Boise, ID. I had no intention of becoming tree-obsessed. But my own childhood in the woods of Idaho, my love of Tolkien’s Ents, and a spate of recent books about the magical ecosystems of forests have turned me into a forest enthusiast. I find myself writing about trees not only in reviews of books about trees, but in other ostensibly unrelated contexts. And, I find myself longing more and more for the forest and trying to find ways to be in it: to breathe the air, to walk on the leaves and needles, and to soak up the silence.

Suzanne Simard is one of the leading forestry scientists and a pioneer of the investigative work that has led to our current understanding of the interdependence of tree species with one another and with the fungi that inhabit the forest floor and their root systems. Peter Wohlleben cites her research in his popular text The Hidden Life of Trees and Merlin Sheldrake built extensively on her work in his research and in his own work of popular science in Entangled Life.

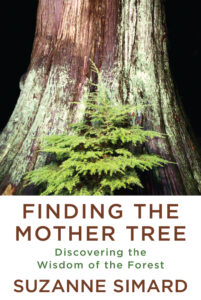

Knowing her scientific reputation, I expected Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest to be a densely reasoned overview of her years of research. The blurbs on the jacket and the inside flap did little to dispel this expectation and I put off reading it for a week after its arrival because I felt myself mentally tired and unready for academic-ese after a long year of teaching. Once I started it, though, I was surprised to find myself drawn in by a lyrical memoir: a life story interwoven with scientific insights and solid reasoning. Early chapters emphasize the theme of mystery and the hope of wisdom. But this is not a squishy feel-good story. Nearly every chapter includes detailed descriptions of carefully designed experiments, data analysis, and thoughtful exploration of the implications and insights they produced.

Knowing her scientific reputation, I expected Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest to be a densely reasoned overview of her years of research. The blurbs on the jacket and the inside flap did little to dispel this expectation and I put off reading it for a week after its arrival because I felt myself mentally tired and unready for academic-ese after a long year of teaching. Once I started it, though, I was surprised to find myself drawn in by a lyrical memoir: a life story interwoven with scientific insights and solid reasoning. Early chapters emphasize the theme of mystery and the hope of wisdom. But this is not a squishy feel-good story. Nearly every chapter includes detailed descriptions of carefully designed experiments, data analysis, and thoughtful exploration of the implications and insights they produced.

Starting in her childhood when she literally ate dirt from the forest floor, with reflections on the forestry legacy in her family, Simard moves through her summer jobs, her graduate work, her marriage, groundbreaking research, children, professorship, divorce, a new love affair, and her cancer diagnosis while painstakingly describing the life of various kinds of forests and forest animals, Canadian forestry management policies, and the trauma of academic battles. Simard’s work has been revolutionary but her account of it is humble, communal, and open. She recounts the tension she felt as a young female forestry researcher coming up against older, established, male policy makers and supervisors, and she is open about the internal tension she experienced trying to stand up for biodiversity and for the results of her research while not antagonizing them and while attempting to preserve her principles. She seems to desire toughness and bravado while embodying resilience and adaptability.

Simard’s earliest work involved poisoning the forest with glyphosate (Roundup). The contradiction of using harsh herbicides while believing in a less invasive forestry management system troubled her deeply. She had to continually remind herself that this research could lead to less interference in the ecosystem but the combination of killing plants and her own physical suffering from exposure to the herbicide was stressful in a way that echoes through the rest of her work. As she used radioactive isotopes to measure carbon movement and soil moisture levels she worried about cancer: a fear that later comes true. As she studies the interdependence of trees with their kin and neighbors, she reflects on the demands of an academic career that left her exhausted and far from her children.

From early studies showing that aspens benefit the Douglas firs planted near them, to careful tracking of the effects of healthy forest soil full of fungal life versus sterilized soil, to kin studies analyzing the relationship of older trees to their genetically related seedlings, Simard demonstrates that it is not just generic biodiversity that is beneficial for the ecosystem, but a very wide range of carefully balanced life forms in a resilient, complex and difficult to parse network that makes for a healthy forest. Some fungi destroy healthy trees. Some fungi connect trees of the same species and some the trees of different species. Most bacteria are important links in a long chain of nutritional custody. Some are incredibly harmful and only kept in check by a specific fungus. Some insects are in balance with the life-cycles of the trees they feed on and others are wildly out of sync with current growth cycles and climate changes and simply destroy. Perhaps the most compelling conclusion of this narrative is that we don’t know enough to understand what is actually happening, much less enough to interfere with it.

