Atlanta, GA. It’s been a rough few years for celebrity evangelicals. In the summer of 2019, Joshua Harris—the Calvinist pastor who became a national sensation in the late ‘90s with the publication of his book I Kissed Dating Goodbye—announced that he was splitting up both with his wife and with Christianity. “I have undergone a massive shift in regard to my faith in Jesus,” he wrote on Instagram. “The popular phrase for this is ‘deconstruction,’ the biblical phrase is ‘falling away.’ By all the measurements that I have for defining a Christian, I am not a Christian.” Just a few weeks later, the Hillsong worship leader Marty Sampson said on the same website that he is “genuinely losing my faith, and it doesn’t bother me. [ . . . ] All I know is what’s true to me right now, and Christianity just seems to me like another religion at this point.” (He has since deleted the post and denied that he’s left Christianity altogether.) More recently, Carl Lentz, the pastor of the celebrity-friendly Hillsong Church and a celebrity in his own right, was removed from his position because of sexual impropriety. The details of his lifetime came out in a New York Times piece by Ruth Graham: he tended to avoid (non-famous) congregants on Sunday mornings, and celebrities were given special preferred seating during services.

There’s been no shortage of responses to these events from Christian media, and those responses have rather predictably run the gamut from banal to insightful. One of the best essays came from First Things’s Carl Trueman, who helpfully noted the medium of Joshua Harris’s message:

[T]he style of his apostasy announcement is oddly consistent with the evangelical Christianity he used to represent. He revealed he was leaving the faith with a social media post, which included a mood photograph of himself contemplating a beautiful lake. The earlier announcement of his divorce used the typical postmodern jargon of “journey” and “story.” And both posts were designed to play to the emotions rather than the mind. Life, it would seem, continues as performance art.

Trueman’s attack is on the Young, Restless, and Reformed movement that Harris represented at the height of his visibility; he says that such movements often operate based on a “kind of messianic self-consciousness” that ignores or rationalizes “the evidence that we are corrupt, or employ seriously corrupt people.” Matthew Tingblad fills in the gaps in Trueman’s analysis by focusing on the masses who follow people like Harris and Sampson rather than on the institutions that support them. “We have attached ourselves to big-name Christian ‘celebrities,’” he writes on his blog, “idealizing them inside our heads, and the church has oriented herself around these figures.” Young, Restless, and Reformed and Hillsong rose and fell not based on the soundness of their doctrine but on the charisma of their leaders, their ability to work within the model of celebrity that our culture specializes in.

The Culture of Narcissism

An infamous Time Magazine article from 2013 presented a series of unpleasant facts about millennials. Millennials like me—I was born in 1982, eight years after Harris, three after Sampson, and two after Lentz—are used to breathless articles telling us that we’re the worst generation in American history, that we’re self-obsessed and entitled. But this article puts all the studies together into a particularly bleak picture:

The incidence of narcissistic personality disorder is nearly three times as high for people in their 20s as for the generation that’s now 65 or older, according to the National Institutes of Health; 58% more college students scored higher on a narcissism scale in 2009 than in 1982. Millennials got so many participation trophies growing up that a recent study showed that 40% believe that they should be promoted every two years, regardless of performance. They are fame-obsessed: three times as many middle school girls want to grow up to be a personal assistant to a famous person as want to be a Senator, according to a 2007 survey; four times as many would pick the assistant job over CEO of a major company. (Stein, par. 2)

Millennials have had to learn to be skeptical about studies pegging them as narcissistic, just because there have been so many of them and they have so often been used to tell them that they are what’s wrong with the world. But the data that says my generation is obsessed with fame rings true to me, if only because of my personal experience. The desire to be famous—to be known, to be respected—poisons nearly everything I do.

How to Be a Saint

I will take it for granted that the goal of human life is sainthood—sanctification, becoming like Christ and free from our sins. We might also describe this process as the development of virtue, a term that designates the sorts of qualities that mark a good person by the standards of the society or group making the evaluation (Aristotle would frame the human good in these terms). A list of virtues is, in effect, a description of a good person. St. Paul rather famously provides such a list in Galatians 5:22-23: “By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control” (NRSV). One way of thinking of these qualities is as a description of the character of Jesus Christ; and since the goal of Christian life is to become like Christ, these are the qualities that make a person good or holy, or, if you prefer, the qualities that allow a person to be what he is supposed to be from a Christian perspective. We can therefore evaluate our actions by their “fruit”—does doing this or that make me (however slowly) more loving, joyful, etc.? If so, it’s a virtuous action. But if it tends to instill the opposite qualities, if it promotes the vices listed a few verses earlier (“fornication, impurity, licentiousness, jealousy, anger, quarrels, dissensions, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like these”), an action is vicious.

