Caldwell, ID. Back in March, the coronavirus pandemic hushed once bustling streets into what The New York Times named “The Great Empty.” By April, the American unemployment rate was at a peak of 14.7 percent. Late May and early June saw streets erupt with protests, riots, and looting following the brutal killing of George Floyd. In this first half of 2020, main streets across the globe have witnessed extremes that make 2019 seem quaint.

But what of Wall Street, that most influential of American streets? After near catastrophe in late March, markets rallied. Unemployment rates and markets rose together—fostering a renewed suspicion among many that Wall Street’s gain was Main Street’s loss—until May, when states started to re-open and jobs started trickling back. This trend continued in June, with the unemployment rate dropping to 11.1 percent. These gains appear tenuous, however, given fears about the future course of the pandemic, political reactions to it, the 2020 election, and an increasingly frayed social fabric. On this 244th Independence Day weekend, American main streets still face great uncertainty.

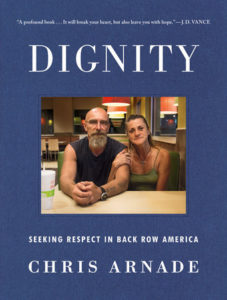

To discuss Wall Street and Main Street in more nuance, this month’s Brass Spittoon brings together three newcomers to Front Porch Republic. Chris Arnade is a freelance writer and photographer and the author of Dignity: Seeking Respect in Backrow America. He has a Ph.D. in physics from Johns Hopkins University and worked for twenty years as a trader on Wall Street before leaving Citigroup in 2012 to document addiction in the Bronx. Jared Woodard works in financial services in New York and holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from Fordham University. Finally, economist Sarah Hamersma is associate professor and Ph.D. director in the Department of Public Administration and International Affairs at Syracuse University and a contributing editor for Comment.

Stewart: In what ways do you think the Wall Street versus Main Street narrative is valuable, and in what ways is it misleading? What does it reveal? What does it obscure?

Arnade: It is valuable in that it captures the fairly sizable gap in power between large global conglomerates with access to financial markets and their shareholders versus smaller, community-based companies and the average consumer.

That gap is reflected in how policy is constructed in the first place, with Wall Street having more recourse to influence favorable policy because they get directly heard and have a direct line to writing policy.

The result is a “bail-out system” built to favor them. The Federal Reserve can bail out Wall Street quickly because it can buy any publicly traded security. By definition, that gives Wall Street a detour around the messy political process Main Street has to go through to receive help. The result is what you saw in 2008: crisis management that at almost every juncture favored Wall Street. Put simply, our financial plumbing is built to give Wall Street water first. The other defining difference is that Wall Street’s focus is global, while Main Street’s focus is, well, local main streets. The result is that Main Street residents, from the small businesses to mayors to homeowners, have an equity stake in the health of their own community.

Wall Street has an equity stake in the health of the global economy and can be largely indifferent to the decline of any one town or neighborhood, or even a whole collection of communities. That is a massive difference that influences how our national macro policy—from trade issues to labor issues to environmental issues—is shaped, given Wall Street’s outsized influence.

What is missing in this framework is the diversity of Main Street, especially those consumers who are outside of the system. Those are the many people I write about, who, for instance, don’t have access to a banking account. They don’t have an equity stake in Wall Street or Main Street, so are left out of almost all conversations. They are the ones who are hurt most by any crisis, and the ones who generally are not even considered when we shape policy, except to be dealt with in negative terms.

What is missing in this framework is the diversity of Main Street, especially those consumers who are outside of the system. Those are the many people I write about, who, for instance, don’t have access to a banking account. They don’t have an equity stake in Wall Street or Main Street, so are left out of almost all conversations. They are the ones who are hurt most by any crisis, and the ones who generally are not even considered when we shape policy, except to be dealt with in negative terms.

Woodard: There’s been an intentional restructuring of the US economy over the last several decades. Ordinary people keep working harder and becoming more productive, but they keep less and less of what they produce. In some sense that’s an old, familiar story, and if “Wall Street versus Main Street” is just shorthand for capital versus labor, it’s apt. An interesting wrinkle in the story today is the fact that rampant inequality is hurting not just the workers on Main Street, but increasingly the businesses they work for, whether small local firms or global corporations. When more and more capital is held in fewer hands, it creates a vicious cycle in which those pools of capital chase increasingly scarce global demand. For example, over the last eight years, spanning two presidential administrations, the profits of US technology firms have grown by 94%; for the rest of the US economy, profits actually fell 2%.

