Mill Valley, CA. As our country struggles to come to terms with its racist past—and present—a controversy surrounding a 1934 mural at the University of Kentucky mirrors the racial tensions of today.

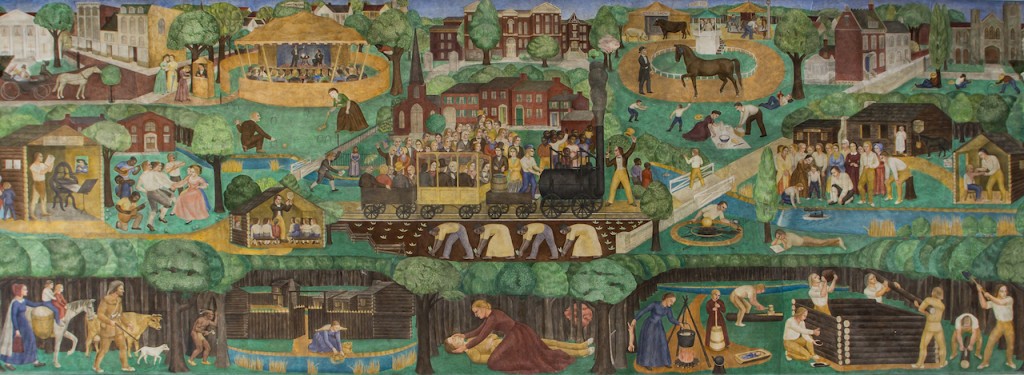

Ann Rice O’Hanlon’s New Deal-era fresco, a jewel-like composition alive with historical vignettes of the Lexington area, has long troubled Black students for its depiction of slavery. Calls for its removal had intensified in the last five years, but it also had its champions. Because a fresco, a painting consisting of many layers of color painstakingly applied to fresh plaster, is fused to the wall, removal is problematic to say the least. It can be erased—painted over—or hidden beneath panels with the hope that one day it can emerge, but the options are limited.

Journalist Linda Blackford, who has been covering the debate in the Lexington Herald-Leader, wittily termed the fresco “a plaster strip-tease artist with the number of times it’s been covered, uncovered, then covered again.” Its first cover-up happened in 2015 after UKY President Eli Capilouto met with concerned students who considered the work racist and its images of slaves both painful and “sanitized.” A VIP task force was appointed to come up with a proposal regarding the fresco’s future and to make recommendations for how the university could improve the conditions on campus for all people of color.

Reaction was swift. UKY alumnus and author Wendell Berry, whose wife Tanya is Ann O’Hanlon’s niece, wrote an op-ed accusing Capilouto of “overcooked political correctness” in covering up the mural. He suggested that to depict slavery in a painting in 1934 had to have taken some courage. “Ann was a liberal, if anybody ever was—too liberal, in fact, to approve entirely of me. I never heard her utter one racist word,” he wrote.

The National Coalition Against Censorship, an alliance of non-profit organizations including literary, artistic, religious, educational, professional, labor, and civil liberties groups, urged the university to preserve the mural and continue to display it with added information to place it within a broader context of the state’s and the nation’s history of slavery.

The task force report, submitted in 2016 after months of deliberations, recommended that a diverse group of artists of color be commissioned to produce representations “to be in dialogue with the mural.” O’Hanlon’s fresco would be uncovered, this time accompanied by new, contextualizing signage. Increased programming in Memorial Hall, including discussions, classes and events, would focus on race and identity from many perspectives.

In June of 2018 Philadelphia artist Karyn Olivier, originally from Trinidad and Tobago, was chosen to create a mural in the domed ceiling of Memorial Hall’s vestibule. She chose to replicate the Black and Indigenous figures from O’Hanlon’s fresco on a gilded background. She interspersed portraits of Black heroes and heroines and stenciled quotes, including one by Frederick Douglass: “There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.” Her glowing mural, Witness, unveiled that August, attracted admiration for its beauty, but it did not appease the critics.

In April 2019, students from the Black Student Advisory Council and the Basic Needs Campaign held a sit-in and food strike in the university’s Main Building to seek action on multiple demands for change at the university, including removing the mural. It was covered once more with curtains. Soon after, the administration announced it would close Memorial Hall to any required classes starting in the spring of 2020, ensuring that students who were offended by “the building’s central mural that depicts early Kentucky history with black and Native American stereotypes” would no longer be forced to see it. And there the matter rested. Temporarily.

Ann Rice O’Hanlon (1908-1998), a native of Kentucky who settled in California as an adult, was fiercely independent with a philosophical bent and socially progressive views. Born in Ashland, the oldest of five children, she always knew she wanted to be an artist, and her ambition was encouraged by her parents, Jewell Rice, a lawyer, and Matilda Rice, a homemaker who sold beaten biscuits from her kitchen to make ends meet.

