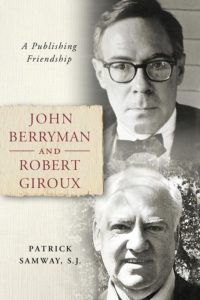

Waco, TX. As the late historian John Lukacs would insist, all stories as we know them and retell them are remembered. This means they are, inherently, personal. John Berryman and Robert Giroux: A Publishing Friendship is no exception. The book tells the story of the American poet John Berryman (1914-1972) and the renowned publisher—most notably, of T. S. Eliot and Flannery O’Connor—Robert Giroux (1914-2008). The premise of this work is the relationship between this poet and publisher, but its conception began with a friendship as well.

In an interview for Notre Dame press, Patrick Samway explains, “My impetus to write this book stems from my friendship with Robert Giroux, whom I knew for 20-plus years.” Following the publication of The Letters of Robert Giroux and Thomas Merton (2015) and Flannery O’Connor and Robert Giroux: A Publishing Partnership (2018), Samway saw this book as the natural next step, the completion of what he calls his “Giroux trilogy.” In Giroux’s retirement, Samway had full “access to his personal and professional files.” Samway recounts, “As I wrote this book, I felt I was on very solid ground.” This solid ground, of course, is particularly situated—toward Berryman, from the perspective of Giroux. What we receive is an incredibly in-depth chronicle of the intertwining lives of two academics, beginning with their time together at Columbia in the 1930s. We receive gossip, details, and letters in their entirety. We receive a stunning wealth of research and information. We receive the kind of inside perspective that only a personal friend could bring to this history.

In an interview for Notre Dame press, Patrick Samway explains, “My impetus to write this book stems from my friendship with Robert Giroux, whom I knew for 20-plus years.” Following the publication of The Letters of Robert Giroux and Thomas Merton (2015) and Flannery O’Connor and Robert Giroux: A Publishing Partnership (2018), Samway saw this book as the natural next step, the completion of what he calls his “Giroux trilogy.” In Giroux’s retirement, Samway had full “access to his personal and professional files.” Samway recounts, “As I wrote this book, I felt I was on very solid ground.” This solid ground, of course, is particularly situated—toward Berryman, from the perspective of Giroux. What we receive is an incredibly in-depth chronicle of the intertwining lives of two academics, beginning with their time together at Columbia in the 1930s. We receive gossip, details, and letters in their entirety. We receive a stunning wealth of research and information. We receive the kind of inside perspective that only a personal friend could bring to this history.

Samway leaves no stone unturned in providing the chronological details of the life and publication history of John Berryman. The seven chapters of the work chronicle Giroux and Berryman’s lives from childhood to Berryman’s death in 1972. During Samway’s account of their Columbia years, we receive insights into the courses they took, the grades they received, and the relationships they had with particularly influential professors, such as Mark Van Doren.

Van Doren believed that poetry need not be easily understandable but that it had to “say something,” affirming “the value of radically experimental prosody as long as it made sense from a human and epistemological point of view” (28). In Van Doren’s scholarship, we discover the nascent beginnings of Berryman’s mature poetic form, which would be most famously expressed in The Dream Songs. Columbia also found Giroux and Berryman working together—already as published poet and editor—foreshadowing “one of the most extraordinary personal and professional relationships in the history of American poetry” (29).

Following their relationship so closely means seeing inside its tensions. After Columbia, Berryman accepted a position at Cambridge that Giroux mistakenly rejected, and Giroux’s pain over the miscommunication lingers in the text, over 90 years after the fact. At Cambridge, Berryman would attend the lectures of T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden and meet W.B. Yeats, in what Samway describes as an “unfocused conversation” (39). Also during the Cambridge days, we see the beginning of Giroux and Berryman’s lifelong correspondence, and Giroux’s letters read with the desperation of a young scholar’s networking emails. Samway describes the letters as a kind of “plea” from Giroux for friendship.

Their correspondence, often represented in full in the text, gives the reader a glimpse into the beginnings of two scholars and academics who would become household names. Giroux would act as editor and publisher for an esteemed list of authors including Hannah Arendt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, Derek Walcott, Robert Penn Warren, Eudora Welty, Elizabeth Bishop, and T. S. Eliot. And while their halting, guessing style of correspondence never changes throughout their relationship, Giroux’s influence did. Giroux saw the role of a publisher as “an author’s close collaborator.” Samway details how Giroux helped Berryman navigate contracts and prepare for projects while also giving him realistic expectations and managing the red tape work that would have prevented Berryman from writing at all (61).