The problem is that many national economies have been restructured, via explicit political choices, to favor short-term gains without regard for long-term costs. We rewrote laws to favor quick profits from using cheap global labor without regard for the painful costs to local communities. We stopped investing in basic research, local industries, urban development, and all our people for the sake of illusory promises of greater riches abroad. Now we are dependent on our strategic rivals, not just for pharmaceuticals and PPE, but for a huge list of industrial goods, many necessary for national defense, with nothing to show for it.

Hamersma: I’m both temperamentally and professionally inclined to avoid framing the economy in terms of competing players. The most fundamental insight of economics is the notion of mutually beneficial exchange: each of us can help the other by trading goods we are particularly skilled at providing. There is not a winner and loser in a voluntary transaction, but two winners. While I can (easily) be convinced that one group is getting more out of a transaction than another—for reasons from power dynamics to demand or supply conditions—it takes a strong argument to convince me that participation in a market economy involves “givers” and “takers.”

Since economists don’t generally use this kind of narrative, it may be that I don’t fully understand the players, so I think I’d best define my understanding of the terms before giving my other (hopefully relevant) thought. As I understand it, Wall Street seems intended to conjure images of wealthy stock traders and CEOs who are unfamiliar with the cares of daily life, as well as their “corporations” that seem to be an evil actor in their own right. Main Street, by contrast, seems intended to represent people who go to work, take care of their families, and pay for their food and home with each paycheck as it comes.

What strikes me as odd about this narrative is that it fails to acknowledge that the two groups are usually part of the same ecosystem. The corporations in the “Wall Street” image are the employers of many, many Main Street people—in fact, they employ many more of them than locally-owned establishments. In recent years, less than 17% of private sector workers work in firms with fewer than 20 workers. In contrast, nearly half were employed by firms with 500 or more workers. By a huge margin, most people work for large firms. It would appear that Main Street’s paycheck often comes from Wall Street. The fate of Main Street is more closely linked to Wall Street than this dichotomous narrative tends to imply, at least in the short run.

Stewart: The perception that Wall Street was bailed out at the expense of Main Street following the 2008 recession is widespread and contributed to the growth of new forms of populism on both the left and right. Granted that there was not a pandemic in 2008 and that the situations are different in other ways, what are the most significant similarities and differences between the bailouts of 2008 and 2020? Thus far, have these populist impulses managed to prevent a re-enactment of 2008?

Arnade: The huge difference is that “nobody caused this crisis.” The 2008 crisis was caused by Wall Street’s greed, only then to be bailed out while Main Street suffered. I fully believe that particular injustice is behind a lot of populism today.

This crisis is very different. It isn’t anyone’s fault, and so there isn’t a clear group to blame. I have actually been impressed with our policymakers’ response so far; it has been a lot more equitable than in 2008. That is partly due to those in power having listened to the critics and changed. That is a very good thing! So, yes, the populist impulses that surged post-2008 have helped shape better policy.

Yet this pandemic has revealed how unjust our society is, despite the good policy response. It is in many ways the tide that goes out, revealing a lot of ugly stuff. Good policy can’t fully obscure the ugliness it has exposed, like the large inequalities we have across race, place, and gender. What once was unseen by many, like the Laundromat gap—some people couldn’t shelter in place for two months—have been seen and felt. Or the essential worker versus those who can work from home. All those inequalities already existed, they just became more visceral and harder to ignore.

Woodard: The biggest problem with policy efforts after 2008 was that they were too small… miserly, really. Instead of providing a backstop for the whole economy and making investments in infrastructure, the industrial base, R&D, and healthcare, in September 2008 the House of Representatives rejected the first package and was prepared to let the world burn. Then, when Congress finally came around, they saved the financial system but not the rest of the economy, leaving the Federal Reserve to do all the heavy lifting in the years afterward, a task for which it is not well-suited.

The biggest difference between 2020 and 2008 is that Congress seems mostly to have learned the lesson. This year we enacted the largest fiscal expansion in the history of US peacetime. In May, ordinary wages plus stimulus checks meant that, in the aggregate, household incomes actually matched the level from before the pandemic hit. Of course, that income is very unevenly distributed and more support will be necessary, but it’s a far better outcome than during the last crisis.