Raised mostly in Lexington, Ann Rice was never completely happy in Kentucky. There was much that she loved, but the cultural life felt restrictive. She was unhappily aware of the Jim Crow laws that kept the races apart and marginalized Black Kentuckians, and the art scene at the university, where she was an undergraduate, was too conventional for her taste. She helped put herself through school by painting ancestor portraits for clients and “escaped” (her word) soon after graduation to attend graduate school at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. There she met her future husband, Dick O’Hanlon, a young sculptor from Long Beach, California. Diego Rivera was in residence, painting a fresco on one of the school’s interior walls, with Dick as his plasterer, a skill that would come in handy later. In 1932 Ann and Dick married, and they decided to stay with her parents back in Kentucky for a while. They had no money and few prospects.

As luck would have it, a new federal program was being established to extend relief beyond industrial and agricultural workers to the professional class during the Depression. The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), America’s first federal government program to support the arts nationally, was paying artists to decorate buildings and parks. Ann was tapped by her former UKY professor, Art Department head Edward Rannells, to create a fresco at the university illustrating “The American Scene,” the theme PWAP had selected. She would be paid $38 a week, a decent income in those Depression years. Because no other plasterer was available, Dick was chosen by default to do the job. Ann chose a high, long wall in the school’s Memorial Hall as the site. The finished fresco would be thirty-eight feet long and eleven feet high. It was one of forty-two frescoes funded by PWAP, the largest in Kentucky and the only one by a woman.

Ann and Dick threw themselves into research, focusing on the Lexington region, and then she worked out a scheme of continuous events interwoven over the wall’s surface, like a group of Persian miniatures. Rannells approved the plan and the project began. Dick rose every night at midnight, went downtown for coffee, then mixed and applied fresh plaster to the section of the wall his wife would paint the next day. She arrived in the morning and worked, applying color in twenty to thirty layers while the plaster was still damp. They rarely saw one another in the eight months they spent on the project.

The focal point of her mural is a reference to slavery: four bent-over figures, two men and two women, toiling in a tobacco field. They bring to mind figures in Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, a painting Ann would have known. Elsewhere, three Black musicians play for white dancers; and African American men, women, and children watch from the periphery as white people engage in celebratory activities. The mural, for all its gay colors and references to inventions and innovations, speaks of exclusion. The parallel, impressive history and accomplishments of Black Kentuckians are not included, whether to further her point about exclusion or out of ignorance. Did she know anything about the early history of the Kentucky Derby, that the major trainers and jockeys were Black? Did she know about Robert H. Gray, the Black Lexingtonian whose patents included a Baling Press in 1894 and a Cistern Cleaner in 1895? Had she heard about the Negro Chautauqua in nearby Owensboro, founded in 1906 and hugely successful in the African American community, to which the journalist Ida B. Wells drew a crowd of 1,200 in 1910? When she painted her vignette (much criticized) of an Indian man watching a white woman draw water from a spring—a reference to the Siege of Bryan Station in 1782—did she realize that there had been Native American habitations in the area for thousands of years? Chances are that the history books she and Dick studied only included the accomplishments of white people.

During the eight months they worked on the fresco, it attracted very little attention. In a 1964 interview for the Archives of American Art Ann addressed this lack of interest:

It wasn’t traditional portrait painting, [so] the townspeople couldn’t have cared less. The audience that was curious, about what was going on and about the nature of the fresco in general, its design and the way it was being done, were the Negro janitors at the university. They were fascinated with the whole process and they would ask endless questions about it, whereas the interest on the part of [the] white population there was just totally devoid of curiosity and had only to do with the events—the literal aspect of the events that were going on the wall…. They would come in every night and watch me paint and sometimes bring me apples or Coca-Colas. They were just delightful people to keep my spirit up and believe me, at times it waned very much.

It’s intriguing to imagine incidents in the mural that might have been inspired by stories those gentlemen told. A Black youth who has climbed a tree to listen to music or a lecture coming from a white Chautauqua tent could be one. A memory of two Black young people watching a white boy fish from a bridge, another scene in the fresco, could have been shared. These things are unknowable, but what is certain is that the inclusion of Black people in her fresco was important to her.

History is multilayered, and each layer tells a story. The university was segregated at that time and would be for another fifteen years. But Kentucky, as so many other regions in the United States, was built on the backs of slaves, and Ann made sure that message was embedded in her fresco.

An artist’s intent in a work is essential in interpreting that work. Knowing that intent provides a ballast that we should weigh against the concerns of the present. The aesthetic quality of the O’Hanlon mural is undisputed, but each generation will view the artwork differently, and the artist’s intent will pale in comparison to the way it is perceived in a given political climate. What was barely noticed in 1934 may offend in 2020. And in 2025 it may not offend at all. We must learn to live with different points of view because we’ll never agree about everything.

