Belmont, NC. In that most radical and reductive of tracts, the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx proclaims the revolutionary ethos of that harbinger of discontinuity—the bourgeois spirit:

The bourgeois, wherever it got the upper hand, put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations, pitilessly tore asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors,’ and left remaining no other bond between man and man than naked self-interest and callous cash payment . . . Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into the air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

Here the tradition-dismembering bourgeois spirit is a specter as world-shattering as its inverted socialist doppelgänger. Reductive as he was, Marx was not alone in reading the bourgeois spirit in this manner. The Catholic historian Christopher Dawson shared some of Marx’s concerns concern that in the bourgeois world the urbanized proletariat, toiling endlessly for the nouveau lords of capitalistic commerce, is cut off from the duties of distributive justice, which their aristocratic and feudal forbears either executed or at the very least praised with their lips. As Dawson explains, the bourgeois spirit “turns the peasant into a minder of machines and the yeoman into a shopkeeper, until ultimately rural life becomes impossible and the very face of nature is changed by the destruction of the countryside and the pollution of the earth and the air and the waters.” But Dawson’s displeasure with the bourgeois mind reaches beyond mere Marxist anxieties over the ascendancy of alienation, the gluttonous destruction of the earth, and the exploitation of many who inhabit it—substantive as these crises may sometimes be. For the Catholic historian, the highest spiritual matters are at stake: “there is a fundamental disharmony between bourgeois and Christian civilization and between the mind of the bourgeois and the mind of Christ.”

[Enter a litany of supplications to the parade of saints who play patrons to hopeless cases. St. Jude & Co., pray for us!] “We are all more or less bourgeois and our civilization is bourgeois from top to bottom,” Dawson contends. Our world does not merely mirror bourgeois prejudices and “virtues”: it aggressively advances them. Given the saturation level, there would seem to be no exit. Dawson continues, cautioning us away from “treating the bourgeois in the orthodox communist fashion as a gang of antisocial reptiles who can be exterminated summarily by the proletariat”; nonetheless, he insists, we must become more cognizant of both what the bourgeois mind exterminates and what it erects in its stead. There is no question that for the ordinary, bourgeois human being, life is more enjoyable and filled with more opportunities than their ancestors enjoyed: an entire culture of amusement everywhere awaits him. The bourgeois is “free to lead his own life, to mind his own business,” free to reap the material benefits of this mass civilization. To do so, though, he has to “put off his individuality and conform himself to standardized types of thought and conduct.” He who would escape the pressures of this position must, Dawson notes, “undergo a kind of penance.”

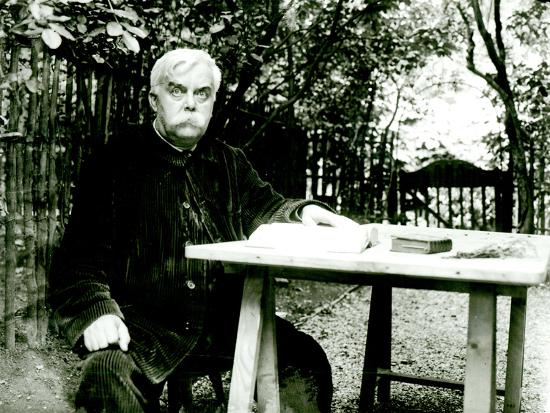

The Catholic writer Léon Bloy underwent this very penance. The Léonine Parisian and reactionary Catholic gave himself two nicknames that nicely capture his grandiosity and self-deprecating sincerity: “The Ungrateful Beggar,” a reference to his perpetual indebtedness and unremitting dependence on the donations of friends and perfect strangers for his family’s material sustenance, and “The Pilgrim of the Absolute,” an encapsulation of the totalizing hunger for God that pervades his prophetic life and works. Bloy’s most egregious excoriation of the bourgeois, the one that closes his case as an unrespectable offender and permanent penitent, appears in Exégèse des Lieux Communs, only a portion of which Raïssa Maritain translated into English under the ironical title “The Wisdom of the Bourgeois.” Of this volume Walter Benjamin wrote (in a letter to Gershom Scholem): “The splendid exegesis of the lieux communs by Léon Bloy; a more embittered critique, or better, satire, of the bourgeois than this could hardly have been written. By the way, in terms of the philosophy of language, it is a well-grounded commentary on the way they talk.” Bloy’s fellow-traveler Christopher Dawson is also keen to the trite sayings by which the bourgeois spirit strives to maintain “a respectable average standard. Its maxims are: ‘Honesty is the best policy,’ ‘Do as you would have done by,’ ‘The greatest happiness of the greatest number,’” among others. Even though such moral currency does not buy what it used to, countless among the bourgeois employ it to pay their way through life. As Bloy-translator Erik Butler would have it, in “The Wisdom of the Bourgeois” the Ungrateful Beggar treats “everyday sayings as coins that have passed between so many impure hands that they have lost the value they once held. The parties to blame for the Great Depression of Spirituality (as it were) belong to the hated bourgeois, the bugbear of reactionaries and revolutionaries alike.”

