Abilene, TX. Dorothy Day has, to this Baptist, been a kind of warm companion for numerous years now. For as a Baptist, the separation of church and state is a sacrosanct commitment which puts us at odds with many of the Reformation traditions, but one which I see in play in Day’s work. The separation of church and state for Baptists is not a commitment to the state’s absolute secularity, but first a plea for government noninterference: let the chips fall as they may, but just leave us free to confess the Lord without being coerced to do so. And as a Baptist, I think I know what this plea for liberty means, until I encounter the depths of this commitment for Day: anarchy.

Dorothy marries into the Baptist story in many ways, for she too remained famously skeptical of any and all government interference, refusing to cooperate with air raid drills or pay taxes. But for Baptists, the limits of separation generally stop at the church house door, while for Dorothy, her separation is more aptly named what she called it: anarchy. Influenced by the work of Russian thinker Peter Kropotkin, Day’s vision was far more than simply distance from government. It was a disavowal of the heart of secular governance which called for a new world to come up from its decay.

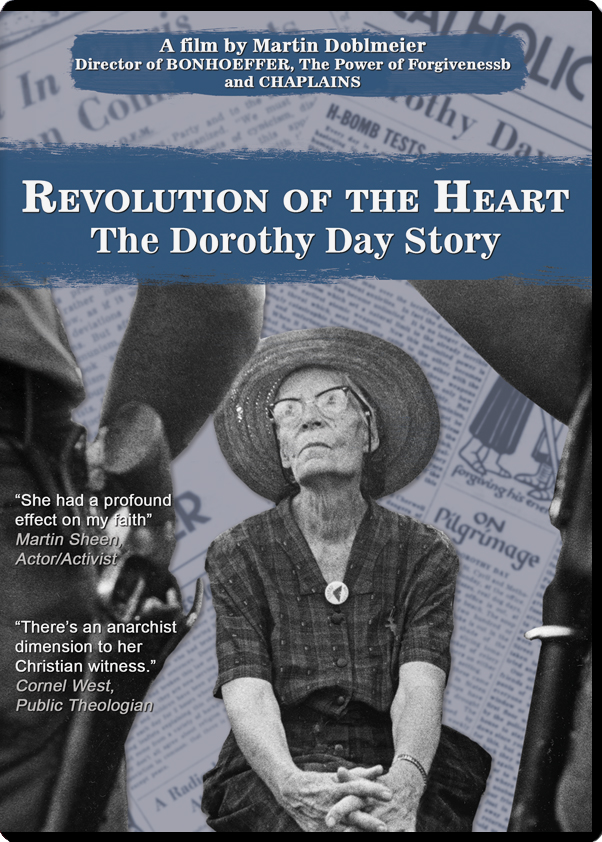

In Journey Films’ documentary, Dorothy Day: Revolution of the Heart, Day is reintroduced to a new audience, emphasizing Day not as a patron saint of the poor or primarily as a woman of deep Benedictine piety, but as a Christian anarchist. For Day, “anarchy” was a loaded term, for in her earlier days among the Communists, anarchy was paired with images of revolutionaries preparing to burn down the establishment. But for Day, as a Christian, “anarchy” was not only a way of standing against the coercive nature of the state, but for a very different kind of social ordering.