Their intensive efforts in Memorial Hall left the O’Hanlons exhausted and eager to be gone. The day the fresco was finished they left Kentucky for some rest and recuperation in New York before returning to California. In 1942 they purchased a former dairy ranch in Mill Valley, twenty minutes north of San Francisco. They remodeled the barn into a home and studios and began their teaching careers—Dick at the University of California, Berkeley, and Ann at Dominican University, where she co-founded the Art Department. Her greatest passion was the study of perception—how we see, and how we can train ourselves to see more deeply. For the rest of her life she taught classes in art and perception, influencing countless students and inspiring scores of older people who longed to explore their creative selves for the first time. The non-profit art center she and Dick founded in 1969 continues her work.

In the 1964 interview, she confessed that after finishing the fresco at the University of Kentucky, “I was just tremendously disappointed with it. I felt as though I’d done a tremendously horrible thing to the people of Lexington. I guess that’s normal. Is it? I don’t know. But when I went back to see it after five years or so, I was rather surprised. It was quite jolly and it had a sparkle that I hadn’t remembered existed because I . . . had been too close to it and now that I’m completely detached from it in ways of working and attitude toward painting . . . I enjoy very much looking at it.” Her mural is multifaceted; there is always more in it to contemplate. It’s a period piece, a piece of history, and it is worth saving.

The saga continues. Days after the murder of George Floyd by a police officer, President Capilouto announced that the university would remove the mural altogether. A spokesperson added that the university would begin looking at the best way to do that. Karyn Olivier, who has studied O’Hanlon’s fresco intimately, protested in an op-ed in The Washington Post that its removal would render her own artwork mute.

Christopher Finan, director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, wrote President Capilouto asking him to halt his plans, claiming it would negate Olivier’s work: “This is the first instance we are aware of in which the removal of a mural by a white artist will have the simultaneous effect of silencing the work of a Black artist. We urge you to reconsider your decision to remove the mural and to instead pursue the University’s original goal of engaging in the sustained, difficult and complex conversations that can arise in contemplation of these old and new works.”

Wendell and Tanya Berry filed a lawsuit against the university, arguing that because the fresco was created through a government program, it is owned by the people of Kentucky and cannot be removed by the university. The suit, which is pending, also asked for an injunction to prevent President Capilouto from taking any action to remove the mural while the case proceeded.

University spokesman Jay Blanton responded to the Berrys’ suit by releasing a statement that asserted in part, “Moving art . . . is not erasing history. It is, rather, creating context to further dialogue as well as space for healing.” He failed to explain how empty space vibrating with the afterimage of a contested artwork creates healing.

As well-meaning as she surely was, Ann O’Hanlon’s perspective on history was limited. New perspectives are needed to balance and augment her mural. Karyn Olivier’s Witness was just the beginning.

Olivier has said her goal in creating Witness was to ask “Is it possible to hold opposing ideas and realities in one hand? Can we harness the tough questions they raise to wade into the pain, complexity and frightening histories of America, and consider the possibilities and resilience of black and brown people?”

The answer should be a resounding YES.

~~~ensuring that students who were offended by “the building’s central mural that depicts early Kentucky history with black and Native American stereotypes” would no longer be forced to see it.~~~

What burns me about this episode and most of the similar ones is the evidence of sheer hypocrisy. For decades liberals have been responding to religious people and conservatives who complain about the offensive nature of various art works, music, TV shows, etc., with some variant of “It has an on-off switch, doesn’t it? No one’s forcing you to watch it.” The examples of these sorts of responses easily number in the thousands.

But we see that when the shoe is on the other foot the artistic former libertines refuse to abide by their own recommendations. No, the things cannot be simply ignored or bypassed — they must be covered or torn down or disclaimed to death or otherwise obscured. It’s not their “message” that’s objected to, it’s their sheer existence.

If American universities and other stewards of public spaces were doing these same things in regards to art that offends conservatives and religious folk you would literally never heard the end of it. There would be no escaping the cries of “Censorship!” and the loud defenses of freedom of expression.

For me this is simply example no. 243,967 that liberal/progressive “tolerance” is an utter sham. It amounts to “tolerance for thee but not for me,” which is in fact no “tolerance” at all.

My PhD in History is from UK, and I paid some attention to this saga, while I was there, in the early 2000’s. I was a TA in the classroom that’s right on the other side of the wall that the mural is painted on.

What stood out to me, and now, as I’ve discussed this ongoing affair with my own students when I teach philosophy of history, is how right Nietzsche was, when he argued that the act of living requires forgetting, as well as remembering. People who think we should get rid of historical monuments think they’re thereby “putting it behind us.” In fact, all we’re doing is ensuring the opposite.

Aaron

Comments are closed.