleeping outdoors, and being part of the ragtag community of original “dirtbags.” Along the way, he maintained his sense of self-reliance and know-how. He began to forge his own climbing gear, which led him gradually and somewhat reluctantly into the world of business. He is now famous for being the founder of Patagonia.

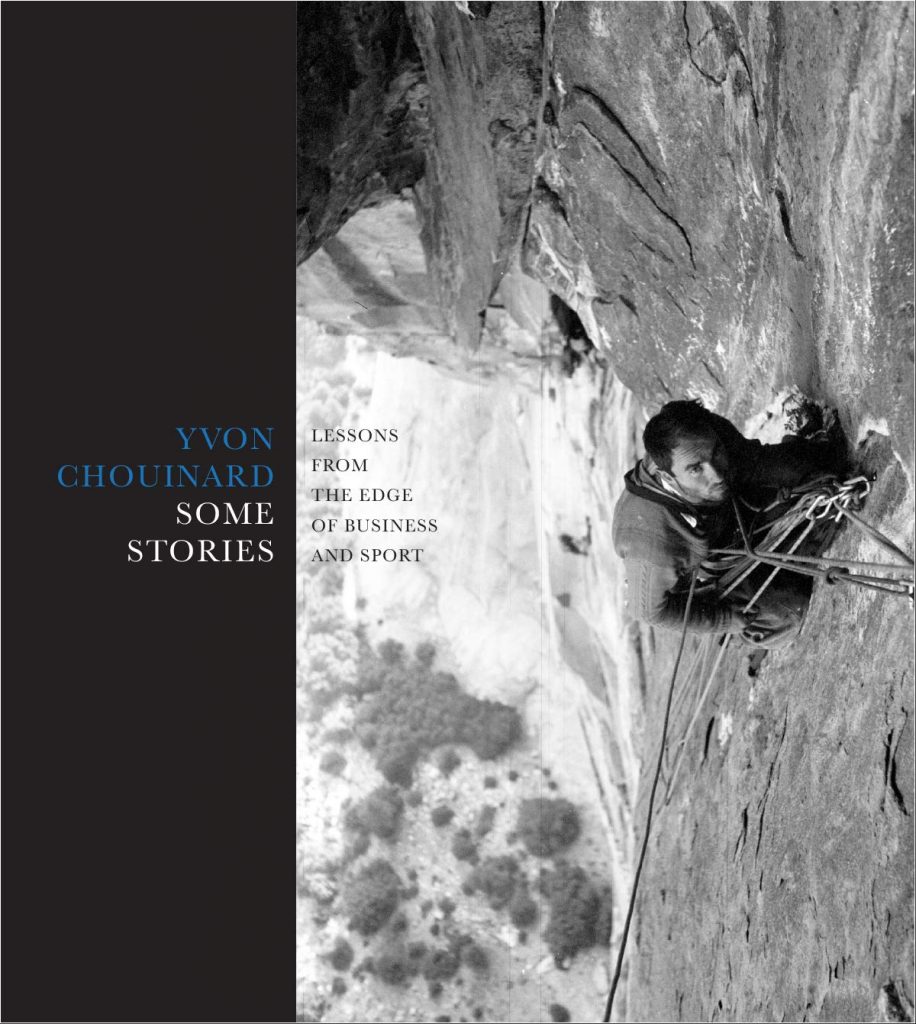

Some Stories: Lessons From the Edge of Business and Sport is the latest book from Yvon Chouinard. Some Stories is full of recollections, essays, and letters, many previously published, all gathered together from across the span of Chouinard’s life in business and the outdoors. They range from high school exploits as a beginning climber, to his experiences on mountains around the world, to time spent fishing varied waters, to the philosophy behind his popular and successful company. Chouinard’s adventurous life and his love of nature have led him to an iconoclastic approach to business.