If the bourgeois’ metaphorical coins have suffered inflation, their literal monies are also made to suffer, but “redemptively”—through usury. Bloy explains: “‘It’s not like I’m putting a gun to anyone’s head,’ points out the affable loan shark charging fifty percent interest. ‘I’m the one taking the risk, and the money has to be put to work.’” Bloy reads the bourgeois mind as having a deviated spiritual depth. A precept such as “put your money to work” is, he says, “far more theological, at bottom, than economic.” In a manner that continues Max Weber’s assertion that the bourgeois world is invented and expanded not through material alterations so much as metamorphoses in the “spirit,” Dawson (citing Der Bourgeoisie, written by Weber’s friend Sombart) argues that “the bourgeois type corresponds to certain definite psychological predispositions. In other words there is such a thing as a bourgeois soul and it is in this rather than in economic circumstance that the whole development of the bourgeois culture finds its ultimate root.” What Bloy gives us in Exégèse des Lieux Communs is an “exegesis” of the sacred scriptures on which the bourgeois mind is fed and the bourgeois soul is bred. After chewing them thoroughly, instead of digesting them the wild ass of a man spits them out complete with little commentaries that serve as literal apocalypses (unveilings) of the conventional wisdom that guides the bourgeois and beckons all souls with its invisible hand.

In one of his first expositions, Bloy countenances the maxim “Nothing is absolute—there are no absolutes.” Bloy reveals the bourgeois, who is typically rendered as middling and small-minded, as a godlike creature, “armed with this thunderbolt [there are no absolutes].” When these “bibbers of a foul nectar” turn toward the “profitably Relative” with utter nonchalance, do they not know that “nothing is so bold as countermanding the unalterable, and that to do so implies the obligation of being oneself something like the Creator of a new earth and a new heavens?” Although it is typically the conservative who critiques the utopic ambitions of left-wing projects as hopelessly bent on making the eschaton immanent on this earth, Bloy’s second sight shows him that the “conservative” bourgeois also strives to create a new cosmos. As Bloy notes, the revolutionary character of “there are no absolutes,” seems unnoticed to the bourgeois, who defer to this saying when faced with inconvenient moral dilemmas. But, Bloy demonstrates, under the regime of “Nothing is absolute”:

At once we are entitled to wonder whether it is better to slit or not slit one’s father’s throat; better to possess twenty–five centimes or seventy-four million francs; better to be kicked in the ass or found a dynasty . . . in a word, all identities go by the board. It would be rash to maintain that a bedbug is wholly a bedbug, and must not aspire to having a coat of arms.

Yes, he concludes, this maxim makes “the duty of reshaping the world . . . imperative.” Here Bloy echoes Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s contention that the bourgeois world is both conditioned by relativism and is the conditions of its flourishing. When the “model of the free market imposes its implacable laws on every aspect of life,” Benedict XVI writes, “authentic Catholic ethics now appears to many like an alien body from times long past . . . Economic liberalism creates its exact counterpart, permissivism, in the moral plane.” Of course, in Bloy’s hands, the same exegesis assumes a comedic height; it crawls—like a slumlord’s top-floor tenement—with bedbugs.

Exégèse des Lieux Communs is filled wholly with vignettes satirizing such variegated pearls as: “A man does what he can”; “He who gives to the poor lends to God”; “Business is business”; “A penny saved is a penny earned”; “Every man for himself and the Good Lord for all”; and “Religion is so consoling.” Consider Bloy’s analysis of the latter: “It implies that you have just enough religion not to resemble those publicans who sorrowfully fast from one end of the year to the other, while you all the while polish off exquisite meals in great peace of conscience. You owe nothing to people who are dying of destitution, since they have religion to console them.” This same shrewd, self-interested surrogate of charity shows up in “Giving to Charity,” of which Bloy offers a “translation for the use of pious bourgeois”: “You have an income of three hundred thousand francs, you give a few pennies at the church door, then you dash off in an automobile to devote your attention to vile or silly doings. This is called charity.” According to this new “translation” of charity, caritas becomes opiate. “Religion then becomes a bazaar of reciprocal consolations, a genteel bazaar where are continually exchanged words of consolations.” The very continuousness of these exchanged succors seems to betray the degree to which the speaker must go to paper over that same religion’s stained glass of suffering.

