“Our Humanity Depends on the Things We Don’t Sell.” In a profound essay, Mary Harrington links such apparently disparate topics as strip-mining, prostitution, and enclosure to defend the ordinary work of caring for our fraying relationships:

To see the world in terms of standing-reserve means seeing it as transactions rather than relationships, and information rather than meaning: as Heidegger puts it, “shattered,” and confined to a “circuit of orderability.” This shattered world is the same one the market society mindset calls ‘open’: openness to new forms, after all, means weak adherence to existing ones.

“Pope Francis’s Call to Fraternity.” Austen Ivereigh summarizes the arguments and significance of the Pope’s new encyclical, Fratelli tutti. Among other subjects, Pope Francis tackles the tensions between the local and the global: “he is no unthinking globalist: the local has something the global lacks, and only the well-rooted can reach out to the other. The local and the global are in polar tension, but they are not antithetical: what is needed is a ‘healthy relationship between love of one’s native land and a sound sense of belonging to our larger human family.’”

“Third-Culture Kid.” Eric Miller describes the experience of being profoundly formed by different places, each with cultures that drew out different aspects of his personality.

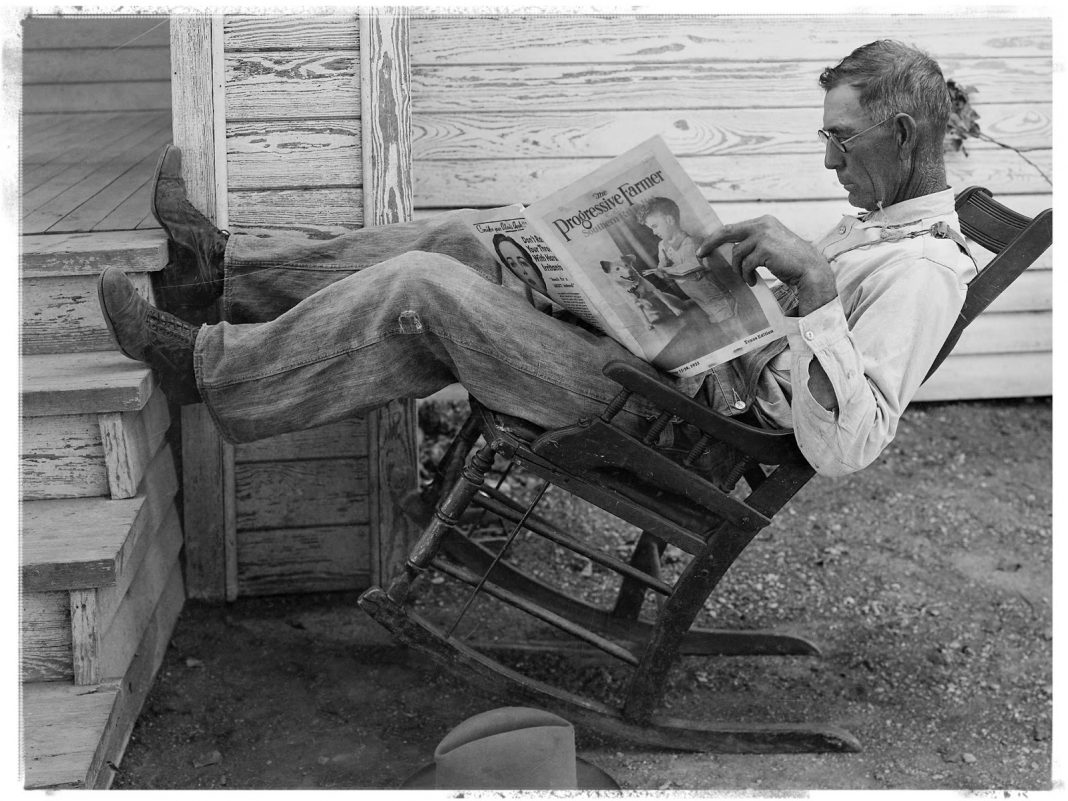

“The Colour of the Soil.” Gracy Olmstead delves into the fraught, and painfully racist, legacy of the Southern Agrarians. As she notes, it can be hard to comprehend the “mental gymnastics” required to critique exploitative industrialism while defending plantation farming and racial slavery. Reading their work and wrestling with these contradictions, however, might engender humility, prompt reflection about our own blind spots, and inspire the kind of work Gracy undertakes in this essay as she delineates a more just agrarian tradition.