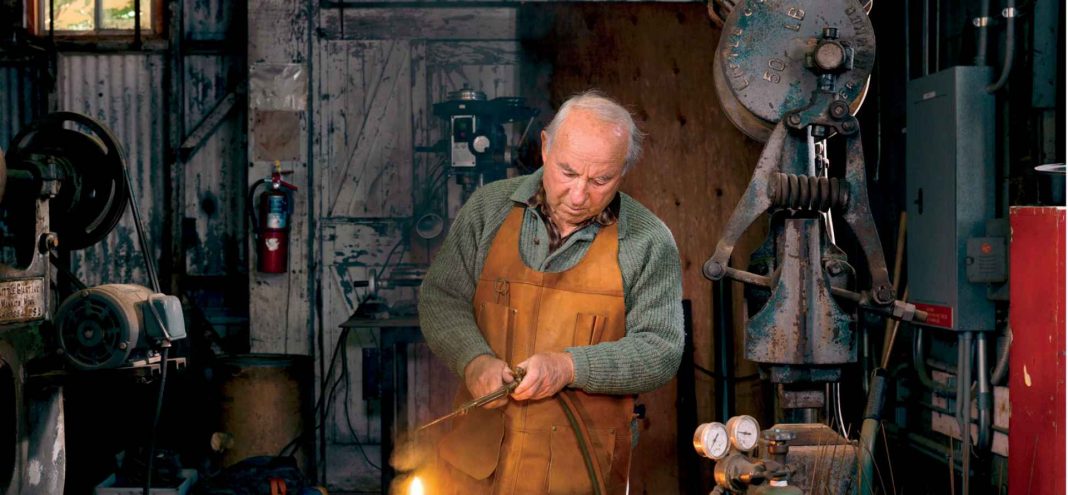

Chouinard no longer sleeps in abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps structures to save money, but he has retained the ethos for simple living and useful gear. Chouinard writes: “I enjoy manual labor and love using good tools that leverage the efficiency of my efforts. But not a tool or machine that takes away the pleasure of the labor. (I think of that banana cutter, which replaces a good tool: my knife.) I think the simple life really begins with owning less stuff.” That philosophy has also impacted Patagonia. Though they continue to make new products, Patagonia’s “Worn Wear” encourages people to buy used and teaches customers to repair their clothes.

Chouinard embraces life within limits. This can be seen most clearly in his passion for fly fishing. He is famous for using and advocating a simple tenkara rod, which he uses to teach others the joys of fishing. In recent years, he has converted to using fewer flies, sometimes only one for long stretches. In “Lessons from a Simple Fly,” first published in Trout and Salmon, he writes: “Limiting options forces creativity. Fishing for a year with only the PT has given me deep knowledge about what to do with that simple brown fly and a deeper understanding of fish. It has taught me that choosing a simpler life doesn’t mean choosing an impoverished life. Rather, simplicity can lead to a more satisfying way of fishing and a more responsible way of living.”

Chouinard came to outdoor gear through years of outdoor adventure. Living a life “close to nature” taught Chouinard “to try and protect what I love by leading an examined life, bearing witness to the evils and injustices of the world, and acting with whatever resources I have to fight those evils. This is something everyone needs to do in his or her own way.” For Patagonia, that has meant taking seriously such “considerations as quality, sustainability, environmental and human health, and successful communities.” Though every company is imperfect, Patagonia takes seriously priorities other than profit when making decisions and wants to create “products that enhance both human and environmental conditions.”

Chouinard’s philosophy may remind some Front Porch Republic readers of Wendell Berry. Though their approaches to life are not identical, there is considerable overlap between their worldviews. This kinship can especially be seen in Berry’s book Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community. For example, Berry and Chouinard have a shared perspective on technology. In Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community, Berry complains that “we live in a time when technologies and ideas (often the same thing) are adopted in response not to need but to advertising, salesmanship, and fashion.” In Some Stories, Chouinard writes that “although a designer and innovator, I have always believed that rejecting a possible technology is the first step in allowing human values to govern the pursuit of progress—just because we can doesn’t mean we should.”

Both Berry and Chouinard advocate for an economics that can harmonize with the natural environment and human needs. Chouinard asks: “Can we even imagine what an economy would look like that wouldn’t destroy the home planet? A responsible economy?” In particular, both men take issue with unlimited economic growth and consumption. Wendell Berry described Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community as “a book about sales resistance.” He writes that “unlimited economic growth implies unlimited consumption, which in turn implies unlimited pride, covetousness, lust, anger, gluttony, envy, and sloth…” Patagonia is known for consciously limiting its own growth. And in a unique ad campaign, Patagonia famously asked customers not to buy a jacket. For Berry and Chouinard, an economy that provides for human flourishing and environmental sustainability will include moderated appetites.

