“Berry Center Journal.” The summer issue of the Berry Center Journal includes several fine pieces. For instance, Jason Peters has an essay on security and locality, and Kate Dalton interviews Wendell Berry about COVID, co-ops, and where to begin doing good work.

“Writing in the Sand.” Christian Wiman ponders a story from the gospel of John and reflects on poetry, faith, and doubt.

“Yours, Mine, or Ours.” Gracy Olmstead reviews a book about fracking in rural PA: “In the United States, the way we draw property lines tempts us to think of our lived experience as segmented into neat little packages, in which each person is free to act without consequence. But as Up to Heaven and Down to Hell documents, each action within a local ecosystem inevitably bleeds into others, slowly helping or harming the whole.”

“Why We Don’t Dump Friends Who Disagree.” Bonnie Kristian praises the gift of friendship: “Affection, I’ve begun to suspect, is what too many of our relationships are missing. Its absence is why they aren’t wearing very well, why they struggle to bear up under the pressure of political polarization, theological divide, or other ideological difference. Perhaps we’re missing affection in this transient, testy, isolating age because we won’t hold still long enough for it to accumulate.”

“One by One, My Friends Were Sent to the Camps.” This is a moving, tragic, and humane account by Tahir Hamut Izgil of what is happening in Xinjiang.

“Come Labor On: Restructuring for Healthy Ecologies of Faith.” Mark Clavier wrote a three-part series on how to revive the Church in Wales. As he concludes in the final essay, “It wasn’t my intention when I began this series to rely so heavily on the metaphor of farming. The writing of them, you might say, has convinced me of its worth. Perhaps, we really need to begin with a conversion of our governing metaphor: the Church is much more like a farm than a corporation or business.“