This is not the only virtue system, however: Every group has one, implicitly or explicitly, and in some cases there are striking differences among them. What is a virtue in some communities might be a vice in others. For example, because Christians take pride to be a particularly malignant vice, humility has taken on an important role among the Christian virtues. But humility was a vice for the ancient Athenians. A humble person, Aristotle says in the Nicomachean Ethics, “being worthy of good things, robs himself of what he deserves, and to have something bad about him from the fact that he does not think himself worthy of good things, and seems also not to know himself; else he would have desired the things he was worthy of, since these were good” (4.3). Aristotle would be confused by what we say before the Eucharist each week: “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.” And he’d be horrified by St. Paul’s admonition to “regard others as better than yourselves” (Philippians 2:3). Appropriate self-regard is at the heart of his understanding of human goodness.

Other times, competing virtue systems will use the same term but understand radically different things by it. In his book After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre gives the example of chastity. The Catholic Catechism prescribes chastity for everyone; for the unmarried, of course, it means celibacy, but married people are also called to chastity. For them, it means avoiding “The deliberate use of the sexual faculty, for whatever reason, [ . . . ] outside of ‘the sexual relationship which is demanded by the moral order and in which the total meaning of mutual self-giving and human procreation in the context of true love is achieved’” (§2352)—a remarkably stringent definition that excludes contraception, masturbation, and prostitution, among other things that secular Western culture tends not to see as great evils. Compare this understanding to the rather more lax definition given by Benjamin Franklin in his table of virtues: “Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation” (65). Whatever else we might say about these two definitions, it ought to be clear that a Catholic and a Franklinian can have no conversation about chastity without having a more fundamental conversation about definitions. A chaste Franklinian may well be viciously lustful from the Catholic perspective.

I’ve made this detour into virtue ethics because all human actions presume some system of values and virtues, some ultimate good toward which they aim, the philosophical term for which is telos. The telos of all Christian action is sainthood, and it presupposes a certain set of virtues. As MacIntyre puts it, “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’” In other words, to become a saint means situating ourselves in the story of sainthood, which is not the same thing as the story of celebrity. If sainthood is indeed the goal we should all be aiming at, it will be impossible for us to understand the morality of a particular action if we’ve adopted a false telos and a false story—if we don’t know what we were made for. It’s not impossible to be moral with a false telos, but our morality in such cases is accidental, or we might say parasitic: When I misunderstand human teleology, I can do the right thing only when the virtues of my false telos match up with those of sainthood.

Celebrity is a major telos of contemporary Western society, and I think we’ll understand how radically it departs from the Christian understanding of the good if we examine the virtues it presupposes. I’ve managed to think of a few, though we need not imagine this list to be exhaustive:

- To some degree, excellence in one’s field—though in late capitalism, there are many people whose talent and discipline are largely irrelevant to their celebrity. For a time, in fact, one of the surest paths to celebrity was to make a sex tape and have it “accidentally” leak to the internet. Excellence in one’s field can be a virtue for sainthood, I think, provided it is not pursued for false reasons. Clearly not all fields are created equal in this regard. Excellence as a theologian can clearly aid in the theologian’s own sanctification as well as that of her readers. Excellence as a doctor can direct a person’s attention to the suffering of others and instill compassion. Excellence as an artist can put a person in contact with beauty and help others to see it too. Excellence in athletics can, I suppose, do the same. But the things that make a person famous in this society tend to be the lesser disciplines—and in any case, I suspect that celebrity often makes it harder to be truly excellent, for reasons that I will go into in a moment.

- Self-promotion. It’s exceedingly rare for a person to become famous without directed self-promotion, such that in many cases self-promotion is the person’s actual discipline. It’s easier to become a famous artist by behaving outrageously than by making something good or beautiful or true. It hardly needs to be said that self-promotion is inextricably at cross-purposes from sainthood, with its requirement of humility.