We might ask ourselves how two very different men came to similar outlooks. First and foremost, Berry and Chouinard have both spent a lifetime touching land and sea. In “Conservation and Local Economy,” Berry writes that people need “a mutuality of belonging: they must feel that the land belongs to them, that they belong to it, and that this belonging is a settled and unthreatened fact.” In “Seaweed Salad,” originally published in The Surfers Journal, Chouinard writes that “a lifetime of surfing, climbing, fly fishing, and running rivers” has given him “a sense of place. After experiencing a hundred bivouacs on mountainsides all over the world and trying to experience a river’s flow the way a fish would, I feel a certain sense of comfort in these environments. So does the waterman feel at home at the littoral edge who works with the ebb and flow of the tides, swell directions, interval and seasonal changes in fish habitat, and . . . pollution.” The responsibility and belonging that Chouinard and Berry feel to place is the product of prolonged exposure, deep mutual engagement, and dependence.

Chouinard is fond of a quote by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “Freedom is the acceptance of responsibility.” Now in their eighties, these men were not afraid to take the risk of assuming responsibility for their own paths when they were young. Chouinard has not only defied death in some of his adventures, he has defied conventional business wisdom. In his return to Kentucky and his embrace of his regional identity, Berry defied the conventional path to success for a writer. Each man embraced a lifestyle that aligned with his beliefs though it was out of step with society, and the result of those risks are the legacies they leave behind today. In a letter to his daughter, Chouinard writes that “I really believe the fish makes the person. Just like the mountains one chooses to climb influences your personality.” It was not just by sitting and thinking that these men developed their passions and philosophies. We must choose practices and places not just to defend, but to be shaped by.

Does it matter if there is some level of kinship between the philosophies of Wendell Berry and Yvon Chouinard? Many readers of Front Porch Republic regularly consider the application of Berry’s ideas. But for much of the world, Berry has long been seen as a John-the-Baptist type figure—a lone prophet in the wilderness, whose message we should heed, but whose lifestyle we won’t adopt. Jedediah Britton-Purdy’s recent article about Berry in The Nation was subtitled “Wendell Berry’s lifelong dissent.” And though Vox suggests “Wendell Berry is still ahead of us” when it comes to right livelihood, they agree his views on technology have led many to see him as a “curmudgeon.” Yvon Chouinard also shuns a computer on his desk. But the world sees him differently. He is “Patagonia’s philosopher king” according to the New Yorker. He may be unconventional, but he built a billion-dollar empire. That alone makes his lifestyle seem aspirational rather than out of reach. Being wealthy doesn’t make Chouinard a better representative of the values that he shares with Berry, but recognizing that Berry is not alone and that these values can be brought into the wider world, if imperfectly, makes their embrace of limits and simplicity more compelling and their approach to life seem more possible for others. Reading Some Stories is a good reminder that there are many stories of human flourishing that do not align with economics as usual.

While I appreciate the article and you bringing to light what seems a truly interesting man, I can’t quite see the Berry comparison. Particularly the claim he makes of gaining a “sense of place” gained from jetting around the world and being at home nowhere, apparently. But maybe I’m missing the connection?

Hi Brian,

Well, I agree that there is a pretty big contrast. But if you read Chouinard, it’s not from jet-setting, but from the amounts of time he’s spent in specific places. For example, there are certain climbs he’s done many times over many years and he’s seen how the face of a cliff has changed or how it’s been damaged by climbers, etc. Or specific places he’s fished for decades and seeing how they’ve changed. Or parts of the country he’s known before and after dams, etc. It’s still different from Berry, but I don’t know that I fully conveyed what it is, either.

Elizabeth,

Fair enough. There is certainly wisdom in his approach. And one would imagine that the world would be a much better place if more business leaders embraced some of what he does.

Thanks for the reply,

Comments are closed.