Lexington, VA. In a late essay, Donald Hall claims that he “practiced an enthusiastic morbidity for decades.”[1] While his work ranges widely, death stretches like a Fate’s thread across it, from his debut poetry collection in 1955 through his final essay collection in 2018. “Open a book of his poems or essays at random and plop down a finger,” John O’Connor notes, “and chances are you’ll land on some combination of death, grief, interment, loss, and the humiliation of aging—in other words, the long, haunting slide into the grave.”[2] Annika Neklason explains that Hall “detailed, again and again, old age and death.”[3] While Hall frequently meditated on his own death, though, much of his best writing commemorates and mourns lost loved ones—especially his maternal grandparents Kate and Wesley Wells and his wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon.

Indeed, Hall is one of American literature’s greatest elegiac poets. In a 2006 interview, Marcia Day Childress asked Hall about “the relationship between poetry and loss and suffering.”[2] He responded, “Poetry typically deals with intense feeling. Suffering and loss—suffering leading to loss—are the most intense of human feelings. Many great poems in the English language are elegiac, dealing especially with the ultimate loss of death.”[3] Hall’s own elegies deeply probe pain and loss. He words them to the extent that they can be worded. He honors the loss of singular people and things. Still, Hall’s grandparents and Kenyon also showed him the limits of an elegiac sensibility, which can lead to self-enclosed despair, to a crippling sense of irrevocable loss. They showed him, for a few happy years, the possibilities of continuity and renewal, of unexpected rebirth.

Death is already at the fore in Hall’s first collection, Exiles and Marriages. “My Son My Executioner” (originally titled “Epigenethlion: First Child”) remains one of Hall’s best-known poems. It explores Hall’s contradictory feelings about the birth of his son. On the one hand, the child promises the possibility of “immortality,” of posterity stretching into the future.[4] On the other hand, the child reminds Hall and his first wife Kirby of their “bodily decay.”[5] Hence the somewhat hyperbolic title and first line. It is a precise, well-crafted poem. Yet it also tilts toward the melodramatic confessionalism that would soon dominate mid-century poetry.

Another poem in the collection, “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” offers a better introduction to Hall’s elegiac concerns. This poem mourns the death of Hall’s beloved grandfather, a New Hampshire farmer with whom Hall spent his boyhood summers. Wells died while Hall was at Oxford, and the poem is a sort of incantation meant to bridge the distance. Hall hopes his words will ride the wind that crosses the Atlantic to rage “Against the clapboards and the windowpanes” of the farm that “lies hard against the foot / Of Ragged Mountain, underneath Kearsarge.”[6] Grief courses through the blank verse lines like that raging wind. Exiles and Marriages was considered for the Pulitzer Prize, but the collection in general and this poem in particular seemed to embarrass Hall in his later years. He included “My Son My Executioner” in his final selected poems but not “An Elegy for Wesley Wells.” Hall told Allan Cooper in a late interview that he was never fully pleased with the poem, “that it strained to become, oh, ‘Lycidas’ maybe.”[7] Nevertheless, it is a powerful elegy, and its concerns echo in Hall’s later writings.

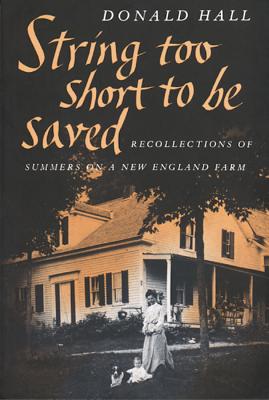

This is certainly true of the 1961 prose work, String Too Short to Be Saved, which traces Hall’s elegiac sensibility back to those summers with Wesley and Kate Wells. Hall grew up in suburban Connecticut. An elite trajectory took him from Phillips Exeter Academy to Harvard to Oxford to Stanford and then back to Harvard again as a fellow. But the ancestral farm at Eagle Pond remained his spiritual home. String Too Short to Be Saved shares Hall’s memories of working alongside his grandparents at the farm: gathering eggs, milking cows in the tie-up, haying the fields. These rural tasks gave him a sense of usefulness, skill, accomplishment. (The rhythms and satisfactions of work are another of Hall’s central themes, as evidenced by his poem-turned-children’s book Ox-Cart Man and his 1993 nonfiction volume Life Work.) These tasks also gave Hall a sense of belonging. The shared work deepened Hall’s bonds with Kate and Wesley, with the surrounding community, with the fields and forests of rural New Hampshire.