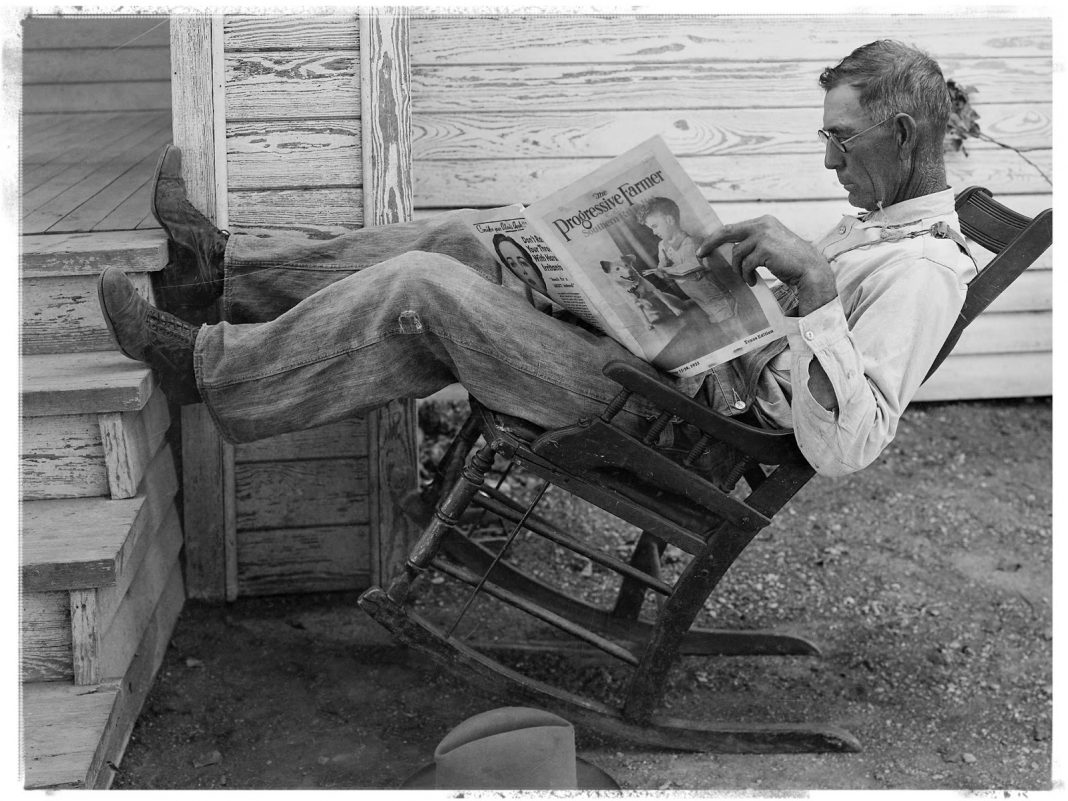

“Farmers Will Soon Have the Right to Repair their Tractors.” Greta Moran discusses how Biden’s executive order aims to prohibit companies from making it impossible for farmers to fix their own equipment.

“How to Teach History.” Matthew Walther responds to the “education wars” by arguing that the two loudest sides in today’s battles are missing the point of history and education entirely: “Properly understood, all education begins with wonder, with feelings of awe and impressions of beauty and strangeness.”

“What Happens in Left-Behind Places Doesn’t Stay in Left-Behind Places.” Christie Purifoy reflects on Gracy Olmstead’s Uprooted: “This is a book about places, but it is also a book about limitations and dependence. We need one another, and we need roots. We also need limits, and the fewer limits we have, the greater our need for discernment amidst a consumerist culture of almost endless choice.”

“John Ruskin vs. the Paris Commune.” Seamus Flaherty compares Ruskin to Christopher Lasch and commends the relevance of his vision of socialist organizations. As he concludes, “a Left with room for Ruskin on it is immeasurably more intelligent than a Left with room only for Foucault and Marx.” (Recommended by Adam Smith.)

“Feeling the Drought on my Family Farm.” Farmer and writer David Mas Masumoto reckons with drought: “At the heart of our farm lies a Japanese aesthetic captured in the meaning of wabi-sabi: Life is imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. The drought exposes the inconsistency of nature and how the “perfect” peach must reflect the imperfect weather we all experience.”

“Watching The Watchmen.” In a reminder that the 24/7 news cycle often spreads more heat than light, in-depth reporting by Ken Bensinger and Jessica Garrison complicates the story about the plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. FBI informants appear to have played a key role in not just uncovering the plot, but also in furthering it: “Working in secret, [these 12 informants] did more than just passively observe and report on the actions of the suspects. Instead, they had a hand in nearly every aspect of the alleged plot, starting with its inception. The extent of their involvement raises questions as to whether there would have even been a conspiracy without them.”

“Men in Dark Times.” Rebecca Panovka draws on the work of Hannah Arendt to develop a taxonomy of political lies: “Trump’s lies were not more convincing than those of other presidents; they opened the curtain on an epistemic crisis because they were less convincing, more flagrant. Trump was often accused of “saying the quiet part out loud”—revealing the open secrets politicians generally avoid acknowledging. The rhetorical effectiveness of Trump’s taboo-breaking proved the same thing Arendt gleaned from the Pentagon Papers: the American people already know their politicians aren’t telling them the truth. Trump did not need to create a make-believe world, because he appealed to those who had already lost confidence in the official representations of American political reality.”

“The California Dream Is Dying.” As observers such as Joel Kotkin have been warning, California faces real economic and cultural challenges. Conor Friedersdorf tackles its thorny problems in a long essay for the Atlantic: “blue America’s model faces its most consequential stress test in one of its safest states, where a spectacular run of almost unbroken prosperity could be killed by a miserly approach to opportunity.”

“Thinking Little About Climate Grief.” Matt Miller reviews Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church, an anthology of essays that lament ecological death and loss. Matt draws on Wendell Berry to assess what modes of grief are appropriate and necessary and what modes may be counterproductive.

“Turning Homeward.” Josh Pauling describes the small steps his family has taken over the last years that have led them toward a more family-centric economy and life.