“Can Hierarchies Be Rescued?” Chang Che reviews recent books that praise aspects of China’s Confucian respect for hierarchy. As he argues, there are some social goods that can only be realized in hierarchical relationships.

“Not Catholic Enough.” Next week FPR will be running a review of Jason Blakely’s new book. This past week, Blakely published a lengthy critique of Adrian Vermeule’s integralism.

“America Is Broken.” In a long essay for the Atlantic, David Brooks chronicles why Americans no longer trust one another and how that trust might be restored: “The shift toward a more communal viewpoint is potentially a wonderful thing, but it leads to cold civil war unless there is a renaissance of trust. There’s no avoiding the core problem. Unless we can find a way to rebuild trust, the nation does not function.”

“‘Witty, perceptive, provocative’: President Leads Tributes to Poet Derek Mahon.” The Northern Irish poet Derek Mahon passed away. The Irish Times has published a series of remembrances. (Recommended by Richard Russell.)

“Manage Forests for Timber, not Tinder.” Holly Fretwell and Jack Smith recommend new timber harvesting practices that would reduce fire risk. Their proposal shares some features of the “worst first” harvesting Wendell Berry has recommended; there are good ways to manage forests that don’t entail clear-cutting them or leaving them untouched and vulnerable to wildfire.

“‘The Coal Industry is Back,’ Trump Proclaimed. It’ Wasn’t.” In a long essay with haunting photos, Eric Lipton narrates what happens to two communities where massive coal plants and mines shut down.

“Summer of the Statue Storm.” A.E. Stallings reviews Susan Stewart’s The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture and ponders the meaning of monuments and memorials, ruins and words.

“A Wisdom that is Woe.” Joseph Keegin responds to new books by George Scialabba and Zena Hitz (watch FPR next week for an excellent review essay we’ll be publishing that puts Hitz’s book in conversation with another new book) and suggests that intelligence and contemplation are not unmitigated goods:

Thinking is at best a liability, something that destabilizes the solidity of a life and rips one from fellowship of other people. At worst it’s poison, a fatal and ineradicable dose of melancholy and doubt. In either case, the only rational course is to avoid it.

“Congress’s Big Tech Report Shows Why Anti-Trust History is so Important.” Ron Knox situates the recent congressional report on tech monopolies in the longer history of American monopolies and trusts.

“How Louise Glück, Nobel Laureate, Became Our Poet.” Dan Chiasson praises Glück for the years of attention she’s given to her students:

Glück—like the last American woman to win the prize, Toni Morrison—is a teacher, a sage for thousands of students at a variety of institutions, from Goddard College, in its hippie prime, to Williams, Yale, and Stanford. “Teaching,” for figures of her calibre, is often a word that means giving scripted lectures and then fleeing into the wings, or charging mega-dollars for a sun-drenched guru experience at a resort. Glück is a classroom teacher, at home in a small group, around a table.

“An Interview with A.M. Juster.” Trinity House Review interviews Juster about his new book, the work of translation, and political poetry.

I love Gracy but I fear she’s overreacting about I’ll Take My Stand. Berry somewhere says that while there’s racism in the book, it’s not a racist book. He states that you could remove the examples of racism that appear there and not fundamentally change the book’s arguments. This has always been my take on ITMS since I first read it some 15 years ago and in several subsequent rereadings.

I do not believe it is a good thing to allow current sensitivities to shade unnecessarily our readings of past figures, arguments, etc., lest we find ourselves inescapably and therefore invalidly condemning people of older times by 21st century standards, and often suspect ones at that.

To take but one example from her piece, Gracy calls out Andrew Lytle for using “the n word” in his essay. She does not seem to understand how common that word was in 1920’s America, both North and South, and that it was not always used viciously. This, of course, does not make it right, and it is indeed unfortunate that the word was in somewhat common parlance. But the fact remains that while the word is definitely a “thing” nowadays, it was not the same sort of “thing” in the 20’s, and it is unfair to condemn Lytle for using it as if he wrote his essay yesterday rather than in 1929. Because the word has undeniable associations with malice in 2021 does not mean that we get to read those associations back onto an author who was writing a hundred years ago. Do we assume malice on the part of Wodehouse because he used the word occasionally? Or on Conrad because he included the word in the title of one of his novels?

I have no argument with the idea that the legacy of the Agrarians is “fraught,” as Jeff says. But I’d argue that judging our ancestors by 21st century measures is equally fraught, for who among them will remain standing?

Comments are closed.