In passages such as these, Bloy proffers, in guttural guise, a thesis that lurks in the work of such reputable scholars as Philip Rieff and Christian Smith: in the Time of the Bourgeois Mind, religion assumes a predominantly therapeutic character. What blind spots the bourgeois mind must cultivate, nice flexible ones that can block out even such blatant signs of contradiction as “the time of the Martyrs,” when much less was said about consolation, when “consolation was postponed until the coming of the Paraclete, a coming regarded as distant, and while awaiting this Third Reign of God on earth, men though they must suffer at the foot of the Cross, in the Blood of the Father of the poor.” The zealous saints who surrendered their lives in a manner fierce and absolute and bereft of sentimentality stands in startling contrast to those mediocre souls who prefer a “honeyed little sentence whispered in shadow” to “the Suffering and Ignominy” which remain perpetual “means of building a spiritual cathedral more magnificent and higher than all the famous basilicas.” How, he concludes, by what hellish twist can we be “consoled by the Bloody Sweat of the Son of God”? And once again, chewing the apothegm, Bloy spits it out unveiled: unwilling to accept the costs of Christianity’s distant hope, the bourgeois soul does religion as one does dope—does so, of course, in the comfort of his own home rather than in those seedy opium dens.

One can feel the camel hair of Bloy’s prophetic mantle more acutely still in his exposition of “A penny saved is a penny earned.” Assuming a parabolic posture, he reveals “He who sets a little money aside” as “a man who has a burial place built for himself in a dry spot safe from worms. A precaution against the poor tenants of damp houses, who are ever disposed to gnaw at the improvident.” This man is certain that in saving he sets for the poor an example infallibly more valuable than alms. Still more, the man must set the money so deep into an insured account, hidden from sight. Just in case he were to meet a poor wretch dying of hunger, he would then be protected against the possibility that, “the heart of man being frail, [he] might feel moved. Take care, this is the moment of trial, this is the hour of fearful temptation. Be generous and refuse with vigor. Remember, the shade of Benjamin Franklin is watching you.” And he is, dear reader, more so than Big Brother ever will.

The bite of Bloy’s irony is at times poisonous, and as such it occasions consideration of what David Foster Wallace said of irony in “E. Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction”: pervasive irony marks a “weary cynicism” which is essentially a mask to cover “gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté . . . What passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human is probably . . . to be in some basic interior way forever infantile.” Wallace notes, though, that, “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.” This, Wallace notes, “is because irony, entertaining as it is, serves an exclusively negative function.” On the other hand, irony of the sort Socrates used so liberally is not merely negative. As Romano Guardini said of Socratic irony, its “its object is not to expose, to wound, to despatch, but to help.” It aims to liberate, to serve truth. Guardini goes on: “Socrates’s concern is, above all things, for an inward mobility, a living relation to being and truth, which can only with difficulty be elicited by direct speech. So irony seeks to bring the centre of a man into a state of tension from which this mobility arises.”

Which species of irony escapes Bloy’s mouth? Tongue-in-cheek, speaking in a metaphorical key, Bloy himself “admits that it lies outside my power to remain calm. When I’m not killing, I must injure.” With his right hand, then, he at times commits that exclusively negative, cynical irony of which Wallace warns us. But with his left hand, which perhaps does not know what his right hand is doing, Bloy delivers satires that aim to liberate souls from cages they did not even know they occupied—an understandable ignorance, seeing as these same cages were well-furnished, with new countertops made from the same marble (but do please ignore this unpleasant detail) undertakers use to make gravestones. Beyond this, Bloy’s prose reaches past all species of irony entirely, and the projectile vomit of certain satirical lows cannot, even by its sickening stench, hide the fact that his bad breath is at time overpowered by the odor of sanctity.

Only a perfectly sincere pilgrim of the Absolute could, in conducting his exegesis of “Business is Business,” move from a mockery of American pragmatism ( “In Paris you have the Saint Chapelle and the Louvre, true enough, but we in Chicago kill eighty thousand hogs a day!”) to a mystic’s vision of the nothingness creaking the bed of the bourgeois night:

It would be impossible to say exactly what Business is. It is that mysterious divinity, something like an Isis of the swinish, by whom all other divinities are supplanted. It would not be rending the veil surrounding this mystery to mention, here or elsewhere . . . Business is Business, just as God is God, that is to say over and above everything. Business is the Inexplicable, Unprovable, the Uncircumscribed, the point where it is enough to utter this Stock phrase in order to solve all questions, in order to instantly muzzle reproof. When these seven syllables have been uttered, everything has been said, everything has been answered, and there is no hope for further Revelation.