Throughout the memoir, this elderly couple attempts to pass on the past. Wesley, kindhearted but mischievous, always has a story to tell. String Too Short to Be Saved recounts a number of these stories, including a humorous “who done it?” in which Wesley tracks down a sheep thief who wears two left boots. Hall’s grandmother Kate maintains a shrine-like “gallery of pictures” in the sitting room and parlor at Eagle Pond: “Daguerreotypes, tinted photographs, yearbook groups in cap and gown, blurred Brownie snapshots, field-hockey teams, wedding portraits, silhouettes, pictures taken when the subject knew he was dying, Automatic Tak-Ur-Own-Pix, and the crayon drawings you can commission at county fairs for a dollar.”[8] Hall meditated on these pictures during his visits: “Most of the faces belonged to men and women who had died before I was born, but I memorized their names, and my grandfather’s stories which gave life to the names.”[9]

Undoubtedly, the stories, pictures, and experiences at Eagle Pond shaped Hall’s elegiac sensibility. Still, he claims there was nothing elegiac about his grandfather’s storytelling. Wesley’s stories seemed to bring the past into the present for him, to bridge time. It was the youthful Hall who gave them an elegiac cast. In Hall’s first few summers at the farm, it seemed like the familiar pattern would carry on forever, but as he grew older—and as his grandparents’ friends and relatives began to die—he became acutely aware that Kate and Wesley were approaching death too.

In the opening pages of String Too Short to Be Saved, Hall and his grandfather attempt to round up some heifers that have broken out of their fence and gone half-feral in the surrounding woods. Hall was an excellent comic writer, and this is the premise of a comic tale, but both real and figurative storm clouds loom over their unsuccessful quest. Hall must soon leave New Hampshire for the school year, and he continually fears that his grandfather—who easily loses his breath these days—is overexerting himself. Will this be their final summer together? A thunderstorm leads them to seek shelter in the crumbling house of Ned Masters, an old friend of Wesley’s. Ned has recently been in the hospital, and his deteriorating health matches his deteriorating abode: “The chimney curved like the chimney of a very wicked witch, and grass grew out of the roof around its base.”[10] Ned’s complaints about aging clearly distress Wesley. Hall realizes that his grandfather does not want him to hear these complaints. He wants to shield his grandson from the prospect of death. Wesley does not realize how much his and Kate’s deaths already weigh on his grandson’s mind. In a sense, Hall already mourns their death as thunder rumbles outside the crumbling house.

In String Too Short to Be Saved, Hall’s elegiac portrait of his grandparents extends to the rural world in which they live. He sees signs of decline everywhere, in the cellar holes that mark long-abandoned farmsteads in the regrown woods, in the crooked chimney and grassy roof of Ned Masters’ house, in the ivy that consumes his uncle Luther’s cottage. Already, in his youth, Hall had decided that Wesley and Kate were living out a way of life that would disappear with them. In “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” Hall calls him “the noble man in the sick place.”[11] In those summers at Eagle Pond, Hall decided “that to be forgotten must be the worst fate of all.”[12] String Too Short to Be Saved —along with much of Hall’s prose and poetry—is a passionate attempt to make sure that the people and places he loved are not forgotten, to pass the stories and images of Eagle Pond on to others, to transfer Kate Wells’ gallery on to as many bookshelves and into as many libraries as possible.

Hall writes elegiacally of the people of rural New Hampshire, but he also writes elegiacally of places and things. Returning once more to “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” Hall describes how New Hampshire farmhouses’ “Georgian firmness sagged, and the paint chipped, / And the white houses rotted to the ground.”[13] In “The Night of the Day,” a poem from Hall’s 1996 collection The Old Life, Hall recounts the story of Peter Butts, who instead of cutting firewood one winter burned all of the things in his attic: “busted / rocking chairs, spinning wheels, pictures frames, / and wooden chests that saved dead people’s / frocks and union suits.”[14] It is almost as if Hall tries to snatch those things from the fire with his poem.

