Evans, GA. I have not read much poetry in my life. What I have read leads me to think there cannot be any other genre of literature so fundamentally opposed to the basic nature of modern letters.

Such was my impression as I read The Slumbering Host, a volume of poems that were previously published at The North American Anglican. Contemporary prose—both non-fiction and literary—must be clear and accessible or readers will not spare it a second thought. I myself admire clarity in others’ writing and strive for it in my own.

In marked contrast to our literary zeitgeist, the poems in this volume are not meant to be processed at a glance and then left aside. Indeed, I found it necessary to re-read almost every poem multiple times just to grasp its basic sense, and even now I would not claim to fully understand them. Yet it seemed to me that part of their value lay precisely in the fact that I could not comprehend them in an instant and move on. In this respect the editors have met their goal of gathering “poems that ask to be read, and read again” (1).

But depth and complexity are typical features of poetry as such—I have not yet said anything about the character of this particular volume and why it is worth your time.

I do not wish to narrate what any of the poems are about in detail. Certainly I could summarize and boil them down to their basic subject matter, but I fear that to do so would unavoidably diminish them. One of the editors puts it best when he says these poems “seriously engage with the world in which we live. Not the world as we might prefer it, and not the world which we fear it to be” (1).

That world we live in is one of weakness, loss, and unfulfilled dreams, but also one where every moment is significant and “charged with the grandeur of God.” Such moments ordinarily go by so fast we fail to appreciate many of them. The poetry in this book captures some of those everyday moments and holds them up in a light that makes possible another kind of clarity, not that of simply worded declarations on a page, but that which concerns our own selves and souls. I saw myself in many of these poems, and I trust you will too, simply by virtue of being human. Here again the poets and editors have succeeded in their task “to make beautiful things. If they’re beautiful, the truth will follow, and if true, then good in turn” (1).

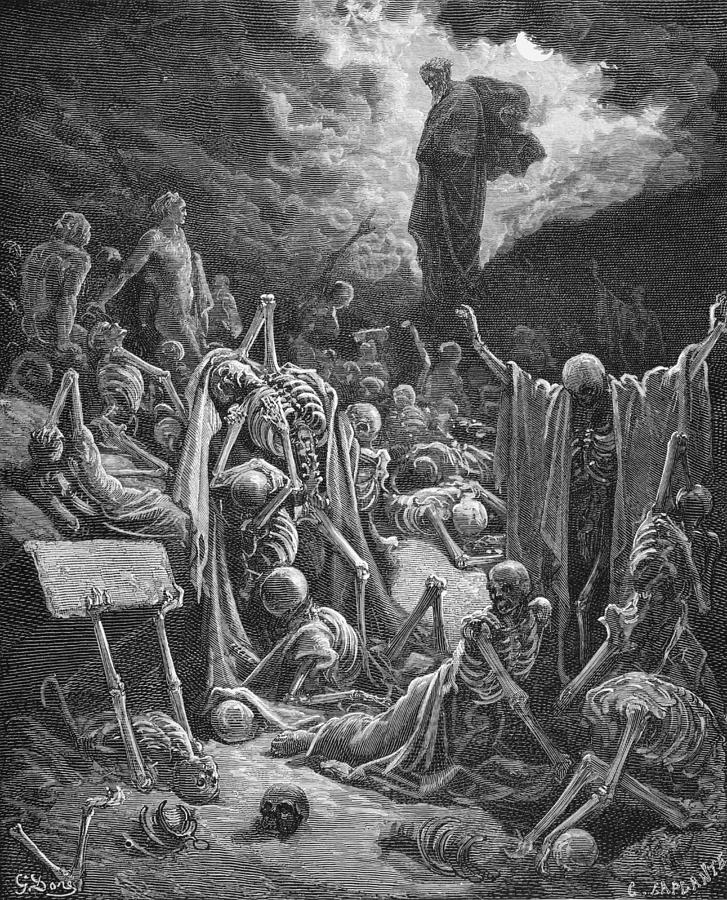

This review’s brevity (especially compared with my usual output) might be taken as a sign that I did not really enjoy the book. May the reader banish the thought from his mind. Rather, I end here because I can add no more without risking superfluity—for it is in the threefold experience of beauty, goodness, and truth that God’s Spirit can inspire us, the slumbering host, to live again and stand on our feet, “an exceeding great army” (Ez. 37:10).