A quick update for subscribers to Local Culture: the printing was delayed a bit by COVID-19-related causes. However, our printer was deemed “essential,” (I’m sure because of their efforts in printing and mailing this issue) and your copies of the journal were delivered to the USPS on April 2nd. No one seems to know why they have now disappeared into the abyss, but we continue to hope that they will surface soon and arrive in your mailboxes. Thanks for your patience, and I trust you’ll find this issue particularly relevant as current events remind us of the need to decentralize our economy.

“Thanks to Bookshop, There Is No Reason to Buy Books on Amazon Anymore.” Alex Lauer describes how Bookshop.org is helping independent booksellers band together and compete in the online marketplace. FPR has refused to set up an affiliate account at Amazon dot hell (as the Bar Jester aptly names it), but we’ve set up an account with Bookshop. Feel free to browse some books written by FPR authors, and future book reviews will link to Bookshop. If you buy through those links, we’ll earn a 10% commission—that means you can buy books and support FPR and support an independent bookstore.

“Why We Should Love the Post Office.” Addison Del Mastro reminds us that the USPS remains a vital, democratic institution that needs to be sustained.

“The Mathematician and the Mystic.” David Guaspari reviews The Weil Conjectures by Karen Olsson. Simone and André were both complex, conflicted people, but their relentless pursuit of truth offers us a bracing model.

“Not Like the Flu, Not Like Car Crashes, Not Like….” Over at the New Atlantis, Ari Schulman, Brendan Foht, and Samuel Matlack have put together graphs that put COVID-19 in the context of other causes of death. These are helpful, I think, but the current obsession with graphs and statistics is also dangerous. On the one hand this is because all such charts are built on flawed data, but even more insidiously, they provide an illusion of panopticon knowledge and control. For why this is dangerous, see Cayley’s essay below.

“Questions About the Current Pandemic From the Point of View of Ivan Illich.” David Cayley, Illich’s thoughtful interlocutor in the excellent The Rivers North of the Future: The Testament of Ivan Illich as Told to David Cayley, draws on Illich in thinking about our response to the coronavirus. This is a long essay, but it’s worth pondering, and it’s the best case against a near-total shutdown that I’ve read. Even if you disagree with his conclusions, Illich’s framing of technological change as involving “two watersheds” is quite helpful as we consider which responses to the virus are appropriate and which go too far. FPR readers will certainly appreciate Illich’s defense of limits and right scale:

The events of recent weeks reveal how totally we live inside systems, how much we have become populations rather than associated citizens, how much we are governed by the need to continually outsmart the future we ourselves have prepared. When Illich wrote books like Tools for Conviviality and Medical Nemesis, he still hoped that life within limits was possible. He tried to identify the thresholds at which technology must be restrained in order to keep the world at the local, sensible, conversable scale on which human beings could remain the political animals that Aristotle thought we were meant to be. Many others saw the same vision, and many have tried over the last fifty years to keep it alive. But there is no doubt that the world Illich warned of has come to pass. It is a world which lives primarily in disembodied states and hypothetical spaces, a world of permanent emergency in which the next crisis is always right around the corner, a world in which the ceaseless babble of communication has stretched language past its breaking point, a world in which overstretched science has become indistinguishable from superstition. How then can Illich’s ideas possibly gain any purchase in a world that seems to have moved out of reach of his concepts of scale, balance, and personal meaning? Shouldn’t one just accept that the degree of social control that has recently been exerted is proportionate and necessary in the global immune system of which we are, in Haraway’s expression, “biotic components?”

“From the Cholera Riots to the Coronavirus Revolts.” Jesse Walker examines various nineteenth-century riots that broke out in protest of anti-cholera regulations that the working class perceived as too stringent. These hold lessons for authorities today who are trying to impose stay-at-home orders on a population that will grow increasingly restless. (Recommended by Bill Kauffman.)

“My Isolation Breaking Point.” Matt Labash’s story of an outlaw fly-fishing trip—catch-and-release fishing is apparently now banned in Maryland—is a trivial but telling example of Walker’s point: stay-at-home orders can’t be enforced; they are effective only when they have broad public support. Leaders who want them to be successful need to make a commonsense case for why they are necessary and when they can be eased (it would also help if they avoid blatant favoritism).

“What Do the Humanities Do in a Crisis?” Agnes Callard writes a remarkable defense of the fragile yet precious goods of humanist learning and contemplation. This essay reads like a secular version of C.S. Lewis’s “Learning in War-Time,” and even without the theological grounding Lewis relies on, Callard articulates much of importance.

“When Dvořák Went to Iowa to Meet God.” In a beautifully written essay, Nathan Beacom narrates Dvořák’s trip to the American heartland and the influence it had on his music:

His music, especially the music he made in America, dealt with the joy of home, but equally with the universal human feelings of loneliness, estrangement, and longing for a place to fit in. These feelings came especially alive during his summer in the Midwest, and through his journey to Iowa that year, we can learn something about the nature of that fundamental longing and about music’s power to console it. Ultimately, for Dvořák, music was a way of knitting our souls back together with the world and the God who first composed it.

“Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic.” David Yaffe-Bellany and Michael Corkery report for the New York Times on the inability of large farms and processing plants to adapt quickly to changes in eating habits and disruption to the supply chain. The result is sickening amounts of waste. During this pandemic, a food system built around “efficiency” turns out to result in both waste and want.

“Suspending WHO Funding Should Be Just the Beginning.” Lyman Stone argues that WHO needs to be drastically restructured: “It is not a crisis-response organization. In a moment of crisis, . . . the WHO will send a team of suits to stay in a nice hotel and act as government consultants, and then show up with a new vaccine a year after the epidemic is over.”

“Bill Kauffman reads Wendell Berry.” Bill Kauffman, the Sage of Batavia, reads Wendell Berry’s “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front” from his home studio.

“The Pandemic Is Not a Natural Disaster.” Kate Brown reflects on the ecological lessons we’re being reminded of: “In the midst of the coronavirus outbreak, this idea of a body as an assembly of species—a community—seems newly relevant and unsettling. How are we supposed to protect ourselves, if we are so porous?”

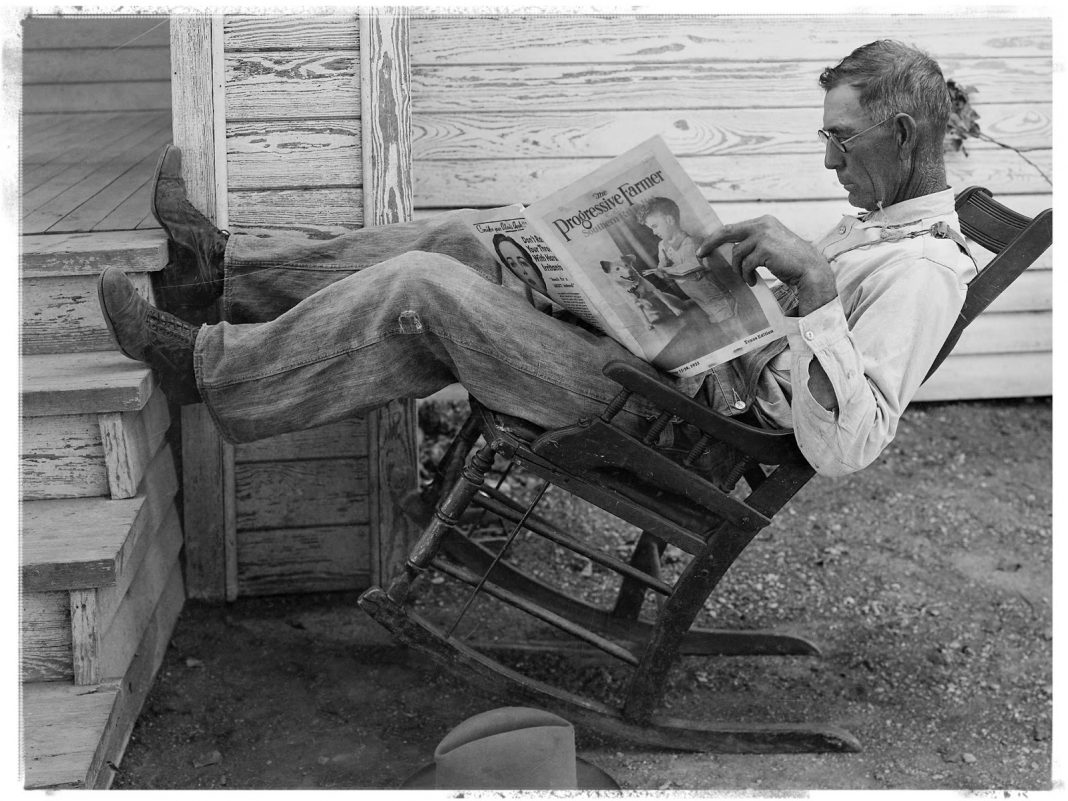

“Redesign Required: Principles for Reimagining Federal Rural Policy in the COVID-19 Era.” Katharine Ferguson, Anthony F. Pipa, and Natalie Geismar outline a set of principles that should guide government investments in rural communities: “Any full recovery for the U.S. requires building back better in rural and tribal areas. Crafting policy that aligns with modern rural realities requires overcoming stereotypes, understanding the interdependency of rural and urban areas in creating resilient regions, and a recognition of the diversity of rural America.” (Recommended by Jason Peters.)

”Online Learning Should Return to a Supporting Role.” David Deming argues online learning can’t replace the really important aspects of education.

“What the Sunrise Will Show.” Brian Miller writes about farming in the aftermath of storms, and in the midst of a pandemic.