Boise, ID. I have written before about the pleasures I find in re-reading particular books every year. I have designed a liturgical calendar of reading that leads me through particularly rich and meaningful novels at set times of the year. Like the church calendar, my liturgical year begins with Advent. As December closes, I have just finished re-reading The Lord of the Rings: my Christmas gift to myself. Tolkien’s work is fitted to the rhythm of Advent with its long-deferred hopes, its Eucatastrophic climax, and its festal conclusion of births and plantings and strawberries. The destruction of the one ring and the crowning of Aragorn fit emotionally and aesthetically into the new hope of Christmas. By the twelfth day of Christmas I have been born anew into the work of Creation.

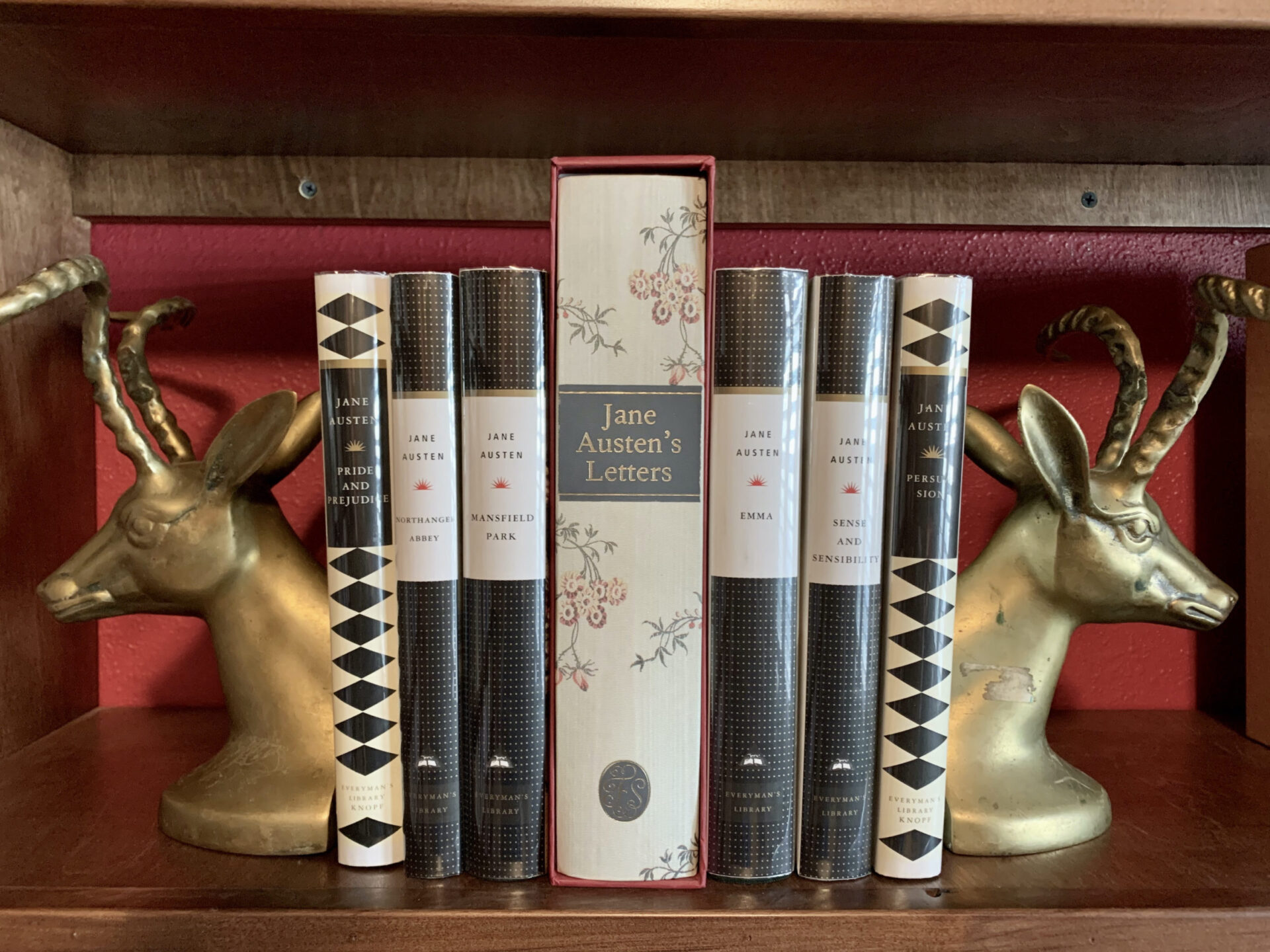

With the opening of the New Year I move to the Epiphany stage of my reading year and re-read Jane Austen’s six novels. Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion are each delightful and instructive in their own way. Pride and Prejudice is possibly my favorite, although that preference can be changed by mood or moral need. Reading at the pace of a book a week (although Emma may take a bit more and Northanger Abbey a bit less) carries me into February. To start one of the novels on a Sunday afternoon, and finish it on a Friday evening carries me through the darker weeks of winter in thoughtful comfort: the comfort of familiarity and of challenge.

When I first began to develop this habit of set cyclical re-readings I was primarily motivated by the desire for a discipline of reading to give structure to my gluttonous habit of reading and re-reading books in huge quantities and according to my immediate desires. It was sometime in the middle of an autumn and I had just finished reading Pride and Prejudice for the third time in a few months and I hadn’t enjoyed it very much. I had raced through the intermediate tension of Lydia’s elopement wanting the gratification of Darcy’s declaration “I believe I thought only of you.” And, as is the fruit of vice, the pleasure I sought had vanished.

Jane Austen is, more than Plato, more than Aristotle, more than Alisdair MacIntyre, the philosopher of virtue. In each of her novels, the plot turns on the practice of virtue by complex, ordinary, and very real human characters. Thus, she is the author to read as you embark on the new year. Living in the immanence of Christ’s birth, we not-yet-sanctified people crave a community of virtue. Austen is often considered a “marriage-plot” author; however, her marriage plots are but clever disguises for virtue-plots.