Hall’s elegiac sensibility often verges on despair. At the end of String Too Short to be Saved, he writes: “Yet what was real and has ceased to be real is nothing, and to value nothing is to be sentimental. The reality of the suburbs had allowed me exile in the nostalgic order of the farm. Hatred of living anarchy became love of dead order. Nostalgia was self-hatred. Yet the suburbs were no better, for being real, than they had been before I understood. I saw that I stood nowhere at all.”[15] The sense of irrevocable loss and deracination resurface in Hall’s poem “Mount Kearsarge,” from the 1969 collection The Alligator Bride, in which he remembers standing on the porch of Eagle Pond as a boy, looking at the “Great blue mountain!”[16] It ends with Hall’s lament: “I will not rock on this porch / when I am old.”[17]

But Hall did grow old at the foot of Mount Kearsarge, in Wesley and Kate’s farmhouse at Eagle Pond. In midlife, while teaching at the University of Michigan, Hall and his first wife divorced. He spent half a decade struggling with depression and aimlessness. Hall eventually began to date Jane Kenyon, a former student. They married, and after spending some time visiting Eagle Pond, Kenyon encouraged Hall to leave his professorship so they could move there together. They did so in the mid-70s, inaugurating the happiest period of Hall’s life. (He would publish a 1986 poetry collection unironically titled The Happy Man.) Kenyon was a poet as well, and they developed a daily ritual of writing, caring for the old farm, hiking in the mountains, and swimming in the pond during summer.

These years showed Hall the limits of his elegiac sensibility. Elegy has often been accused of nostalgia, and this can be a danger. Elegy can be idealistic and romantic in the worst senses of the word. Still, knee-jerk or blanket accusations of nostalgia can distort in their own way. Hall certainly wishes to purge his work of any nostalgic indulgences or cheap consolations. Good people and good things are lost all the time. The best elegies, like Hall’s, grow out of the need to recognize this, to honor what is lost by recognizing it as loss. But there is another, less widely noted, danger, especially when we move from individual elegiac works to a broader elegiac sensibility. This sensibility can verge on despair. It can lead to a sort of blindness, a failure to recognize possibility. Hall recognized this when he returned to Eagle Pond. In his epilogue to the republication of String Too Short to Be Saved, Hall writes about how, as much as rural New Hampshire had changed since his youth, he was delighted to discover that it continued to offer a rich communal life. He and Jane joined friends and neighbors in that life. They began to attend South Danbury Church with Hall’s relatives, listening to sermons from the pulpit where his uncle Luther preached during his childhood.

Hall discovered that he had not recognized “the power of place and tradition to re-embody itself.”[18] He continued to write elegies, but the past no longer tasked him with elegy alone. It also gave him the gift of new life from these old roots. This realization is at the heart of Hall’s 1978 collection Kicking the Leaves. In “Maple Syrup,” Hall and Kenyon look for Wesley Wells’ grave in the cemetery. They find the graves of many ancestors—“Keneston, Wells, Fowler, Batchelder, Buck”—but not Wesley’s. [19] Returning home to Eagle Pond, they “explore the back chamber / where everything comes to rest: spinning wheels, / pretty boxes, quilts, / bottles, books, albums of postcards.”[20] Then they go down the cellar steps and discover the last jar of Wesley’s maple syrup, sealed a quarter century before. They take it back to the kitchen and “dip our fingers / in, you and I both, and taste / the sweetness, you for the first time, / the sweetness preserved, of a dead man / in his own kitchen, /giving us / from his lost grave the gift of sweetness.”[21] The sweetness is not only of the syrup but of renewed life, of their life, at Eagle Pond. They have found Wesley in the home, not the graveyard, and he has given them a blessing, a gift of hope. (Interestingly enough, Hall would revise the ending of this poem to make it more elegiac in future versions.)

The title poem of Kicking the Leaves is another of Hall’s meditations on mortality, but here the prospect of death can heighten appreciation of the present moment. It can sharpen one’s awareness of the goodness of life. The leaves—a memento mori—can be kicked. The poem begins with Hall kicking leaves on the way home from an Ann Arbor football game. This stirs a memory of Hall kicking leaves as a child on the way to school, which in turn stirs a memory of buying cider. The first section ends with a memory in which Hall knew “my father would die when the leaves were gone.”[22] Yet in the poem’s final section Hall leaps upon a pile of leaves:

Now I leap and fall, exultant, recovering

from death, on account of death, in accord with the dead,

the smell and taste of leaves again,

and the pleasure, the only long pleasure, of taking a place

in the story of leaves.[23]

Here a consoling—even joyous–prospect of continuity and cycle wards off the specter of death that so often haunts Hall’s works.