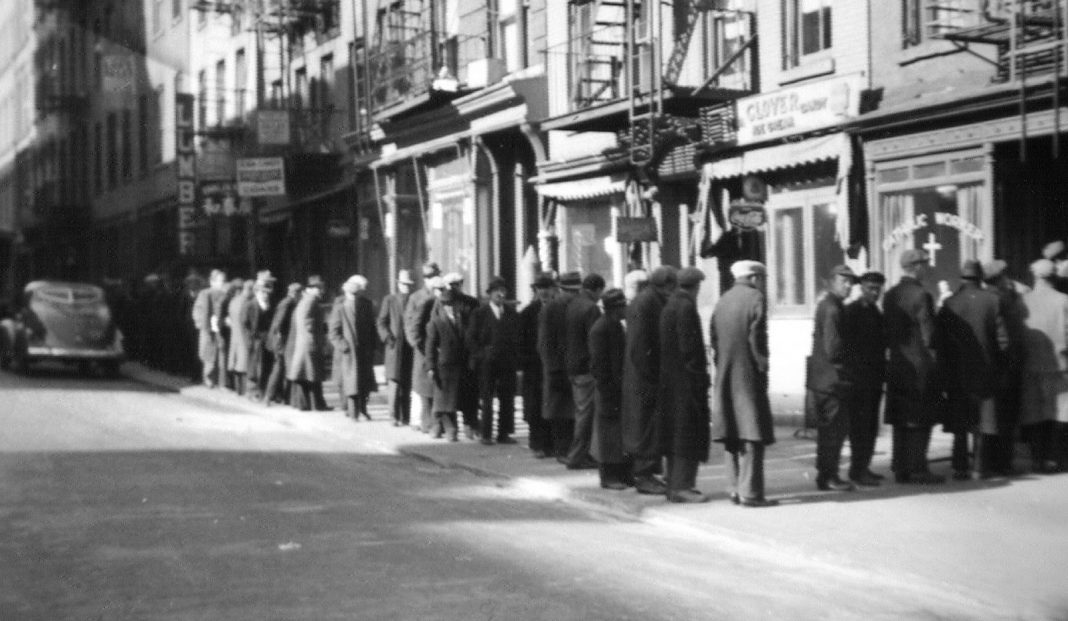

The stories about Day, the socialist turned Catholic anarchist, are well-known at this point. Her refusal to pay federal taxes and being threatened with seizure of the House is Catholic Worker canon, embodying the refusal of government involvement in the work of charity. Her oft-quoted dictum of “creating a new society within the shell of the old” embodied this philosophy, as she and Peter Maurin relied not on public funds to do their work, but on a network of donors and people of goodwill which stretched across the country. But Day’s relationship with public aid was a complicated one, for while she refused to pay federal taxes—as a sign of her refusal to participate in America’s increasing militarization—she also wrote favorably about various New Deal era issues, such as the Industrial Recovery Bill, and about the accomplishments of the public works programs under FDR.

So, if one could be an anarchist, while yet speaking affirmatively about government assistance, what does being a Christian anarchist really mean? For Day, anarchy was not the renunciation of all governance or government, but—to paraphrase Augustine—to make use of the goods of a common life toward a very different end, toward the creation of a new kind of world. To be an anarchist for Day was not about renouncing all ordering, but to renounce an ordering which did not attend to the person above all. To be an anarchist was not to shake your finger at government assistance, but to remember that institutions—whether of Church or state—did not displace the ongoing debt of love which was owed by all to all. If and when Day was charged with disorderliness by the state, it was not because she was openly calling for the withering away of the state, but because she was denying its power to order the way we care.

It is here that I need to introduce us to Cole Chandler. Since 2016, Cole and his family have been deeply involved hosts of the Catholic Worker community in Denver. After the previous home, which had stood for 38 years, burned to the ground, Cole helped to spearhead the building of a new home. But with the new house, a new challenge had arisen: permitting. In the 38 years of the previous house’s existence, no permit had ever been issued for the multi-family arrangement common to many Houses of Hospitality. But in the process of rebuilding, new questions were being asked by the city about this peculiar living arrangement. Though co-habitation was common in the city, beginning in 2018, the Catholic Worker house began to be singled out for further review. The House continued its local focus—providing long-term housing for migrants, refugees, and the homeless—but in 2018, the anarchist nature of the Catholic Worker houses was running up against the banal threat of bureaucracy.

Cole’s day job, with Denver Homeless Out Loud, a homeless advocacy organization, had already brought him into this world of permits and regulation, of city councils and leveraging public monies toward the common good. But this, he noted, was becoming a live question among the Catholic Workers. The resources of a place like Denver were sizable, and the access to these state and city funds for the good of the work raises important questions, particularly for those living in the shadow of someone like Dorothy Day.

As Cole described the struggle which had emerged in being able to do the basic function of the Worker House—provide hospitality—the struggle between the City of Denver and the Catholic Worker became apparent. For in city code, housing is to be used for single-family dwellings, in part to ensure safety, but in part to make sure that taxes are being paid properly. This net now catches slumlords and Catholic Workers alike in its net.

Since Day’s death, the Catholic Worker houses have grown nearly ten-fold in number, and with them, the question of what it means to relate to the state has grown more complicated. For with every provision of expanded health care comes additional requirements for reporting; with every provision of expanded policing and security comes increased restrictions on who Christians can assist. For Cole, the real promise of government assistance with new housing initiatives comes with new strings and new questions to raise, not the least of which is “What would Dorothy say?”