The protagonists of her stories are the virtues, and the antagonists the vices. Pride and Prejudice are conniving to destroy Humility and Wisdom: Elizabeth and Darcy are the battleground on which the epic battle is fought. Greed and Selfishness wage a war of attrition against Generosity and Compassion in Sense and Sensibility and are only just beaten in the last battle as Marianne recovers from her fever. Fortitude wins a glorious contest against Envy, Sloth, and Lust in Persuasion. Humility is victorious and happy over the shame and guilt and misery of Pride in Mansfield Park. Further, these large battles are then the background of a myriad of small adventures: vice and virtue skirmishing in small conversations, subtle interactions, mere descriptions. Lady Catherine de Bourgh declares, “If you are speaking of music . . . it is of all subjects my delight. There are few people in England I suppose, who have more true enjoyment of music than myself, or a better natural taste. If I had ever learnt, I should have been a great proficient.” And Vanity is victorious for the moment. Cynicism ventures against sincerity when Elizabeth says: “One cannot be always laughing at a man without now and then stumbling on something witty.” And Sloth is corrected when she declares that “The distance is nothing when one has motive.”

The enduring value of adding Jane Austen to my disciplines was not beholden to my expectation of enjoyment from a happy wedding nor was it dependent on my recognition that vice and virtue are at war in me and in the world. She won me by shaping a vision of joy built on virtue and a corresponding vision—gently elided in her prose—of the despair of vice.

Banner photo courtesy of Amanda Patchin. Jane Austen portrait by Cassandra Austen.

I too love re reading books, and reread Jane Austen quite often. The idea of a reading calendar akin to a liturgical one is awesome. Any further suggestions through the months?

I don’t have a full calendar developed, but I do read Tolkien in December and often revisit favorite philosophical works over the summer (they prompt long conversations during summer hikes or over beers on the porch). Spring time is when I give my desire for new books free rein and Fall when I re-read simple and comforting books like C.S. Lewis’s devotional works and Ursula Le Guin’s fiction.

Comments are closed.