- Conformity to the major virtues of society. To be a celebrity in the twenty-first century is to risk being canceled if one fails to behave by the ethics of society. This is so true, in fact, that one of the surest ways to determine the real, as opposed to the stated, virtues of a given society is to look at the people who achieve fame. Again, we’re at serious cross-purposes with sainthood. Because even the most religious society is, according to the Christian understanding of things, fallen, sainthood always has a prophetic edge; it involves telling people that they need to repent. It’s hard, though I suppose not impossible, to get famous for doing that. (Martin Luther King, Jr., did.)

Not only are the virtues of celebrity not Christian virtues, but they are oftentimes actively opposed to them: If everything we do either brings us closer to sainthood or takes us further away from it, the sources of celebrity draw us away. And that’s not even considering what being famous must do to people. The comedian John Mulaney has a bit about working with Mick Jagger on Saturday Night Live. Jagger was, to understate it, not a nice person:

Mick Jagger would go like this: He’d go, “Diet Coke!” And one would appear in his hand. Now that’s not nice, right? The way I was raised, you’re supposed to say, “May I please have a Diet Coke, please?” And then maybe you will get one. And I bet all of you were taught to say “please” and “thank you.” But if all of us could go, “Diet Coke!” and one would appear in our hand, we’d do it all day long. Even if you don’t like Diet Coke, you’d summon them so you could chuck them at oncoming cars. Famous people are often rude because they’re used to getting things really quickly. I bet a lot of us are pretty polite, but as soon as we get things quickly, we start to get ruder and ruder.

Mulaney frames this as manners, as Jagger violating the social contract, but I suspect it goes deeper than that: Half a century of enormous fame has changed who he is, what he’s capable of. Fame convinces people that they deserve to be feted and celebrated.

Yet the moment we begin to focus on our accomplishments, our own goodness, we turn away from God. This should be apparent from the Beatitudes:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted all the prophets who were before you. (Matthew 5:1-11)

Does celebrity as a goal or an achievement foster any of these things? It encourages us to be rich in spirit and to care about the kingdom of earth and its temporal rewards. The comforts it offers are likewise distinctly human. Its emphasis on self-promotion turns meekness into a vice. It wants us to hunger for validation, not righteousness. I suspect it’s hard to succeed at the highest levels while being pure at heart—and even harder to remain so. It teaches us to avoid persecution, or to seek it from a despised out-group. And whatever falsehoods are spoken against a celebrity generally (though not always) have little to do with Jesus Christ.

