Amarillo, TX. On a pre-Covid Saturday afternoon in Amarillo, I was having a beer with the poet Donald Mace Williams at a bar that was otherwise empty—save for one cowboy drinking alone. At 90, a lifelong newspaperman with a Ph.D. in Old English, Don has contributed his fair share to Texas letters, including an adaptation of Beowulf set in our forgotten section of Texas called the panhandle. Around Beer #2, we began discussing the works of Larry McMurtry. Don proclaimed loudly that he believed Lonesome Dove was a farce. The cowboy down the bar perked up at the mention of the novel.

“Lonesome Dove is the greatest book ever written,” said the man, pushing back his Stetson.

Don, undeterred, said it again. “It’s a farce. McMurtry thought the Western was dried up, and then he wrote one!”

The cowboy squinted down the length of the bar, sizing up the old poet. For a moment, I felt Don had just drawn me into a fist fight with a stranger.

“I don’t know about all that,” the cowboy mumbled. “It’s just a great book.” He pulled his hat down and returned to his beer.

In the fall of 1960—as Wendell Berry was wrapping up his stint as a Stegner fellow—McMurtry also entered the famed seminar at Stanford. Literary giants who crossed orbits always draw attention, retrospectively. I want to pencil lines between these stars and make constellations. I think of Paris or Oxford in the ‘20s.

I am a son of west Texas, and McMurtry was our encompassing literary atmosphere. I was eight when the Lonesome Dove miniseries broadcast our landscape into living rooms across America.

I am also the son of a small-scale farming father, and Berry’s well-worn The Gift of Good Land occupied nearly every level surface in our house as Dad would set it down and return to it for fortification. When, as a burgeoning writer, I learned of their proximity, I imagined Stanford in the ‘60s to be a moveable feast of arguments about Horseman, Pass By and Nathan Coulter.

Alas, Berry and McMurtry merely passed by each other like a comet missing an asteroid. Nevertheless, it’s clear that they became aware of each other then. Perhaps that small gravity affected their trajectories.

The other astral line I might pencil in connects both these authors to their shared teacher, Wallace Stegner, the luminary of the American West and champion of place. But Stegner was on sabbatical for McMurtry’s one year at Stanford. Still, the program Stegner designed must have produced similar effects on different students, even in his absence. Allow me to table Stegner for a moment.

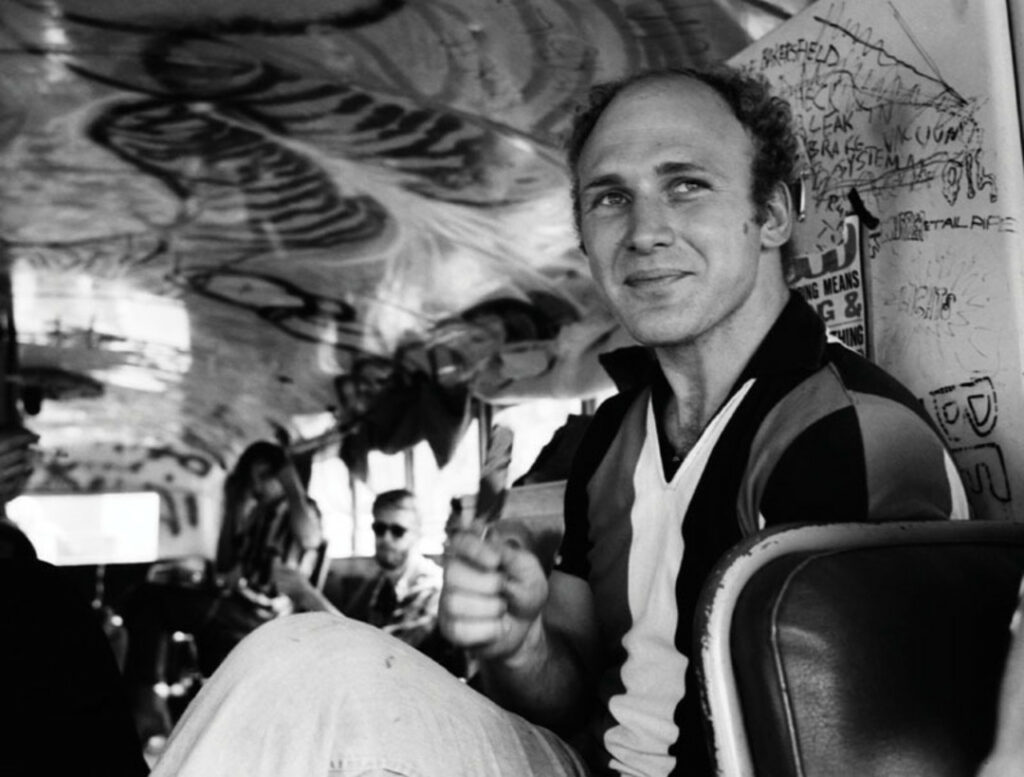

The more remarkable literary relationship that McMurtry formed at Stanford was with the cocksure Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, who was attempting to bridge the gap between the Beats and the hippies. Kesey and a band of merry pranksters (his term) eventually fled a California drug charge on an acid-induced road trip, careening across the country in a Day-Glo painted school bus. In the mode of Kerouac, they were pioneers short a frontier. They briefly sought sanctuary with McMurtry in Houston, an episode famously chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. A more polar opposite of Wendell Berry could only be found in a coal-mining executive.

