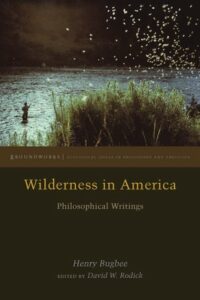

Waco, TX. The 2017 publication of Wilderness in America: Philosophical Writings, a collection of essays by the American philosopher Henry Bugbee, should have sparked a revival and celebration of one of America’s deepest thinkers in the 20th century. That it hasn’t testifies to the quiet, abiding character of the man that shines forth from these pages, indeed also to the quiet, abiding character of thinking itself.

Henry G. Bugbee was born in 1915 in New York City to an affluent family. He attended prep school, spent seasons off fishing with his father in the mountains. He studied philosophy at Princeton thereafter, hoboed with friends to Wyoming to work on hay farms during the summers. He went on to doctoral work at U.C.-Berkeley but struggled in its stifling atmosphere, only to solve his writer’s block by serving as a naval captain in the Pacific during WWII. He returned after the war to write his dissertation, then became professor at such institutions as Stanford, Chatham, and Harvard; accepted the consequences of not publishing by being denied tenure at the latter, then struck out for the University of Montana with the aim of building one of the nation’s best philosophy departments. He fought with administrations, resigned from his job, went on speaking tours, got his job back again, built the honors program he had wanted, then retired in 1979. All the while, he fished. He died in 1999, and a memorial service at the University of Montana did not have enough room for all the attendees.

Henry G. Bugbee was born in 1915 in New York City to an affluent family. He attended prep school, spent seasons off fishing with his father in the mountains. He studied philosophy at Princeton thereafter, hoboed with friends to Wyoming to work on hay farms during the summers. He went on to doctoral work at U.C.-Berkeley but struggled in its stifling atmosphere, only to solve his writer’s block by serving as a naval captain in the Pacific during WWII. He returned after the war to write his dissertation, then became professor at such institutions as Stanford, Chatham, and Harvard; accepted the consequences of not publishing by being denied tenure at the latter, then struck out for the University of Montana with the aim of building one of the nation’s best philosophy departments. He fought with administrations, resigned from his job, went on speaking tours, got his job back again, built the honors program he had wanted, then retired in 1979. All the while, he fished. He died in 1999, and a memorial service at the University of Montana did not have enough room for all the attendees.

Such a full life, fit more so than most academics for a biography of its own, leaves one wishing that as many scholars today would attend to Bugbee’s work as there were at his funeral. (Apparently, he left a lasting impression on everyone he met, whether professors like W.V.O. Quine at Harvard or the conservation community in Missoula.) But it is just as well to attend to his writings presented here, as this collection of essays shows that the life Bugbee lived was apiece with the thoughts he wrote and taught.

The collection begins with an introduction by David W. Rodick, wherein he outlines Bugbee’s life and legacy and then gives a brief philosophical overview of these essays. He suggests that Bugbee can best be understood as proposing an “experiential naturalism,” i.e. recognizing “the need to address beings experientially on their own terms, within the natural context out of which they emerge, in an effort to see what can be revealed once beings are beheld in their own light” (6). To cite Bugbee himself: “Things say themselves, univocally, unisonously, formulating a tautology of infinite significance” (6). Out of this “nonreductive naturalism” Rodick argues that there arises “the possibility of discerning the eternal amid the temporal” (7). Rodick offers a fine introduction that prepares the reader well for the essays ahead. Before each selection he also gives a short précis that organizes the sometimes-meandering flow of Bugbee’s thoughts into a coherent whole, which makes these texts more approachable for a wider audience of readers. Nonetheless, I will suggest a somewhat different interpretation than his. With attention to the subtle religious undergirding of his thought, one finds that Bugbee’s work suggests not only an experiential naturalism but, even more, an existential realism—a way of thinking that recognizes the separate and perduring significance of the things themselves, the world itself and the revelatory character of being as such, even as it privileges our peculiarly human participation in all these things.