Celebrity and Vocation

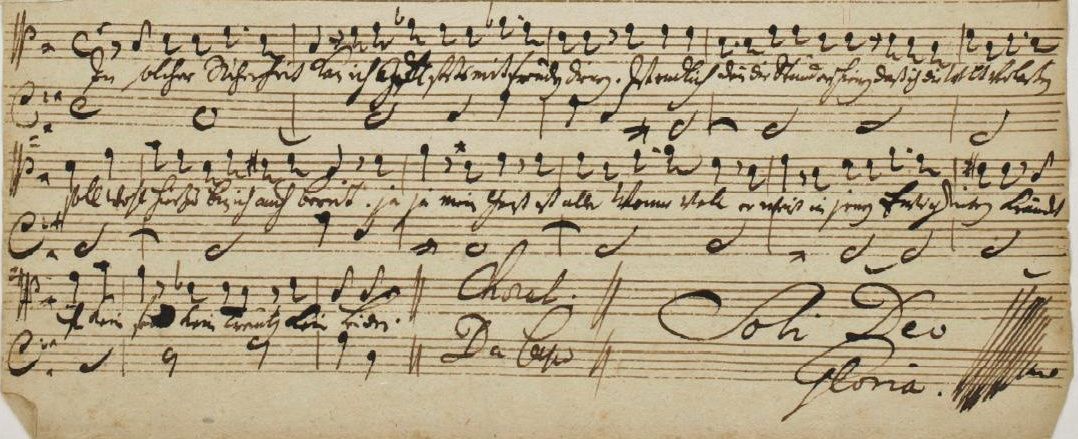

Artists and intellectuals—two groups that I flatter myself as belonging to—are perhaps especially prone to the desire for celebrity. But the problem with celebrity for the artist and the intellectual is that it covertly cannibalizes their mission. Ideally, after all, all workers should be focused on the object of their labor, with the glory of God as a final goal beyond that. To use a frequent example of Plato’s, the telos of a shipbuilder is the ship—a well-built ship by the standards of the practice of shipbuilding. The poet’s telos is the poem; the painter’s is the painting; the intellectual’s is the argument. The Christian worker understands that a well-built object brings glory to the God who gave the gifts that enabled its building, even if the work pays no explicit attention to God. That’s why Johann Sebastian Bach wrote Soli Dei Gloria—“glory to God alone”—at the bottom of his compositions, including his secular compositions. A tertiary telos for human work is the good of its human user: The shipbuilder builds his ship so that people can sail across the Atlantic; the poet and the painter create their art to bring delight and instruction to the people who encounter it; and the intellectual writes her argument to lead her readers toward the truth. But the audience must be a subordinate consideration, because to build a good ship by its very nature is to help people sail. And because art and argument so often go unappreciated at the time they’re made, the artist must focus on creating something good, and the intellectual something true, without regard for the immediate tastes of their audience.

This table of values leaves the craftsman himself entirely aside, subjugated to the object of his labor and to his divine (and eventually his human) audience. Ultimately, as Jacques Maritain argues in Art and Scholasticism, these are the conditions for true art—conditions which have been largely impossible since the dawning of the modern age and the creation of the Romantic artist or author. In the Middle Ages, “the artist had only the rank of artisan,” and he was invisible to himself while he was creating his art:

Matchless epoch, in which an ingenuous people was formed in beauty without even realizing it, just as the perfect religious ought to pray without knowing that he is praying [ . . . ] Man created more beautiful things in those days, and he adored himself less. The blessed humility in which the artist was placed exalted his strength and freedom. The Renaissance was to drive the artist mad, and to make of him the most miserable of men—at the very moment when the world was to become less habitable for him—by revealing to him his own peculiar grandeur, and by letting loose on him the wild beast Beauty which Faith had kept enchanted and led after it, docile. (24-25)

Maritain wrote these words in 1920, near the dizzying apex of High Modernism. The Romantics had turned the artist into a celebrity, with Lord Byron attracting international crowds for his good looks and outrageous behavior as much as for his poetry. The Modernists were in the middle of turning the artist into a god, specifically because of her status as the creator of truth, beauty, and goodness. That process, too, had begun with the Romantics, with Percy Bysshe Shelley’s famous declaration that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World” (701). By the time of James Joyce, the artist had become nearly omnipotent. “This race and this country and this life produced me,” says Stephen Daedalus in Joyce’s autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. “I shall express myself as I am” (147). Joyce’s art thus becomes a form of earth-shattering self-assertion, a new creation of the artist’s world through the artist’s eyes. When T.S. Eliot says, after The Waste Land’s six cantos of cultural dissolution, exhaustion, and despair, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins” (l. 430), he’s getting at something similar, albeit in a more pessimistic register: The meaning of the world has shattered into a billion pieces, and it’s the heroic artist who puts them back together. We’re a long way from the medieval model of the artist as a humble craftsman, a shipbuilder in words or paint.

The Artist and the Market

A century later, we know that artists failed to live up to these ambitious claims. For that reason, perhaps, we’ve stopped seeing them as elevated figures. It’s hard to imagine anyone outside an MFA program—and few people in them—taking the messianic claims of the Modernists seriously. Maritain, for his part, predicted as much:

And now the modern world, which had promised the artist everything, soon will scarcely leave him even the bare means of subsistence. Founded on the two unnatural principles of the fecundity of money and the finality of the useful, multiplying needs and servitude without the possibility of there ever being a limit, destroying the leisure of the soul, withdrawing the material factible from the control which proportioned it to the ends of the human being, and imposing on man the panting of the machine and the accelerated movement of matter, the system of nothing but the earth is imprinting on human activity a truly inhuman mode and a diabolical direction, for the final end of all this frenzy is to prevent man from resembling God. (39)

Having, predictably enough, failed to become a god, the modern artist falls into the hands of the market, the unstoppable forces of consumer capitalism—and ultimately stops being even an artist. His art becomes a status symbol for the rich; he is Jeff Koons selling his tacky Oldenburg imitations to billionaire industrialists for tens of millions of dollars. Koons’s real talent is not for art but for self-promotion; in a truly brutal essay from 2004, Robert Hughes said that Koons “has the slimy assurance, the gross patter about transcendence through art, of a blow-dried Baptist selling swamp acres in Florida.” In Koons and his counterparts—Bret Easton Ellis in fiction, Rupi Kaur in poetry, Taylor Marshall in theology, Dinesh D’Souza in history—we see the ideals of the modernists co-opted by the cult of celebrity (with the financial rewards it offers).