Simard concludes that all of the natural world is interconnected and her conclusion is particularly poignant as she points out that the hard-won insight of her decades of research is nothing more than a “scientific” stamp of approval on the wisdom of both ancient indigenous practices and 19th and early 20th century logging and harvesting practices. The peculiar myopia of scientific “objectivity” had led policy makers to assume that forests could and should be “weeded” like a lawn, ignoring the ways that monoculture demanded constant intensive care that was barely sustainable for crops like corn and grass, much less hundred-year crops like Douglas fir and ponderosa pine. The “free to grow” policy that mandated destruction of all other plants in forest replantings, besides being deceptively named, was based on the first few months of improved growth and not on studies long enough to demonstrate long-term net negative effects. Simard’s efforts to get the policy changed required many more years of research, more numerous studies, and more carefully parsed data to overturn the ill-conceived method.

Simard does not address the obvious incoherence of studying interdependence and kin relationships among trees while living a nine-hour drive from her husband, children, and extended family. The horrors of the academic job market are too obvious to rehearse here, but the connection between her weekday isolation and the plastic barriers she erects around fir trees to demonstrate the trauma of being separated from the surrounding root networks and mycorrhizal fungi, seems so evident that I can only imagine she deliberately refused to include it. She does describe the weariness of the late-night drives, and the fraying of her marriage, but she merely repeats a platitude about her daughters being better off if mom and dad are separate and happier to be so. The divorce does not change her weekly commute, though, and she does not discuss what actually changes.

The final quarter of Finding the Mother Tree is poignant. More than her struggles to be taken seriously and more than the tension of her academic work and family life, Suzanne Simard’s struggle with cancer narrated alongside her struggle to understand and communicate the importance of ancient trees to the forest, is profound and moving. Driven by her own sense of mortality and by her desire to understand how her illness is affecting her daughters, Simard drives herself to better understand how large old trees sustain the forest ecosystem. Calling them “Mother Trees” out of an anthropomorphic identification with mothering as nurturing (another contradiction she does not address is how her daughters’ father was their primary caregiver for most of their childhood and how most trees fill both the seed-bearing and seed-fertilizing functions), she designs experiments with her graduate students to measure Mother Trees’ preference for kin in passing nutrients.

A series of different experiments confirms that this preference exists and is strong enough to give genetically related trees an advantage even though unrelated trees are also nurtured within the root and fungi network. The final piece of the puzzle, and the one that corresponds with Simard’s chemotherapy treatments, is the way that a dying tree sends its nutrients to the other trees to which it is connected. A mature tree that dies does not just send its stored carbon back into the soil via decomposition, although much of a fallen tree does just that. Instead, once attacked by insects or damaged by a storm, or clipped in a lab experiment, a Mother Tree actually forces nutrients out through its root/fungi network into other connected trees, leaving a bit more to its descendants but also sharing the valuable resources in a way that preserves the health of the entire forest system.

While Simard is still continuing her work, she also writes about passing the legacy of her work on to the next generation, both for her children and for her graduate students. Her hopeful notes about resiliency and the potential for dramatic improvement in management practices balance her dire accounts of beetle-destroyed forests and other damage driven by climate change. And, while not every tension is resolved in her narrative, Simard offers a balanced anthropomorphism that acknowledges that our understanding is limited by our metaphors but that some metaphors (mother, nursery, web, communication) will be more helpful in directing us to appreciate the complexity of the mysterious forest while others (weeding, plantation, competitor species) will tend to lead us into hubris. Simard’s book is less folksy and yet more personal than Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees. Its wealth of research detail and its investigative drive root it in reality while still offering the imagination room for exploration.

I grew up in the forest. As a child, an adolescent and young adult, I preferred being in the forest to any other place. I mused in the beech bottoms created by the upland creeks. I wondered at the towering white oaks and cow oaks which grew at the edges of the delta. I listened to the “whispering” pines growing on the ridges, mostly longleaf.

My focus in 4-H and in FFA was forestry. My father and I had a small tree farm. I went to forestry camp and did timber cruising as a young adult.

I hunted, fished, hiked, camped, and foraged in the forest; yet, my awe rested on the mystery of the forest. That awe intensified when I hiked the forest of Austria and Germany during my thirteen years in Middle Europe. It is only later, however, after returning to Louisiana, my home, that I discovered Peter Wohlleben and his work with the forest, not in its Gehalt but in its Gestalt. Each birthday, I ask for one of his books which I am linking to this post. He seems to be the German Suzanne Simard.

https://www.wohllebens-waldakademie.de/buecher

Comments are closed.