Part I consists of selections from Bugbee’s undergraduate thesis and his dissertation. Part II presents three of the rare essays published during his lifetime. Part III has four previously unpublished writings, all of which meet the standard of the published just as well. And Part IV is an interview of Bugbee given by his wife Sarah and his friend Ray Lanfear. It is touching, full of anecdotes spanning the narration of his life, and it gives the reader some understanding of why those who knew him had such affection for the man. The book concludes with some appendices consisting of his curriculum vitae, some letters and journal entries, poems dedicated to him, and other miscellany.

These selections are varying and unsystematic, but through them all, from Bugbee’s undergraduate thesis to the interview recorded near the end of his life, strikingly coherent themes persist. The first of these is his thought’s religious impulse—a fact yet to be appreciated by American theologians. As Bugbee himself explains in the interview, his undergraduate thesis came “mostly out of concerns of becoming fundamental in the writings of St. Paul” (147), and each chapter thereof begins with a quotation from the Apostle. Much like for Martin Heidegger in 1922, the fundamental Christian experience of Paul opened to Bugbee the possibility of thinking existentially about the ultimate structures of reality itself. The other writings suggest an interreligious attitude throughout, peppered as they are with mentions of the Bhagavad Gita and Buddhism as much as Christianity. His essay “A Venture into the Open” takes an ecumenical tone as it attempts a sort of foundational posture for all meditative modes of thought. But it seems the Bible and Christian theology influenced Bugbee most. Take one example: in the essay “Thoughts on Creation,” he goes through the various myths of creation in ancient religions and then gives a general definition of the divine: “utterly simple, presiding, gathering, disposing, revealing Presence… imparting the very gift of speech, in which the being of beings is consummated” (76). It is vague and 20th-century-philosophical enough. But he then (without noticing, it seems) focuses on a decidedly unmythical doctrine of creation, creatio ex nihilo. In a fact that disagrees with Bugbee’s lumping of it with mythic thought, this doctrine had arisen, historically, as a polemic against all previous ancient and polytheistic accounts that had put ontological continuity between creator and creature, god and man. Instead, it arose just to assert that creation does not come out of god or mythic divine fertility but rather out of nothing—and thus, as Bugbee hints, as sheer gift, gratuity. He suggests being itself is of this sort, and he confirms this suggestion in his “A Way of Reading the Book of Job.” Here he meditates on revelation, theodicy, and, in the midst of desolation, faith—in what? In “the significance of things and events entering into human life” (124), but a significance without comprehensive signification of anything outside of itself. Rather, it is a “mutual address” with the things of the world whose raison-d’être is nothing but L’être-même (126). Here Bugbee suggests that a biblical faith arises from and returns to the sufficiency of reality itself.

The next theme, which emerges from this religious impetus, is the integrity of nature as an interrupting and abiding force that gives rise to genuine philosophizing. As early as his dissertation, he allows nature to interrupt his argument to give voice to it further. Here is one moment of his contemplating an evening snow: “As if in the completeness bestowed by a self-knowledge, this world now shines forth fully and limitlessly, accentuated in the light which it intensifies. Ere this light fades into night, what stands out so clear and distinct? What but the absolute presence of things, transfigured through the presence of snow?” (50). In the face of contemporary trends that deconstruct worn notions of a nature independent of a human artifice or that predict the coming reality of the Anthropocene, Bugbee’s thoughts here suggest a defiant confidence that the things themselves can and do reveal themselves to us in their independence, if only we would have the patience to let them. The main thrust of his essay “Wilderness in America” is that “wilderness” is “a place which will not let one off the metaphysical hook” (91). When one is in the wilderness, “one is brought to realize that one is held within the embrace of what is proffered in its being proffered. No behind or beyond the things themselves” (91).

