Cleveland, OH. St. Thomas Aquinas is one of the most famous Christian intellectuals in the history of Christianity. He ranks alongside luminaries like St. Paul, St. Augustine, John Calvin, and Jonathan Edwards as among the most well-known men of the Christian tradition. While most know the angelic doctor as a central figure of scholasticism and the namesake for Thomism, the Thomistic Thomas—the technical Thomas of definitions—is, in my view, the wrong Thomas to be promoted for the ills of our age.

Thomas and the Enchanted Cosmos

Thomas had a deep cosmological, indeed, ecological, side to his theology that is often undervalued. Thomas’ cosmological theology was thoroughly enchanted and magical, and it is his enchanted and magical view of the cosmos that we so critically need today. While Thomas’ cosmos is teeming with life, anima, what is most important to understand is how everything is intimately interlinked with everything else. There is not a single space in Thomas’ cosmological vision that is not interconnected in a harmonic ladder stretching up to God.

Even matter, which does not possess a soul, is crucial for the formation of plant life and the vegetative soul: “Different kinds of things produce in different ways, those on a higher level producing in a more interior way. The lowest level of all is that of non-living bodies.” Matter may not be able to reproduce after itself, but its crucial function in helping foster life itself, through its attachment to plant life, is recognized by Thomas. Without it, we cannot have the more grand and beautiful forms of life that depend on it: “The living things closest to these are the plants, in which there is already some interior production, turning the inner juices of the plant into seed which, committed to the earth, grows into a plant . . . The first beginnings of production are also outside: for the inner juices of the tree are sucked up by the roots from the earth which nourishes the plant.”

Above plants, but connected to them, is animal life and the animal soul. The animal soul is “endowed with sense-awareness.” The animal soul possesses the five senses, but its power lies in motive power, and affective and aggressive emotion which “empower us to enjoy things delightful to the senses.” Animal life depends on plant life, which depends on matter, which are all interconnected in a grand ladder of being reaching up to the celestial heavens “to which the whole creation moves” as Tennyson poetically, and more recently, put it.

Connected to the animal soul, but still above it, is the rational soul: “The highest, most perfect level of life is that of the intellect, for intellect can reflect upon itself and understand itself . . . The human mind, even though it can come to self-awareness must still start by knowing outside things.” What is crucial to recognize from Thomas is how human self-knowledge is tied to the outside world, to the world of creation, to the world of animals, plants, and matter. Indeed, without the hierarchy of the ladder of being humans could never come to know themselves.

From this interconnected, cosmological perspective, we see just how far the rational soul of modernity has fallen. Deracinated and cut-off from the world, the human floats around in an atomistic vacuum with no relationships to anything as if a walled off piece of dead matter itself. (Which is what the modern materialist anthropology asserts: that man is nothing more than a mass of matter spun in motion.)

“Each soul,” Thomas reminds us, “has a primary goal—for the human soul what it understands to be good—which all its other goals serve.” Thomas further explains what the good is: The beauty and goodness of God to which all things, in their particular instantiations, try to embody to bring the cosmos and world we inhabit to fullness of life. “God’s providence,” Thomas writes, “orders everything to a goal—his own goodness; not as if what happens could expand that goodness in any way, but things are made to reflect and express it as much as possible.” Thomas’ cosmos is mystifying because it is a cosmos permeated with love, relationality, and attachment. Everything, ideally, moves together in a seamless waltz, an orchestra, an opera, of life and love which blossoms to produce a grand radiance reflecting the life, love, and beauty of the Trinity.

Thomas and the Return to Enchanted Roots

What Thomas’ cosmological theology and theological anthropology teaches us is that we live in a world of relationships that we must be attached to in order to more fully know ourselves. A life of deracination is not only unhealthy for the soul— for life—it is the surest thing to destroy the consciousness of sacramentality. Once this consciousness is destroyed, as per Thomas, we cannot understand ourselves, our place in the world, or the world itself. We live in a deracinated world because we have destroyed sacramentality, which is a form of (inter)connectedness.