Kicking the Leaves also contains an elegy for Kate Wells, who died the same year in which Kenyon and Hall returned to Eagle Pond. While the elegy for Wesley rages against distance and death, the prose poem for Kate is intimate and quiet, narrated from her bedside, which Hall attended. It is stark and unflinching in its own ways: “My grandmother chokes on a spoonful of water and the nurse swats the fly.”[24] Ultimately, though, Hall’s elegy for his grandmother is a far more peaceful poem than his elegy for Wesley. It stresses continuities: “I dream one night that we live here together, four of us, Jane and I with Kate and Wesley.”[25] And the poem suggests that in an important sense they do all live together: “We live in the house left behind; we sleep in the bed where they whispered together at night.”[26]

There are meditations on mortality throughout Hall’s poems, but what of intimations of immortality? These are much fewer and often ambiguous. They trail off in his later writings. (Hall’s late essay on “Death” is resolutely about mortality.) When Hall and Kenyon first returned to Eagle Pond, though, he notes how they “lived in the constant presence of the dead that autumn. In the barn someone called Jane by name. At South Danbury Church I saw my great grandfather alert in the pew beside me, and I watched my grandmother’s black sequined hat bobbing over the organ she had played for seventy-six years, from the age of sixteen to ninety-two.”[27] Hall and Kenyon first attended church for community (and out of worry that Hall’s relatives would expect them to be there). But a Rilke-quoting minister soon had them reading theologians and mystics. This is evident in Kenyon’s poetry, with its direct explorations of faith and doubt. Religious themes are more muted in Hall’s poetry. In “Stone Walls,” though, the final poem in Kicking the Leaves, he writes,

At Church we eat squares of bread, we commune with mothers

and cousins, with mothering-fathering hills, with dead and living,

and go home in gray November, in Advent waiting,

among generations unborn

who will look at the same hills, as the leaves fall and turn gray,

and watch stone walls ascending Ragged Mountain.[28]

Yet from there the poem moves on to an imagined post-apocalyptic future, in which “gangs fight with dogs for the moose’s body,” and where continuity comes only from the stone faces of now-nameless mountains that still “emerge from leaves in November.”[29]

Hall and Kenyon had two happy decades together at Eagle Pond. They were grateful for it and poignantly aware of its fragility. Kenyon’s poem “Otherwise,” for instance, records a cherished daily routine—eating breakfast, walking the dog, working on poetry, lying down with Hall at noon, eating dinner with him “at a table with silver / candlesticks.”[30] Kenyon reminds herself four times throughout the poem, though, that “It might / have been otherwise.”[31] Each time the enjambment offers a hint of apprehension. The poem ends, “I slept in a bed / in a room with paintings / on the walls, and / planned another day / just like this day. /But one day, I know, / it will be otherwise.”[32]

Since Hall was much older, they both assumed that he would die first—especially when he was diagnosed with cancer. (See Kenyon’s strange, powerful poem “Pharaoh.”) But shortly after Hall recovered, Kenyon was diagnosed with leukemia. She would die in 1995, at the age of forty-seven, with Hall beside her. Hall helped prepare her volume of selected poems during her illness. It was published posthumously, under the title Otherwise. Hall poured his grief into his writing, as if all his earlier elegiac poems were preparation for the great, terrible task of mourning Kenyon. Hall’s 1998 collection Without and his 2002 collection The Painted Bed collect these poems of mourning. They range from the mordantly humorous and the savagely raw to the delicate and touching. “Summer Kitchen” is one of several poems that could serve as a companion to Kenyon’s “Otherwise.” In it, Hall recalls watching her crushing “garlic in late sunshine,” preparing a sauce for dinner.[33] She tells him to light a candle (presumably in the candlesticks mentioned in her own poem), and it ends with the lines: “We ate, and talked, and went to bed, / And slept. It was a miracle.”[34] In 2005 Hall published the acclaimed memoir The Best Day the Worst Day: Life with Jane Kenyon, and one of his final essays continued the work of mourning. It ends, “In the months and years after her death Jane’s voice and mine rose as one, spiraling together images and diphthongs of the dead who were once the living, our necropoetics of grief and love in the unforgiveable absence of flesh.”[35]