But I cannot describe his thoughts on nature without moving straightaway to the jointure of the whole work, an existential realism, and here is where I must use somewhat different wording from Rodick’s. What distinguishes Bugbee from the common tropes of existentialism and pervades each of his essays here is his concern to sustain concepts of objectivity and reality in the face of vulgar relativism or positivism. This is already suggested by his treatment of nature as the “metaphysical hook” that refuses to let us off of the inescapable reality of things beyond our manipulation, comprehension, and construction. For Bugbee, both nature and the thinking it gives rise to force reality upon us. What is this reality? In “Nature and a True Artist” he answers: “Concrete reality, then, is accordingly being conceived as occurring, and occurring in the modality of meaning… in so far as concrete reality is, the force of this is can be at once in the indicative and the imperative mood: it would be a destinate affair” (112). Let that sentiment sink in for a moment: something both indicative and imperative—that would be the philosopher’s holy grail, would it not? For it would allow the philosopher to say that the facts of the matter he is dwelling upon, this life he is living and this reality he is encountering, matter, have something (and something quite important) to say to him, and to us. It would mean that the philosopher need not be doomed to look evermore into a mirror and speak forth his proclamations from that isolation. It would mean he could listen to what this world indicates, and then he might speak to us about it.

Reality, at once indicative and imperative, is what concerns us, but in such a way that it addresses us and we subsequently respond, not the other way around. In his “Notes on Objectivity and Reality,” Bugbee puts it even more forcefully: “we are objective then when we submit to the control of what presents itself” (128). And it is interesting that, here, he returns to the religious sentiment, referring his sense of objectivity and reality back to the Book of Job, a sense of “reality as basically just that which requires appreciation of us” (129). By “existential realism,” then, I do not merely mean Bugbee’s epistemological confidence in the reality of things but rather his ontological privilege given to the world as a reality which beckons to us.

By calling this sense of reality an existential realism, I hope to point to where Bugbee has something to say to us today, particularly in three contexts I consider essential: theology, philosophy, and ecology. Indeed, such notions as objectivity, reality, pure nature, and so forth seem out of place in all three now. In a “post-truth” era that takes for granted the idea that all reality, to an extent, is constructed, there is something refreshing, transfiguring, and above all humbling in the argument that our primordial condition is not one of mastery, speech, and construction, but one of submission, listening, and following. And anyone who might consider such postures totalitarian or tyrannical should listen closer to the freedom and pathos Bugbee’s thoughts exemplify. He offers the philosopher the chance to dwell anew on the nature of reality beyond logic, language, or social construction, and to revisit the existential thinkers so crucial to Bugbee himself—Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Marcel—and consider them in a realist light as defined by Bugbee above. And to the ecologist, he argues for the philosophical need of such notions as “wilderness” for a human posture toward the world, imperiled as such realities are in the Anthropocene. One looking for a deep philosophical defense of a kind of wilderness doctrine for ecology will find it in these pages.

But Bugbee offers perhaps the most beneficial conversation to the Christian theologian. American theology in particular has a long tradition of metaphysical realism, whether derived from such varying influences as Scottish common-sense philosophy or the process thought of Whitehead. But since Karl Barth’s forceful critique of natural theology—indeed, of the concept of a pure nature at all—much of Christian theology has avoided language of metaphysical, non- or pre-theological concepts of being, nature, and existence as such. The arc of Bugbee’s thought here suggests that the Christian impulse itself may lead to an appreciation of the independence and objectivity of nature and existence, apart from a comprehending “worldview” or narrative (even a so-called Christian one!). Relatedly, however, the theologian may pose to Bugbee: in all the attention you have given to the religious, meditative, and prayerful, what about a consideration to the thing itself of Christianity: the God of Israel, the Christ, Jesus of Nazareth? Can you assume the reverent posture found in Paul but leave his object of reverence behind for a kind of secular religiosity? Could it be that Paul’s (and Luther’s and Kierkegaard’s) fundamentally anti-religious breakthrough—the irruption of the risen Christ into this world through grace—and not an ecumenical, meditative openness, is what calls us to reality itself? Bugbee, himself a reader of Kierkegaard and Tillich, must have known about this distinction between the religious and the Christian in the mid-20th century and its debate. I wish he had addressed it. However, that absence may prove a gift of itself, for it allows theologians today to take these questions up anew.