Hamersma: It seems to me there is one fundamental difference between the 2008 and 2020 situations that ought to drive the difference in design of bailout packages, and it is this: in 2008, consumer demand collapsed because people could not afford goods and services due to lost wealth and jobs, while in 2020, demand collapsed because many goods—and especially services—were at least temporarily no longer for sale. In other words, the second collapse was more mechanical: transactions were prohibited by government order for public health reasons. Put differently, the 2008 recession was a market correction—partly from a real estate bubble—whereas the 2020 recession is not mostly a correction but the artificial interference of an exogenous shock in the form of a deadly and extremely contagious virus. Both brought about job losses, but the two are really not comparable in terms of thinking about solutions.

In 2008 one could make the argument that certain losses simply needed to be taken—that intervention would prop up something that simply wasn’t sustainable in the long run due to changing economic dynamics. This is part of why huge bailouts that ended up going to shareholders (through stock buybacks) were so upsetting to the public. In 2020, the best solutions must involve bailouts, because even businesses with “good bones” and economic prospects suffered a major, costly disruption. My favorite proposals for a bailout involved maintaining employees’ attachment to their firms while not working, i.e., bailouts to cover payroll when employees couldn’t actually generate any revenue for the firm to pay them with. Variations on this came from Steven Hamilton and Stan Veuger and the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Subsidizing payroll substantially reduces the government burden of unemployment benefits to those workers and would allow for the market to jump back into action more quickly upon re-opening (not to mention adding the psychological benefit of being furloughed with pay rather than being laid off).

This job-protection notion did not ultimately feature prominently in the bill, however, despite the efforts of economists. The bailout that ultimately passed included greatly expanded unemployment benefits as well as direct payments to workers—including (inexplicably) those whose jobs and incomes were fully intact—announced to each household in a letter from Donald Trump himself. The portion provided to corporations—which forbids the stock buybacks that were so troubling in 2008 and does provide some payroll subsidies—is under fire now, though I don’t think the dust has cleared enough to make a call on how it will compare to 2008 in its effects.

Stewart: The pandemic has brought new attention to the liabilities of global supply chains, even as it has also made it even harder for the businesses that might help replace such global industries to survive. Is there any chance Main Street benefits from a renewed commitment to local production, or are we looking at a world dominated even more by Google, Amazon, and Walmart?

Arnade: I want to believe this will refocus our energies towards smaller businesses that are building blocks of local communities and away from global conglomerates whose priority is profit over community health. I am not sure it will though. Big companies are not going to give up their source of cheaper labor. Also, to be fair, global conglomerates like Amazon and Walmart have also shown to be very useful in the new pandemic economy, one that is less about physical interaction. I would hope we could meld the two — the advantages and conveniences of Amazon and Walmart, with the local community stakes that smaller businesses have. To move towards a business framework where being “good members of both your community and nation” takes equal footing with profits.

I am not hopeful though. I think the global supply chain worries that have been exposed, primarily in things like medicine, will end up being manifest more as ugly anti-foreigner politics than as “let’s refocus policy to make it more conducive to local community health.” To conclude, there is simply no denying that Amazon and Walmart have shown themselves useful in the pandemic, and I think that is going to be hard for people to forget. We tend to think in binaries, rather than smaller adjustments in our policy.

Woodard: On this point there are reasons for hope for the first time in a long time. During the era of peak globalization, roughly 1980 to 2015, unchecked flows of goods, labor, and capital meant slower economic growth, precarious employment and social disruption. Today, there are some signs that a transition is beginning. In 2019 we saw a 1 percentage point jump in the share of US domestic manufacturing output relative to low-cost Asian producers, reversing 20 years of steady declines.

The focus is shifting away from financial engineering and toward real productive investment. We know that every new durable goods manufacturing job creates 7.4 new jobs in other industries. For every $10 billion of manufacturing revenue brought back home, companies tend to increase domestic investment by another $4 billion. And when it comes to research and development, the benefits are even more glaring: economists have found that every $1 of public investment in R&D generates $8-9 of GDP. In other words, these kinds of investments pay for themselves many times over, with incredible knock-on effects for the real economy. Working people want this, and professional investors want this too—they see the need for a more diversified, more resilient economy.