So what would Dorothy say? Day’s kind of anarchy sits now uneasily between prevailing political options. For Day’s anarchy rejects both a libertarian model of the state which would abandon the people to market forces as well as the big government which would provide for and yet restrict people. The ongoing questions of how to navigate the real practicalities of building codes, and of whether to use public money to further the spiritual good, remains live. But until then, Cole says, “we do potluck, liturgy, and works of mercy,” for these are the things which truly build the new world in the ashes of the old.

But as the new documentary reveals, in addition to refusing to be cowed by the state, Day’s anarchy involved a different and deeper kind of anarchy: a refusal to be saved by the state. The anarchy which led Day to refuse to accept the federal government’s assistance for her work was the same anarchy which also led her to refuse its protections. Journey Film’s documentary captures these stories as well, stories of Workers having to break up fights in food lines or turn out people who were endangering others, and all without recourse to the police. To be an anarchist for Day was not only a refusal to have their love limited by the word of the state, but to be open fully to the provision of God: it was to believe that God alone can save us and sustain us.

Such a commitment is described by Day in two different kinds of pairings of freedom and danger, a pair as intertwined as the ebb and tide of the Hudson River. The first kind is seen in The Long Loneliness, Day’s second account of her conversion, in which she tells us of her own conversion to the poor, and how she came to throw her lot among the destitute of the Bowery. In this story, we see the duality of freedom and danger that is Christian anarchy; it is not the descent of someone of privilege into a life of poverty, but the freedom and danger which comes with embracing the Gospel: you relinquish a great deal of choice over how your discipleship will be lived. Rather than raising her daughter Tamar elsewhere, she raised her in the midst of the Catholic Worker; rather than simply giving money to the causes championed by Peter Maurin, she gave herself. These kinds of stories, I think, are given not to champion her own virtue, but to display what God’s grace has done in her own life, joining her to the broken Christ who suffers with humanity, and the danger of saying yes to that call.

By entering into communion with the suffering of the world, Day highlights that the first movement of Christian anarchy is one of departure, not in resentment of the world left behind, but in pursuit of what is ahead. By the time she writes The Long Loneliness, Day writes with no hard feelings toward capitalists or businessmen, no animus toward presidents. As a younger woman, she threw in her lot with those who sought a new class war, and in some ways, she never leaves that sentiment, decrying wealth as Mammon and capitalism as theft. But she bears no ill will toward capitalists, pitying them as those caught in the throes of a system which is killing them. The danger and freedom of anarchy was one which liberated the soul from the tyranny of a perceived gift (capitalism) which was only ever a poison.

Christian anarchy, in the first movement, then, is for Day not a refusal of the goods of creation, be they in the form of human society, the exchange of goods, or the building up of the common life. Rather, it is a call to leave the old and corrupted forms of these things that we might see how they can be redeemed.

The second kind of story regarding freedom and danger roots Christian anarchy in the mundane: stories of ministry and violence in the Catholic Worker. At one point in the documentary, actor Martin Sheen tells his own story of serving in the soup kitchen line when a fight broke out; in her journals, Day tells of having to remove drunk patrons or having to negotiate the difficulties of communal life when someone became belligerent or dangerous. With anarchy, particularly in the personalist form championed by Day, there comes a refusal of not only the organization and provision of the state, but also the safety of the state. In Day’s stories, there is a decided absence of the police as a mediating presence; the only interactions with police which are present in her own writings are when she is arrested or imprisoned.

If Christian anarchy is first, then, a call to seek and find the beauty of God’s work and to leave behind the safety of Egypt, it is secondly a sober reminder that in Egypt, there is a simulacrum of safe order which the desert of the poor cannot promise. To embrace the kind of anarchy which Day described was not only to refuse the organization of the state with respect to taxes, but to refuse its safe ordering of the world as well. To be an anarchist, at the root, is to trust that the God who opposes the false order of the state is the same God who sustains the follower in the absence of that state’s provision.

The Christian anarchist is one, for Day, who seeks the common good which the state cannot begin to know how to preserve. For the state preserves the common good by law and impersonal decision; the Christian anarchist works by suffering the absence of the state’s safety and embracing the task of rebuilding the world without its promises. It is the willingness of Day to write newsletters, to attend meetings, and to meet with officials, but not to receive their help unless it was a free gift which could be used regardless of the purposes of the giver. The Catholic Worker took up public space in the world, never paid taxes on its building, and took that gift from the world as an opportunity to restore to health the very ones left behind by the state’s best intentions.