The book is a paginated archive of information. The great wealth of detail might make the text less readable but simultaneously more valuable for the scholar interested in the minutiae that gives life to new interpretations of an author’s life and work. Samway almost impossibly records the dates, grades, courses, and even dollar amount of honorariums and salaries. We learn the publication details of Berryman’ first major work, “Home to Mistress Bradstreet,” which Berryman calls “an attack on The Waste Land: personality, and plot—no anthropology, no Tarot pack, no Wagner” (121). We receive the long publication story of his most famous work, The Dream Songs. And, Samway details the lifelong process of Berryman’s critical work on Shakespeare, which was published posthumously. Along the way, we discover the decades of involvement on Giroux’s part to make sure these works did not remain trapped forever in Berryman’s mind and notes.

These scholarly details exist alongside of anecdotes and gossip about the “celebrities” of modernism, which slip in and out of Berryman’s world and the pages of the text. We read about Berryman’s visit to Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s hospital: “Berryman sat on the floor hugging his knees, asking, at one point, for Pound to sing an aria from his opera Villon” (69). We discover that Giroux once found T. S. Eliot in a classroom at Princeton, diagramming characters for his forthcoming play, The Cocktail Party. Eliot asks, “Have you noticed the sign, ‘Do Not Erase?’ That’s because Albert Einstein occasionally uses this blackboard for excursion into the fourth dimension. I wonder what he’ll think of my equations?” (71).

The detail that contributes to the interest and delight of the work also records the tragic note that resounds throughout Berryman’s life. The narrative is chronologically punctuated by visit after visit to hospitals and mental institutions, as Berryman recovered from a tragic succession of alcohol benders and drug overdoses. A friend recounts in a letter, “also saw John Berryman, utterly spooky, teaching brilliant classes, spending weekends in the sanitarium, drinking, seedy a little bald, often drunk, married to a girl of twenty-one from a Catholic parochial college, white, innocent, beyond belief, just pregnant” (119).

Berryman’s pendulum of health stemmed from and perpetuated the crippling insecurity he felt about his work. Berryman’s success was usually followed by a spiral into alcoholism and prescription medications. Berryman writes to Giroux, “You were right abt the Pulitzer and I was wrong: it doesn’t matter a straw—I’ve had much larger & more important awards—but believe me people think it does” (157). His letters are replete with heartbreaking pleas for affirmation, even as he was winning America’s most prestigious awards, including the Guggenheim, the National Book Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. One of his colleagues wrote to him, “As a loving friend, I am bothered at your wanting either criticism or praise, at this point with this urgency from them named above or from Mark or me… the only thing in your brilliant life I don’t envy is the hard way you have gone about being a great poet. But even that perverse and roundabout way is inextricable from the man and the work I love” (181).

Sometimes subtly and sometimes directly, the reader is reminded throughout the text that this story is told by Giroux’s friend. At one point, Samway points out, “Although Berryman subsequently apologized for any confusion he had caused, he continued to communicate in a most enigmatic fashion, putting even more burden on Giroux to decode his slipshod, fragmented sentences” (131). As seen in this instance, alongside of the reportage style, Samway allows himself to editorialize, often on the behalf of Giroux. This contributes to the distinctive tone of the work itself, as the book blends an overwhelming amount of historical detail with the kind of comments that can only stem from personal remembrances.

Perhaps the most surprising instance of this is Berryman’s conversion to Catholicism at the end of his life. We are given a factual retelling of this instance—almost so factual that it is hard to make sense out of it. Samway calls the series of events leading to Berryman’s conversion an “odd turn” in Berryman’s life and recounts it as “some type of religious conversion” (182). The tenor of this narrative indicates that it was an event about which Giroux, and therefore Samway, did not have the same kind of privileged knowledge. Samway explains that “Berryman became deeply interested in Christ, though he did not pray to him”—piquing our interest into how exactly we should understand this conversion experience and the poetry that came out of it (182). Berryman’s devotion, however, is not revealed. And just a few pages, and two years later, Samway records how Berryman leapt to his death on January 7, 1972, on the Washington Avenue Bridge, as his students watched.

It is this moment that we see the limits of this work—or any kind of biography. As much “inside” information as this book provides, it is also important to note what it cannot narrate: the inner life of Berryman, the details of his conversion, or the depression that caused his death. This book provides a wealth of information that will aid Berryman scholars for years to come. However, it might not make you fall in love with Berryman or his poetry, because it is his voice that is necessarily the more absent. It might, however, make you, like I did, Google The Dream Songs and attempt to decipher their enigmatic intricacy. It might make you sit with poetry that requires attention and time and try to listen carefully for Berryman’s distinctive voice.

Butler Library from the steps of Low Memorial Library, Columbia University.