But above all, Henry Bugbee’s writings left me with questions about the problem of a sort of intellectual evil—of course an evil less terrible than massacres and hurricanes, but one still depressing in its own right: why, of all the thinkers to have shot up into the spotlight and fall back out of it, did Bugbee never get his moment? Why doesn’t Bugbee have a place in the history of American philosophy, perhaps next to Nagel, just before the era of Rawls? I do not doubt that if he had received the attention he deserves, the American academy today would be a more philosophical, moral, and reverent place, if only by a small measure. Some blame might be owed to his own quiet refusal to play the game, to publish or perish. But is that a fault, or is it a courage that does not take part in the problems afflicting academia, problems which keep actual thinking from happening at all? In either case, however, students do not read Bugbee, with few exceptions here and there, one of them being the accident that put this book in my hands.

But here I was, flustered that Bugbee does not own the merits for races which he refused to run. And perhaps that speaks more to how little we should attend to these races than to how crooked the rules for them are. Perhaps the problem is not that the arc of intellectual history bends toward the wrong thinkers but that I was thinking according to the confines of introduction-to-philosophy textbooks. And this realization led me to reflect further upon how much this book of essays taught me. For even as I wished that Bugbee had a more prominent place than the one allotted to him, his wisdom turned me around on my own priorities and inched me closer to what really matters. And what matters is not that Bugbee receives a few dissertations about him, a philosophical school in his honor, or some think-pieces in The Atlantic that get shared on Twitter, but rather that his funeral couldn’t fit everyone who wanted to attend; that his students cared enough to collect these writings into a book for those willing to venture into it; that the philosophic life is made up more of communities and conviviality than of perduring intellectual trends.

But here I was, flustered that Bugbee does not own the merits for races which he refused to run. And perhaps that speaks more to how little we should attend to these races than to how crooked the rules for them are. Perhaps the problem is not that the arc of intellectual history bends toward the wrong thinkers but that I was thinking according to the confines of introduction-to-philosophy textbooks. And this realization led me to reflect further upon how much this book of essays taught me. For even as I wished that Bugbee had a more prominent place than the one allotted to him, his wisdom turned me around on my own priorities and inched me closer to what really matters. And what matters is not that Bugbee receives a few dissertations about him, a philosophical school in his honor, or some think-pieces in The Atlantic that get shared on Twitter, but rather that his funeral couldn’t fit everyone who wanted to attend; that his students cared enough to collect these writings into a book for those willing to venture into it; that the philosophic life is made up more of communities and conviviality than of perduring intellectual trends.

And that lesson reminded me of my own beloved professor at my alma mater: a private man who rarely published but affected every student he had. I suspect he is cited in more dissertation and thesis acknowledgments than articles. I will cherish always the conversations we shared. And I will never forget this quote by Alfred North Whitehead he had posted on his office door:

It must not be supposed that the output of a university in the form of original ideas is solely to be measured by printed papers and books labeled with the names of their authors. Mankind is as individual in its mode of output as in the substance of its thoughts. For some of the most fertile minds composition in writing, or in a form reducible to writing, seems to be an impossibility. In every faculty you will find that some of the more brilliant teachers are not among those who publish. Their originality requires for its expression direct intercourse with their pupils in the form of lectures, or of personal discussion. Such men exercise immense influence; and yet, after the generation of their pupils has passed away, they sleep among the innumerable unthanked benefactors of humanity. Fortunately, one of them is immortal—Socrates.

My professor knew what he was doing. Bugbee did as well. And now perhaps I am learning, thanks to the two of them, as well as the other “innumerable unthanked benefactors of humanity.” Perhaps you, reader, may pick up Wilderness in America, and we may both learn more together in due time, as we live the examined life and submit to the indicatives and imperatives that this “destinate affair” has in store for us.