It is not surprising that with the death of the soul has come the death of the world. Everything has been reduced to lifeless matter moving to its inevitable death. With such an attitude, there is no motivating force for attachment and preservation. There is no call to divinization. There is no call to participate in the mystery of life found in that interconnected waltz of the three levels of the soul processing and singing hymns of beauty and glory. Thomas’ world is one of plurality and vitality instead of the dry, sterile, and empty rainbow of the “new science.”

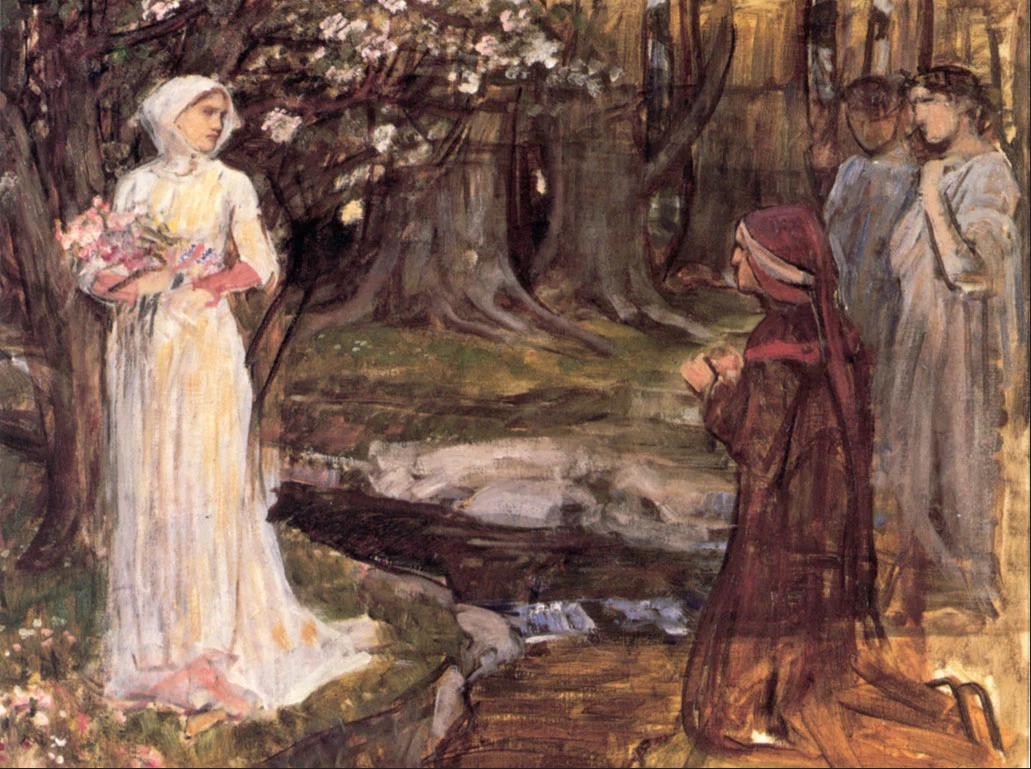

Thomas Aquinas is a most profound ally to the localist cause because Thomas understood the essentiality of a life of attachment and wonder. To marvel in the world we inhabit, to root our ability to marvel in the very soil that nourishes the plant and animal and rational souls, ensures the true deep ecology that gives life to the human person. Once this awe, this marvel, this wonder, is destroyed—which comes with the severing of life from that ladder of mystical being—we fall into the world of lust, objectification, and, ultimately, death. No wonder that the expulsion from Eden ends not in death but in the restoration, the replanting, into a New Eden resulting in life. As Dante said of this New Eden, while paying homage to Thomas, “From those holiest waters I returned / to her reborn, a tree renewed, in bloom / with newborn foliage, immaculate, / eager to rise, now ready for the stars.”

Thank you

Comments are closed.