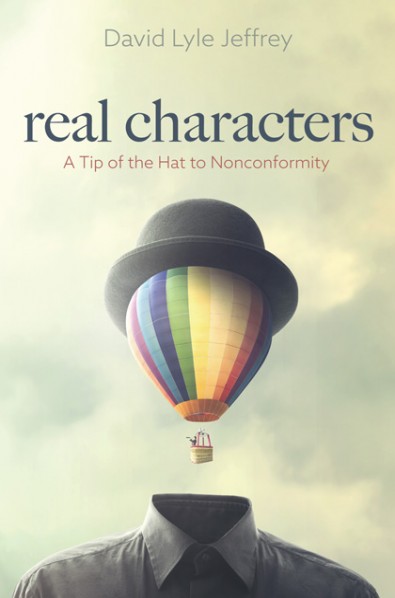

The newest title from FPR Books is Real Characters: A Tip of the Hat to Nonconformity by David Lyle Jeffrey. This is a delightful book of humorous stories and hard-won wisdom. Scott Moore commends it this way: “Whether in the Ottawa Valley of his youth, the ivory towers of Princeton, or a Florentine trattoria, David Jeffrey shows that the Front Porch Republic isn’t just limited to American small towns or rural homesteads. Porchers everywhere will want to ‘sit a spell’ with Jeffrey for his delightful and moving stories of the ‘real characters’ who made him the man he is.” You can get your copy here. While you’re waiting for it to arrive in the mail, enjoy the introduction.

It will be apparent to anyone interested in reading this little book that our contemporary world is peopled with folk who can seem pretty homogeneous, apparently mass-produced. Unsurprisingly, it is the rarer, eccentric personalities that typically we remember longest, not only because they stand out, but because they more often make us think a new thought. I was reflecting on this social reality one day nearly sixty years ago with Bernie Campbell, a neighbor and former schoolmate, as we were driving the hilly, dusty backroads of Lanark County, Ontario. “Well,” Bernie said, “folks in the city have things we might wish we had. And they sure are stylish. But I ken what you say–a whole lot of them are too much like each other. What we have for neighbors out here is–well–more interesting. We have way more folks who are just themselves and nobody else.” He pointed to a farm we were passing. “We sold a couple of heifers to that lad once….” He launched into an exceptionally vivid recollection of a haggling session, concluding by saying, “Now that old lad, Davy-boy, was a real character.”

That phrase, commonly used in our part of the world, may refer not only to an eccentric, but also to any person you wouldn’t be likely to confuse with somebody else. I have chosen it as the title of this little book because it typically signifies a more or less consistently ‘real’ person, not a personage (or persona), one who acts and speaks pretty much exactly the same in public as in private. In a culture like that of the upper Ottawa Valley, in which stories about interesting people, living or dead, are a cherished form of entertainment around the stove in winter or the front porch in summer, there are many, many such “real character” stories. They form our oral history, and, though it might seem an irony, the telling of such stories about people who stand out from the herd in one way or another strengthens common identity among neighbors. We are–or used to be–a people who cherish its odd-balls.

The Ottawa Valley is not, properly speaking a ‘character’ in this book, but sixty years ago it certainly had a distinctive character, and some of that still remains. Immigrant origin over nearly two centuries accounts for distinctive accents and tell-tale place names. From Hawkesbury seventy miles below Ottawa to Mattawa (both Algonquin names) more than one hundred miles north of it, settlement history came in three phases. The English came first, often from Yorkshire, yielding names such as By-town (Ottawa’s original name), Hull, across the river, Greely, Richmond and the like. These are in the areas closest to Ottawa and were the first to be parceled out by agents of the Crown to settlers. Next came the Scots, mostly during the late 1700s through the first quarter of the next century, establishing to the south-east the counties of Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry, then the counties of Lanark and Renfrew to the west and north-west. My mother’s family and that of most of their kin came from the first area, my father’s from the second, and I grew up in that area, which extends through good farmland many miles from places like Kinburn, Arnprior, and Braeside until it bumps up against rough rock ridges and irregular hills of the Lanark Highlands near Burnstown, Calabogie, and Renfrew, before edging up and over the hills and following down the Tay River to Perth. By the time the poor Irish and Anglo-Irish came in the 1840s, all that was left was the rough country of Lanark and Renfrew counties. Like everyone else those folks were given a survey map, a bag of flour, a broad axe and other very basic supplies (for which they signed, as often as not with an “X,” being illiterate, unlike their Scottish neighbors) and then set out to clear, in their case, not only trees, but also rocks and boulders from their land. It was tough going. Such was the part of Lanark in which my father sought to establish his ranch. The land was rugged, and its people, both Scottish and Irish, like unto it. We long had a distinctive accent, a blend of Scottish and Anglo-Irish, which has attracted the interest of linguists. We preserved songs and fiddle tunes from the “auld sod” that made our cèilidhs and fairs as distinct from those near Ottawa as our tell-tale accent.