Ted Giddens—a utility coach at my high school and mentor to a generation of Canyon High graduates—proudly displayed the Lonesome Dove tetralogy on the mantle in his living room. For him, that solid foot of bookshelf represented the height, but not the breadth, of fiction he’d read in his adult life (along with some Louis L’Amour, a writer whose mythology McMurtry managed to lampoon and fully realize in Lonesome Dove). Now in his seventies, Ted’s a lifelong student, always reading books on leadership, business, and the great achievements of men. Augustus McCrae and Capt. Woodrow F. Call seemed to fit neatly into all of those genres.

He retired from coaching and began delivering radio play-by-play for high school football games throughout the panhandle. His baritone, which once barked boys to attention on the sun-baked practice field, now drifted across a piece of land the size of West Virginia, but with fewer ears than Tulsa.

I visited Ted after college. He asked me what I expected to do with an English degree. I told him that I would like to write stories. He rumbled in his announcer’s cadence, “McMurtry’s your answer.”

Back to Stegner. He was publicly disappointed with the restless, Ken Kesey strand of writer that emerged from his workshop. But Stegner was also publicly disappointed in the restlessness of his own upbringing, describing himself as “born on wheels” and “shaped by motion.” When he was able to finally settle onto a Palo Alto plot of land in 1945, he became a “placed” person until he was killed in a 1993 car accident.

In his essay “The Sense of Place,” he understands that “every American is several people . . . and one of them is . . . the displaced person . . . the inevitable by-product of our history: the New World transient.” And “[c]ulturally he is a discarder or transplanter, not a builder or conserver. He even seems to like and value his rootlessness, though to the placed person he shows the symptoms of nutritional deficiency, as if he suffered from some obscure scurvy of the soul.”

If on that essay’s exhale he mourns the malnutrition of the transient, then he also inhales the oxygen of the deeply rooted, placed person. In the essay’s final movement, Stegner nearly sings, “No place . . . is a place until it has had that human attention that at its highest reach we call poetry. What Frost did for New Hampshire and Vermont, what Faulkner did for Mississippi and Steinbeck for the Salinas Valley, Wendell Berry is doing for his family corner of Kentucky.”

I’d add simply: what Berry is doing, McMurtry has also done for west Texas.

Mason Rogers, an Amarillo architect, told me that reading Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen validated his love for west Texas. “I read it when I was in college,” he wrote in an email.

After moving to Austin [from Amarillo], McMurtry felt like kinfolk to me. I could hear my grandparents’ voices in his writing style, and I had certainly spent time pondering my place in the world while sitting in a Dairy Queen. In architecture graduate school in Washington, D.C., we read several essays by Walter Benjamin, and I started to see the full circle. McMurtry read Benjamin and made connections to the storytellers. I read Benjamin’s works about architecture that would inform my design philosophy.

Walter Benjamin was a little dark, and his appreciation for architecture sometimes seemed like it was only because it is a durable art and can be used to describe the flaws of the previous generations. McMurtry could get a little dark, too, but it always seemed like his brooding grew out of his affection for this place and his disappointment in its inhabitants (like any good idealist). I think this is the perfect kind of angst to inspire great art.