I’m being uncharitable, and you’re right to detect a whiff of ressentiment in my criticism of these artists and thinkers. The truth is that, almost despite myself, I want to be one of them. With every word I write, I imagine myself being praised for my wit and insight. It’s a cancer, malignant and menacing, attacking me at the very source of my work. I’m incapable of writing a word without imagining delivering it before an enormous auditorium; of keeping a journal without imagining future generations eagerly reading it; of reading a biography without imagining somebody writing my own. It’s a sickness, and despite the warriors in the Iliad literally dying for glory, I think it’s a peculiarly modern sickness—or at least a peculiarly modern form of an ancient and universal human sickness—and the product of a shallow culture that values popularity over truth and whose model of success is the teen idol or the rock star. Isn’t it strange that, long after rock has ceased to be popular music’s lingua franca, “rock star” continues to be the term we apply to the hyper-successful in business, academic, and other decidedly unhip arenas? No success in our society is truly success without a crowd, real or imagined, chanting your name.

Celebrity and Faithfulness

Really I suspect that the problem is not celebrity itself, but ambition and the worship of success in all its forms; celebrity is a mere subcategory, the most prevalent among millennials. Most of us are, I think, called to quiet, ordinary lives of faithfulness, the successes of which are largely invisible or at least unheralded. Many of the saints give us our model for this sort of quiet faithfulness. While some of them were famous and noteworthy people in their lifetimes, the vast majority of them were total nobodies as far as their societies were concerned. We know them today because they lived according to a radically different table of values: the virtues of the Kingdom of Heaven. Even then, there are tens, even hundreds, of thousands of saints whose names we don’t know, remaining anonymous and unknown in their faithfulness. The celebrity pastor is not the model—the model is the parish priest, faithfully saying the liturgy to his congregation, day in and day out for decades, without the vast majority of us ever learning his name. The poetry of R.S. Thomas and George Herbert limn the lives of these invisible clergy; as Thomas puts it in “The Country Clergy,”

They left no books,

Memorial to their lonely thought

In grey parishes; rather they wrote

On men’s hearts and in the minds

Of young children sublime words

Too soon forgotten. God in his time

Or out of time will correct this.

It’s a different sort of ambition, built on the topsy-turvy rules of the Kingdom of Heaven. The paradox of Christianity is that its successes look a lot like failures, as the body of Christ on the crucifix reminds us.

With this in mind, the best model that I know of for the Christian artist—and, by extension, the Christian intellectual—is J.R.R. Tolkien’s short story “Leaf by Niggle.” The title character is a kind of sub-sub-minor painter who spends his entire life painting a single tree, composed of incredibly detailed and loving paintings of individual leaves. But as he gets older, he begins to realize, to his horror, that the other forces in his life (particularly his needy, annoying neighbor, Mr. Parish) are making it impossible for him to devote the kind of attention to his painting that it deserves. (It’s hard not to think of poor Tolkien’s students constantly taking his attention away from The Lord of the Rings.) Niggle is in a particular hurry to complete his painting because he knows that he must soon go on a long journey, a clear allegory for death.

To Niggle’s credit, he doesn’t really think about the splendid public reputation that awaits him once he completes his painting; he cares only for the goodness and quality of the painting itself. That’s a good thing, because he leaves on his journey before he can finish it and is forced to abandon it to the people of his village, who completely fail to appreciate it. Near the end of the story, we are privy to a disheartening conversation between two of them; an important figure in the village government criticizes Niggle for wasting his life on the “digestive and genital organs of plants.” We learn that, after Niggle left town, his canvases were destroyed and put to use patching Parish’s damaged house. Later, a man called Atkins found a small corner of it and was oddly moved by it. Even so, neither Niggle nor his life’s work achieved any lasting recognizing or any real success:

That was probably the last time Niggle’s name ever came up in conversation. However, Atkins preserved the odd corner. Most of it crumbled; but one beautiful leaf remained intact. Atkins had it framed. Later, he left it to the Town Museum, and for a long while “Leaf: by Niggle” hung there in a recess, and was noticed by a few eyes. But eventually the Museum was burnt down, and the leaf, and Niggle, were entirely forgotten in his old country. (111-112)

It certainly seems like a tragic ending. Artists and intellectuals who seek success and reputation but fail to attain it can comfort themselves with the thought that many great thinkers have failed to be celebrated in their own time. But Niggle has been denied even the bittersweet posthumous reputation that someone like Herman Melville received.