The good news is that appreciation is growing among policymakers in both political parties for the importance of domestic industry. In a recent survey of pending legislation in Congress we counted more than 20 bills designed to boost public sector R&D and to incentivize corporate investment in property, plants, and equipment. One bill would provide $100 billion for science and new research; another would give big incentives for business investments and to rehire workers laid off during the pandemic. A big resurgence of local production and broader, faster economic growth are achievable, but only with a sustained political realignment. Whether this realignment continues is the crucial question.

Hamersma: While people at the moment are supporting locally-owned businesses as they fear losing them permanently due to the COVID-19 crisis, there are a couple of reasons I don’t expect long-term benefits for them. First (by a large margin), they are often more expensive than their chain-based counterparts. While people who have steady income can afford to give extra support at this point in time, I don’t see the extra spending being maintained when people have opportunities to once again do other things with their entertainment, travel, and leisure budgets.

Second, Amazon has made it possible for us to safely lock down in our homes much more easily than in its absence; while there has been an ugly corporate underbelly revealed, the fact that they have kept so many people supplied with their needs (and wants) during this time suggests to me that they are very much here to stay. I think Walmart is similar in providing staples during this time.

Given that, I want to provide a couple of upsides of the continuing presence of large retail firms. Returning to my comment above, most people work for large firms. Walmart is a very important employer in the retail sector, and while shopping there may involve trade-offs and other concerns, it is not inconsequential that they pay the wages of hundreds of thousands of Americans whose best current option is that Walmart job. Economists call this “revealed preference”—if there were a better available job option, whether at a locally-owned place or elsewhere, they would surely take it. Now, does this mean the Walmart job is satisfactory? Not necessarily. But I think this insight should affect our response to the dissatisfaction we feel with their outsized role. If we are concerned about labor practices or product quality, there are (admittedly difficult) legal and regulatory paths forward. If instead we try to solve the issue by refusing to buy from them, it is unlikely to help local workers (who may face cuts in hours or lost jobs if demand falls). Add in the fact that large firms often have the scale to make necessities affordable to low-income families, and in general, I prefer to think about improving rather than trying to starve large firms.

Photo courtesy of Matt Stewart. 7th and Main, Caldwell, Idaho.

Three PhDs from NY. Thanks, FPR editors, you really have your pulse on 2020 America.

Spoken from apparent ignorance. I don’t know Woodard and Hamersma but Arnade is far from an ivory tower PhD. Read his book. (Which would have been huge had it been able to be used as a cudgel against either DT or the liberals exclusively. Since it cuts both ways a lot of people who should know better ignored it.)

Don’t leap to attack for no reason. You’re the ignorant one. I’ve followed Arnade’s twitter feed for years. I’ve read his book. Posted about it many times in threads here when it was first published. I even said your parenthetical comment there. Heck, you probably stole it from me. He’s great. And guess what–he has a PhD and has worked and lived in NY his whole adult life.

LOL. I was right. You did get that from me:

https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2019/06/blessed-are-the-working-poor/

Ok, so why the hatin’ ? If you know and love his work your snarky comment against FPR makes no sense, since you know he’s a writer who certainly has a finger on the pulse of 2020 America.

You’re right. I should have said “Chris Arnade is great, but seriously FPR editors, you should do better than put together a panel of three PhDs from NY if you’re trying to show you really have your pulse on 2020 America.” Instead I went with short and snarky. In my defense, it’s because the internet is an evil brain melting horror show that is causing modern civilization to melt down right in front of us.

That’s coincidental on an awesome scale. I knew I picked it up somewhere but didn’t know where — I thought it was maybe from an Amazon review.

In case it’s helpful, I’m a Midwesterner, married to a Canadian, schooled in MN, MI, and WI. First job in FL. Moved to Syracuse, NY 7 years ago. Not even slightly qualified to be called a New Yorker 🙂

Sarah (“Economists call this “revealed preference”–if there were a better available job option, whether at a locally-owned place or elsewhere, they would surely take it”) Hamersma, meet Tom (“No One Makes You Shop at Wal-Mart“) Slee.

Thanks! Always happy to engage in a conversation. There are definitely challenges associated with the long run that I could not address in this short piece, but are part of the larger conversation.

Comments are closed.