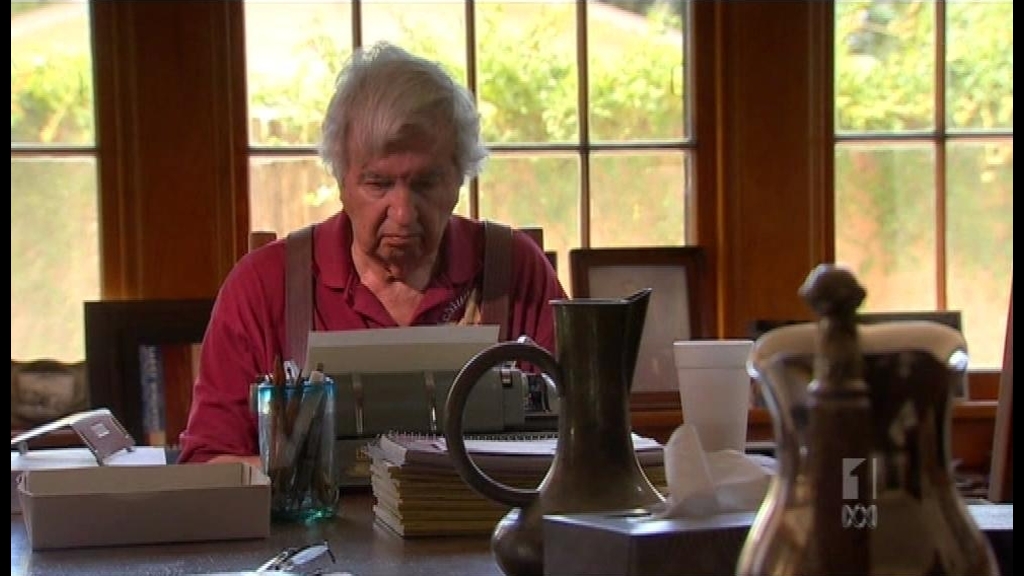

Mason’s observation that Benjamin used architecture to criticize his ancestors strikes me as I’ve been rereading McMurtry in the week since his death. Especially in Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen—which one reviewer called “as close to an autobiography as you’ll get from McMurtry.” The book is centered around the scorching summer of 1980, when, in a “Slough of Despond” he returned to his tiny hometown of Archer City for its centennial celebration. Hiding from the heat in a Dairy Queen, he read and reread Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller.” He describes it as a profound examination “of the growing obsolescence of . . . practical memory and the consequent diminution of the power of oral narrative in our twentieth-century lives.” McMurtry could certainly slide up and hit that high, scholarly note when he felt like it.

Throughout the book, he presents himself as the sole, trustworthy reliquary of Archer City’s stories: “I planned to casually inquire of the locals what they could actually remember of the country’s majestic century-long history. By choosing the Dairy Queen I would eventually encounter virtually everyone who lived in the county. But in fact, my examination of local memory was over almost before it had begun . . . because all anyone could remember with any precision was the local deaths.” His point was Benjamin’s point: the collective memory of the front porch storytellers had been outsourced to technology, media, and even writers like himself. McMurtry remembered the strange people (a mute woman who’d been sold for skunk pelts); curious events (LBJ landing a helicopter on the courthouse lawn to hand out peaches); and historical moments (FDR’s staticky declaration of war)—either that or he’d done some research about his town’s early years—but it seems no one else in Archer City recalled these stories. He hoped their memory would be some durable art—like Benjamin’s architecture—but it turns out that Archer City’s lack of memory was both the thing that endured and the point at which he criticized previous generations.

His criticism wasn’t a scorched-earth dismantling though. Five years after reading Benjamin’s essay in the Dairy Queen, McMurtry published Lonesome Dove. He famously and consistently was attempting to “demythicize” that section of history which Westerns exploit for its myth. He famously failed (as Don Williams told that cowboy). Gus and Call might have ridden with McMurtry’s own Texas Ranger uncle; they could have driven their stolen Mexican cattle across the McMurtry family ranch on their way to Montana. McMurtry couldn’t quite set the Bowie knife to the scalp of the Western like Cormac McCarthy did the same year, maybe because he knew those people weren’t grotesque caricatures; they were people he’d known and loved. And when he died last week, he was probably the last person in Archer City who had any connection to those people at all.

In a public letter to Wendell Berry, Stegner acknowledges that readers often make a natural comparison of Berry to Thoreau for their “reverence to the earth.” But he says, “Thoreau seems to me a far colder article than you have ever been or could ever be. . . . Your province is not the wilderness, but the farm, the neighborhood, the community, the town, the memory of the past and the hope of the future— everything that is subsumed for you under the word ‘place.’”

I’d make a similar comparison, then distinction, between Berry and McMurtry. Even though McMurtry is our local hero, and our place has become a place because he paid it such thorough attention, he is a colder article than Berry.

Their similarities begin at their point in history. They were acquainted with people from the previous century. They grew up with Benjamin’s by-gone storytellers. Here’s McMurtry in Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen:

In the evening, once chores were done, people sat on the front porch (if it was summer) or around the fireplace (in the winter) and told stories. None of these stories were ever told to or directed at me; none of the Slovenly Peter, this-is-a-warning-little-boy stories ever came my way. But I was allowed to listen to whatever stories the adults were telling one another.

And here is Berry in The Hidden Wound (which McMurtry reviewed for The Washington Post):

It is of some importance to try to say exactly how these stories were handed down. It would be easy to allow the impression that the past and its assumptions were deliberately and consciously planted in my mind by my elders. But that is not at all the way it was. The various households of my family were always visiting back and forth, and I spent a lot of time as a child listening to the grownups’ talk— the ever-circling patterns of reminding that carried their thoughts from the present to the past.

Berry’s project in The Hidden Wound, by the way, was to confront as honestly and rigorously as he could manage the sin of racism in his and his community’s imagination. A sin as dark as west Texas’ own Red River Wars, which finally annihilated the Plains Indians. “I want to be cured,” Berry continued “I want to be free of the wound myself, and I do not want to pass it on to my children.”

Whereas Berry has in mind the life of his community’s children, McMurtry seems resigned that the future of Archer City—his neighborhood, community, and town—are bound to die like so many other small towns in west Texas. In Skip Hollandsworth’s Texas Monthly obituary of McMurtry, he noted the author had lately changed his funeral plans from a cemetery plot in Wichita Falls to an urn in his Archer City bookstore. His final act then is to be interred in his reliquary of stories, and his local death will join the others in being remembered with precision.

If McMurtry couldn’t bring himself to hope as explicitly as Berry does, he also couldn’t help spinning the yarns of his community and its place. I know the cowboy in that Amarillo bar, and thousands more like him, will share his stories for years to come.