Though I propose to pay tribute in these pages to characters I met in other parts of the world—the United States, England and Italy as well—some of my own favorite “real characters” remain those I came to know when I was younger. Thus, my readers will note that a good many of the persons featured here are from the rural Ottawa Valley, a few from places a good way removed from it, but I think of them all as, in one way or another, “real characters.” Each has an abiding place in my grateful memory because in some distinctive way that person challenged me, taught me, and helped keep my affectations in check. This does not necessarily mean, of course, that all were paragons of virtue.

Among country people there is a strong tendency to identify particular persons with what I like to call a “signature narrative.” The concept is simple, but let me give a brief example.

One day I was walking through one of his back hayfields with Geordy Ellis, himself most definitely a “real character.” We came to a stone fence, beyond which were substantial trees growing up in what apparently had once been meadows. There was a broken line of split cedar fence, disappearing ghost-like into the woods. Geordy saw me looking and said, “This stone one here is my line fence. That on the other side belonged to Jack Logan. It’s long gone back to the Crown now, for taxes.”

“Who was Jack Logan?” I asked, not having heard of him.

“One of the first here,” said Geordy, “neighbor to my grandfather. No family.”

He paused. “Let me tell you about Jack Logan. He was once called to be witness in the court at Almonte. It was a turkey thief had been caught. Judge said, ‘Jack Logan, would you say that man over there was a turkey-stealer?’ Jack thought a minute, then replied, ‘Now Judge, you know I would not like to say such a thing of any man.’ And then, after a long pause: ‘On the other hand… if I was a turkey, and that lad was around, I’d roost me real high.’”

This brief story about Jack, still being told more than three generations after his death, when his cabin and barn had long become useless and his entire farm completely taken back by the forest, remembered him for certain virtues. Apparently the stolen turkeys were in fact his own, but there was in him no thirst for revenge; he managed to bear witness to an obligated truth without risking false witness. His tact and prudential wisdom is still, after all these years, offering counsel to those with ears to hear, not least by means of a good laugh. There are other stories about Jack Logan, but that one persists in community memory because it captures the character of the man, hence bears his ‘signature’—even though he was himself illiterate.

I want as much as possible to bear witness, by means of what seem to me to be signature narratives, to people it has been my privilege to know personally, unlike Jack Logan, who I know only through Geordy’s story.

Often those who tell such stories are as much a story as the one of whom they speak. That would certainly be true of Geordy Ellis. His six-hundred acre cattle farm, along the east shore of White Lake and his famous and beautiful sugar bush, a magnificent stand of maples right by the road, earned him a meager living even after the one-room Uneeda school across the road had been closed, and the students bussed away to the village of White Lake, dispossessing Mrs. Ellis of a job. (Uneeda, by the way, got its name from the whimsy of a late nineteenth-century bureaucrat in some provincial department, who used a formula to determine where rural post offices should be located. He had written ‘uneeda po here’ on his map. There never had been more than the school, Geordy’s cabin, and the larger log house of his brother a mile up the Bellamy Road, so the post office was fiction while the name remained—tenuously—a fact.) Geordy lived with his former schoolteacher wife, son, and daughter in their small log house–just a cabin, really–with only one large downstairs room with a cookstove, table, chairs, and curtains to draw around the bed. There was a small loft above for “the next generation.” No indoor plumbing. Geordy had plenty enough money to build a bigger house. But he wouldn’t. “Those townies,” he once said to me, “spend money like water. This is all you really need,” he said with a sweep of his arm at the old schoolhouse and his own cabin. “All you need, eh?” he repeated, with a laugh.