In his final years Hall set aside poetry, but he continued to write essays, many of them about aging and the prospect of death. In the aptly named “Death,” Hall heaps scorn on our tendency to use euphemisms, both religious (“return to the Lord”) and secular (“pass away”), to avoid saying the word itself.[36] After surveying different methods of burial, he proclaims, “Myself, I’ll be a molderer, like my wife Jane.”[37] Hall decries how nursing homes have become “storage bins [that] bear encouraging names.”[38] Despair is not far from the surface of the essay, despite its hardboiled stance. It perhaps comes closest to surfacing when Hall proclaims that he will be the last of his family to live at Eagle Pond: “My kids and grandkids don’t want to live in rural isolation—why should they?—but it’s melancholy to think of the house emptied out. Better it should burn down.”[39]

Hall offers no pat solace for the loss of loved ones and loved places. He carried on the task of mourning throughout most of his life. He knew that untold numbers of people mourn lost loved ones for decades in loneliness. His poetry gives fitting words to such loneliness while also insisting that no words are truly fitting. He likewise knew that thousands of farms across New England and beyond were vacant or deteriorating, the once-cherished heirlooms in their backrooms and attics destined for a dumpster or an antique booth. He figured Eagle Pond would join them, and he gave words to this pain too. But after his death the farm was purchased by preservationists. Friends bought some of his cherished possessions at auction so that the house would not be emptied out. His books preserved Eagle Pond on the page. They also helped preserve it, at least for a time, in real life. And perhaps this fragile continuity allows us to turn back to those happy decades at Eagle Pond when Hall could kick the leaves in peace. Hall’s elegiac poetry and prose teach grim lessons that are worth heeding, but there is also a sort of unsentimental, necessary hope—a hope for continuity and unexpected rebirth, a hope that keeps open a sense of possibility—that shines obscurely beneath their grief. In this way Hall’s works can teach us both elegy’s lessons and its limits.

- Donald Hall, “Death,” in Essays After Eighty (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 93. ↑

- John O’Connor, “An Interview with Donald Hall,” The Believer, May 1, 2018, https://believermag.com/an-interview-with-donald-hall/. ↑

- Annika Neklason, “What Donald Hall Understood About Death,” The Atlantic, June 26, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/06/what-donald-hall-understood-about-death/563768/. ↑

- Hall, “Epigenethlion: First Child,” in Exiles and Marriages (New York: The Viking Press, 1955), 106. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Hall, “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” in Exiles and Marriages, 96. ↑

- Allan Cooper, “Three Questions for Donald Hall,” Numéro Cinq 8, no. 1 (2017). http://numerocinqmagazine.com/2017/01/08/three-questions-donald-hall-interview-allan-cooper/ ↑

- Hall, String Too Short to Be Saved (Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1980), 37-38. ↑

- Ibid., 37. ↑

- Ibid., 18. ↑

- Hall, “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” 98. ↑

- Hall, String Too Short to Be Saved, 38. ↑

- Hall, “An Elegy for Wesley Wells,” 98. ↑

- Hall, “The Night of the Day,” in The Old Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996), 9. ↑

- Hall, String Too Short to Be Saved, 275. ↑

- Hall, “Mount Kearsarge,” in The Alligator Bride: Poems New and Selected (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1969), 89. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Hall, “Epilogue: More String” in String Too Short to Be Saved, 288. ↑

- Hall, “Maple Syrup,” in Kicking the Leaves (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1978), 25. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid., 27. ↑

- Hall, “Kicking the Leaves,” in Kicking the Leaves, 28. ↑

- Ibid., 34. ↑

- Hall, “Flies,” in Kicking the Leaves, 38. ↑

- Ibid., 41. ↑

- Ibid., 42. ↑

- Hall, “Epilogue,” 287. ↑

- Hall, “Stone Walls,” in Kicking the Leaves, 58. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jane Kenyon, “Otherwise,” in Otherwise: New and Selected Poems (Saint Paul: Graywolf Press, 1996), 214. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Hall, “Summer Kitchen,” in The Painted Bed (Boston: A Mariner Book, 2003), 45. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Hall, “Necropoetics,” in A Carnival of Losses: Notes Nearing Ninety (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018), 146. ↑

- Hall, “Death,” 89. ↑

- Ibid., 90. ↑

- Ibid., 97. ↑

- Ibid., 91. ↑

Thanks for this, Steven. I haven’t read much of Hall’s poetry yet, but I read String Too Short to Be Saved a few months back and really liked it. And I’m planning to read Christmas at Eagle Pond over my holiday break.

Thanks for the note. I hope you enjoy Christmas at Eagle Pond!

I appreciate your reminding readers that possibility is the energy that drives even tragic or elegaic poetry. Homer and Vergil to Eliot and Hall.

Comments are closed.