But the phrase “his old country” betrays the fact that the reader’s attention has by this point been directed far away from the villagers’ values. Much of the story, in fact, follows Niggle on his journey into a sort of Purgatory, in which he learns that his painting was not the important thing in his life, that too often he used it as an excuse for neglecting his real duty: becoming a saint. His annoyance at Parish’s interruptions was a sign of his incomplete sanctification. His period of purgation teaches him to care for his fellow human beings, and eventually he wonders about Parish’s fate and longs to see him. This concern pushes him past the initial stage of sanctification, and something remarkable happens. He steps off a train, walks through a gate, and bicycles through the countryside before he sees something that knocks him to the ground: “Before him stood the Tree, his Tree, finished. If you could say that of a tree that was alive, its leaves opening, its branches growing and bending in the wind that Niggle had so often felt or guessed, and so often failed to catch” (103-104). His first thought is that this tree is a gift to him. His second is that the parts of it that were incomplete at his death had somehow been completed by Parish, who knew things that Niggle didn’t, such that “Some of the most beautiful [leaves]—and the most characteristic, the most perfect examples of the Niggle style—were seen to have been produced in collaboration with Mr. Parish: there was no other way of putting it” (104). His third thought is that the rest of the forest is incomplete and can be completed only with Mr. Parish’s help. The two move on to Paradise only once they’ve worked together to complete it, and learned to appreciate each other’s life’s work.

“Leaf by Niggle” is an effective check on the artist’s ambitions in at least three ways. First, the total obscurity into which Niggle and his work fall after his death ought to dispel the notion that celebrity is the artist’s or the intellectual’s metric of success. We’re not even made aware of Niggle’s ostensible failure until long after we’ve learned that it doesn’t matter. Second, the late appearance of the completed tree demonstrates that, despite being a real vocation—despite being worthwhile and worth pursuing—artistic and intellectual labor is not the most important work of our lives. Sainthood (our own and our neighbor’s) is, and if our work stands in the way of it, we must put our work aside. And finally, Parish’s role in the completion of the tree shows us that the achievements that we are so tempted to think of as ours alone (and celebrity is built on the notion of individual achievement, to be sure) are actually subtly but essentially collaborative. And even then they were just pieces of a larger tapestry, trees in a larger forest, a cause for the artist’s humility rather than her ambition. The mountains that Niggle lights out for at the end of the story are the Kingdom of Heaven, which he can understand and enter now that his table of values has been realigned to the Beatitudes.

Everything in life pushes against sainthood. St. John understood this: “Do not love the world or the things in the world. The love of the Father is not in those who love the world; for all that is in the world—the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches—comes not from the Father but from the world. And the world and its desire are passing away, but those who do the will of God live forever” (1 Jn 2:15-17). The artist and the intellectual are as tempted by these worldly desires as anyone else—maybe more than most people, since our culture sometimes values and rewards their work. And yet our work is, or at least can be, meaningful, even godly—particularly when it resists the false narrative of celebrity.

Our task must be to focus on the work and its internal goods, and on the kingdom of heaven that all our actions are meant to serve, rather than on the reception of our work. Even the professional is an amateur, in the sense that her work is not her true vocation—sainthood is—and in the sense that she cannot expect her work to survive. Perhaps it will appear, as Niggle’s tree does, completed and perfected by an act of grace, in the afterlife. But only God knows that. Our work in the meantime is like that of the home woodworker building a bookcase. He does not expect to be celebrated for his work, except in the most minor and domestic ways, and he knows that eventually it will fall to pieces. His job is to build something that will serve its purpose—something that will hold books and look good doing it. That’s our job, too: We build the poem or painting or essay to express the truth, goodness, and beauty given to us, and its reception and legacy ought to be beyond our consideration. And when we’re done, we leave the basement and get back to the real work of our lives: sainthood.

At the risk of of pushing you from arete to hubris, let me comment that this is a beautiful meditation. Thanks for writing it.

Comments are closed.