“Business is Business,” “the umbilicus of all Stock Phrases, the age’s ultimate word,” speaks like Hermes on behalf of its god, surreptitiously stating that its god is beyond criticism. But in so doing, the bourgeois mind inadvertently admits that it has bestowed Business with a religious character. Ironically, this puts us in a position to employ Marx’s own argument to a different end. Marx asserts that “The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.” For our purposes, we must translate this fine line from the poeticized German, putting it in plain English: “The criticism of the bourgeois spirit is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that couch of comfort of which bourgeois spirit is the halo.” The couch, by the way, is crawling with bedbugs of Bloy’s own making. But if he sends you fleeing from your seat, terrified by the fact that what once comforted you is also consuming you, Bloy does not leave you no exit. He leaves you standing in disbelief over what just happened, but he sets your feet at the threshold of a cosmos yet populated with the Inexplicable, Unprovable, Uncircumscribed God.

Ironies shadow puppet the walls of history, dwarfing the earnest efforts of too many. As Dawson explains, the author of the Communist Manifesto was ghosted by the farcical specter that oppressed him: “Marx was himself a disgruntled bourgeois, and his doctrine of historic materialism is a hangover from a debauch of bourgeois economics and bourgeois philosophy.” Marx, Dawson continues, was in his concern for the proletariat moved not by love, but by hatred. He was “a man of narrow, jealous, unforgiving temperament, who hated and calumniated his own friends and allies. And consequently he sought the motive power for the transformation of society not in love but in hatred and failed to recognize that the social order cannot be renewed save by a new principle of spiritual order.” Bloy, too, was in a sense a “disgruntled bourgeois”; as the self-proclaimed Ungrateful Beggar explains in his autobiographical novel Le Désespéré, his father was “a shriveled little bourgeois employed in the Perigueux tax collector’s office.” In his capacity to alienate friends and benefactors, Bloy bears a striking resemblance to the portrait of Marx that Dawson sketches. And yet Bloy knew that only by a new—or, rather, ancient—principle of spiritual order, would the social order be renewed. Simone Weil’s question could have come from his mouth: “Our period has destroyed the interior hierarchy. How should it allow the social hierarchy, which is only a clumsy image of it, to go on existing?”

Absent an absolute reorientation, lacking what Dorothy Day called the revolution of the heart, “business is business.” The bourgeois spirit will continue to find the kingdom of heaven unbearable—an otherworldly reign that ought to be tempered, tamed, reinterpreted until Christians can find themselves full at home with the spirit of capitalism, and this in spite of the fact that, as the Vatican newspaper Osservatore Romano contended even in 1949, “Capitalism is intrinsically atheistic. Capitalism is godless, not by nature of a philosophy which it does not profess, but in practice (which is its only philosophy), by its insatiable greed and avarice, its mighty power, its dominion.” Dawson closes “Catholicism and the Bourgeois Mind” with the following lines: “If the age of the martyrs has not yet come, the age of a limited, self-protective, bourgeois religion is over. For the kingdom of heaven suffers violence and the violent take it by force.” Regretfully, the Catholic historian was utterly wrong in his proclamation that the age of bourgeois religion is over. He was, after all, only human. A historian and not a prophet. But perhaps he was also wrong in his assessment that the age of martyrs has not yet come, and this not merely in the sense that the twentieth century saw a staggering number of Christian martyrs. Rather, as Raïssa Maritain observes with regard to Bloy’s death, “We saw this peace and this wonder on his face in the very last hours of his life. The martyrdom of blood would have been in his soul the illumined symbol of the constant martyrdom he had suffered during long hard years in which his life and labors had no other aim than to give witness to Truth and Faith and the exigencies of God.” By his constant martyrdom Bloy bled drops that can still serve as seeds that might grow in the soil of contemplative souls who have grown dissatisfied with the comforting confines of the bourgeois mind. A mind many in the Church have too long tried to baptize. A mind that can only be baptized by the blood of the poor. A mind that, baptized, all too soon assumes holy orders and presides over the funeral of our immortal souls.

*Author’s note: Wiseblood Books will publish the first English translation of Léon Bloy’s Exégèse des lieux communs in January of 2021.

Really superb! And I hope it’s not too late to send accolades regarding your previous article here at FPR which was excellent as well, as both reward the close attention and energy-in-reading they demand. I have a picture of Bloy above my desk and remember Maritain saying that it (his face) was “cut like a stained glass window”. This is the best piece on him I’ve read. Robert Calasso references Bloy in numerous places and I suspect his influence on Calasso is bigger than, perhaps, he lets on as Bloy is one of the few who give us a ‘peak behind the curtain’ of modernity Calasso explicates in his own monumental way. Might I add one more title, in addition to “Pilgrim of the Absolute” and “Thankless Beggar” he used in reference to himself that also shows his personality a bit? The “Sheepdog of the Fold”. It captures, as you do, both his ferocity and his love. Thanks again. I will be ordering your book.

I haven’t read Bloy, or much critique of the bourgeois at all, to be honest, but I wonder how this jibes with the current concern for the squeezing/shrinking of the middle class, specifically the lower-middle “working class.” In contemporary terms are the bourgeois limited to the upper middle class?

Comments are closed.