Geordy’s brother Bill likewise had two children, a boy and a girl. The girl, Alice, had black hair, very white skin, and the biggest freckles I have ever seen. As soon as she graduated from high school she went off to get training as a nurse and never came back. The boy, who was named Elmer, didn’t get past the first couple of grades in elementary school because he was ‘mental,’ as the family put it, probably a victim of Down’s syndrome or something like it. To keep him occupied, his father widened the peg hole on a big square barn timber (roughly 16 inches each side) about 12 feet long and ran a logging chain through it so Elmer could drag it up and down in front of the house. This pleased Elmer enormously, and over time he developed preternatural strength doing it. He had massive arms, hands, neck, and shoulders. Neighbors would marvel at his log-dragging, as it was called, but when he came to town with his father, to whom he was completely obedient, people greeted him affectionately. His favorite treat was a Dairy Queen cone, and that’s where Arnprior folks would often encounter Bill and Elmer Ellis. Elmer spoke few words other than “g’day” or “thank you” and the like, but he smiled a lot and seemed content.

My father and I had firsthand experience of his strength. One day we were coming out the top of our lane in the old Fargo 2 ½ ton flat-bed we kept for hauling hay and feed. The Penishula Road, which runs off the Bellamy and out and down toward Pickerel Bay, is a bit blind just past the ranch lane because of the steep hill on the left, and what with the roar of our old Fargo Dad didn’t hear the school bus coming, and we barely missed a crack-up by swinging hard right. Unfortunately, though the bus passed safely by, one set of our dual wheels was left in mid air over the ditch next to the culvert. Accordingly, we couldn’t get traction to go either forward or back. Several minutes passed, and I was just about to walk the mile back and get the tractor and a chain when a faded blue Ford pick-up appeared.

“Trouble?” asked Bill Ellis. Dad explained. Bill got out of his truck and said simply, “Elmer can fix this.”

He called Elmer over and showed him how we were hung up. Elmer grinned at us and said nothing, but got in the ditch, went into a kind of sumo-wrestler crouch with his hands under the back of the flat-bed and with a great grunt heaved it up on the road far enough that we had traction. I gasped something or other. Dad said, “that lad of your is some strong, Bill,” and Elmer replied with a grin. We thanked them and they were off.

You don’t forget a neighbor like that. Sadly, after his parents at last got to be frail and were worried that he might do harm, Elmer ended up in a provincial facility for the mentally challenged. It so happened that by the time he reached his late twenties he would occasionally speak to a woman, saying, “Nice lady,” and try to pat her arm. Then he took to wandering–sometimes gone for two days. Once he showed up at our back door when neither Dad nor any of my brothers were around, and just stood out there saying “Nice lady.” My mother was terrified, and locked herself in till Dad returned. By this time Elmer had wandered homeward, and Dad met him coming down the lane; he offered Elmer a ride home, and it was accepted. When Elmer was finally institutionalized, even though most neighbors could see it was probably necessary, the community was conflicted. “You have to see the sense in it,” said Donald McNabb, “but all the same you hate to see it come to this.” He spoke for many—though not my mother.

It is worth noting the circumstances leading to Elmer’s being unable to live at home with his frail and aging parents: namely, the alarming reality of his strength as a danger, now, sixty-five years later, is not often retold, but the story of “how Elmer lifted Lyle Jeffrey’s big Fargo truck out of the ditch with his bare hands” is one that remains; it has become his “signature” narrative, and many people besides members of my family tell it. Elmer may well—if oral history is not entirely extinguished by modern entertainments—be remembered as long as Jack Logan.

The persons you will meet in these pages include a cast of old neighbors, Ottawa Valley farmers, ranchers, a rodeo ringer, and other such folk, also a crazy nun, an English poet, and a wonderful auto mechanic. Each of them is one of the people I have come over time to appreciate as “real,” people for whom personal self and public self were largely identical, yet who marched to the beat of a different drummer than many of the rest of us. I am grateful to them all. None is a paragon of virtue; none is a paragon of vice. If you enjoy some of these folks half as much as I do still, then writing these narratives down will have been worth it.

“We have way more folks who are just themselves and nobody else.”

The key word here is “we”. Within a community, you tolerate differences, even quite large ones. Outside of your community, difference or similarity doesn’t much matter, you’re an outsider and that’s that.

The fact is that “we” as Americans don’t view ourselves as a community anymore. It’s delusional to pretend otherwise. Something shattered starting a couple decades ago. One can think it’s coincidental that that’s when the internet arose, but I don’t think that’s tenable.

Agreed, Brian. It would be tough to write that off as a coincidence. Interestingly, reading this immediately made me think of a couple rally good “character” I could tell, from where I live. Then I thought, no, I’m not just going to put one of those stories up in a comment box on the internet, even here at FPR. Stories like that are better than the internet. You should at least have to buy a book, and in person is even better.

Comments are closed.