As the American 2020 election draws closer, the oddity of Dorothy Day’s anarchy comes squarely into view. For some time, her opposition to the nationalism and militarism defended by conservative political voices has been a natural connection to make. But based on her own writings, it is hard to see that Day could be anything other than a strident opponent of many of the popular planks of the Democratic party: Medicare for All, universal basic income, access to abortion, and higher federal taxes among them.

This is not to say that Day is opposed to medical access or a believer in the free market, but for Day, the intimate attention and care which one person gives to another—an attention we all deserve–cannot be accomplished by the state, full stop. It is an anarchy which rejects both the expansion of the state’s care and its militarism, both its safety and its oppression. It is a dangerous kind of anarchy, for it is one which puts itself unreservedly in the care of God, beyond any promises or provisions of any kind of state.

As the Catholic Worker continues to expand across the country in the forty years after Day’s death, their anarchism is not a nihilism which rejects any and all order or communion. It is one which seeks the common good by tending to the rejected parts of even the best state, and by refusing the state’s safety net which comes with many other strings. It is the way of the little order, the little love, the local care, and the intimate attention which grows the common good from the inside out and the bottom up–all the way up to God.

Let us close with the question which Cole posed, and with which Christian anarchy continues to haunt us: “What would Dorothy do?” Dorothy provides the political realist with no recourse, seeing the mechanisms of governance as laden with temptations and vices. She likewise gives no quarter to the separatist who would imagine that the way forward is one of distance from the world. It is doubtful whether she would have really cared, then, if both of them simply left her alone to continue doing the small work of building a new society within the shell of the old, enacting the works of mercy, praying for her enemies, and slowly cultivating a new heaven for everyone who wants to be a part of it in the middle of the old, heavy, burdened earth.

I’ve tried to admire Day, but I just can’t seem to do it. Probably says more about me than anything, I suppose, but the life-as-activist model has always rubbed me the wrong way. This article here: https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2014/12/free-telescopic-morality-machine/ is one of the best articles FPR has ever published, I think, and I guess I find the approach to relating to the rest of the world taken in Gurri’s article a lot more appealing.

We don’t all have to have the same vocation/calling though, so maybe I’m just being uneccessarily grouchy about other people’s vocations.

Your excellent piece makes we want to see the new documentary all the more. It also suggests that while Dorothy supported some New Deal programs, somehow she would not be favorable to, say, Medicare for All or UBI. In the current calamity, I wonder whether her sense of subsidiarity (i.e., not just localism but a sense of the appropriate scale of things, whether higher or lower) wouldn’t lead her to embrace measures which can only be undertaken at the federal level, given the extent of the ongoing collapse. Would she mount a kind of Illichian refusal of institutional healthcare aimed at addressing the COVID virus? Or would she argue that the Catholic Worker charism–like religious life–is best understood as a prophetic calling not shared by everyone?

This is a wonderful essay, Myles, filled with challenging and suggestive ideas, and a wonderful companion to your essay on Day and Peter Maurin last year. I particularly like–pace Aaron’s comment above–how you elaborate on the real sense of danger (and maybe even the temptation to understand oneself as a heroic risk-taker) which will unavoidably attend any genuine dedication to an order which operates without the promise/threat of coercion. I think about what it would mean were I to put myself in such a situation, dealing with drunkenness and belligerence and possibly violence, without the law to fall back on, and I think about my children and the domestic virtues which are in many (not all, certainly, but many) ways inextricable from embracing the systems of the state, and I decide: no, thank you. But there is some regret which comes with saying that, and such regret is probably appropriate. It is a matter of recognizing holiness, a better way of life, and being blessed by that recognition, but also accepting that it’s not for me.

Incidentally, I wouldn’t be so quick to assume that Day couldn’t support Medicare for All or a universal basic income. Elias’s observation above about how subsidiarity comes into play is on point, I think. And as your own essay notes, she was a strong supporter of recovery efforts that which people to work, thus providing them with a degree of economic security–and thus freedom–which bankruptcies, foreclosures, and bank failures had taken away. I’m not the scholar of Day’s work that you are, but I try to keep in mind an observation made by Adolph Fischer (of Haymarket Riot infamy): “every anarchist is a socialist, but every socialist is not necessarily an anarchist.” Day’s approach, which imagines a socially empowering governance of people in living in equality and community, is a good standard for interpreting and applying that observation, I think.

The word is “descent”, not “decent”.

Thanks!

While Day frequently used the phrase “building the new society within the shell of the old, it precedes her, going back to the Industrial Workers of the World.

Comments are closed.