Saint Louis, MO. Of all the things pressing on me right now, the death of Norm Macdonald shouldn’t be one. I have 50 hours a week of consulting work, a class to prepare, elderly parents to tend.

But I spent yesterday afternoon lying on my couch listening to Nick Cave records, drinking Goose Island IPA—it isn’t bad, isn’t great. Warm St. Louis early evening, a palpable feeling of vague-mindedness, and at some point, I could feel tears streaming down my face. This is what happens to German men. We’re so accustomed to keeping our emotions in check that they often appear unbidden.

So, the death of Norm Macdonald. He was 61. I feel the way I felt when Philip Seymour Hoffman died, or Mitch Hedberg, Daniel Dumile (MF Doom), David Berman, Phil Hartman. David Foster Wallace. Like some great underlying force just…ceased. Shakespeare wrote, “Out, out, brief candle.” These guys were more like houses on fire in terms of their cultural presence. So was Michael K. Williams. David Berman. And my God, my mentor, my house on fire Hal Bush died a few weeks ago. And tomorrow we’re headed to a funeral in California; my wife’s dearest friend’s younger brother died in a car accident. I mean, all Thursday he was alive, but Thursday night he lost control of his F-150 and crashed into a tree. He was 38.

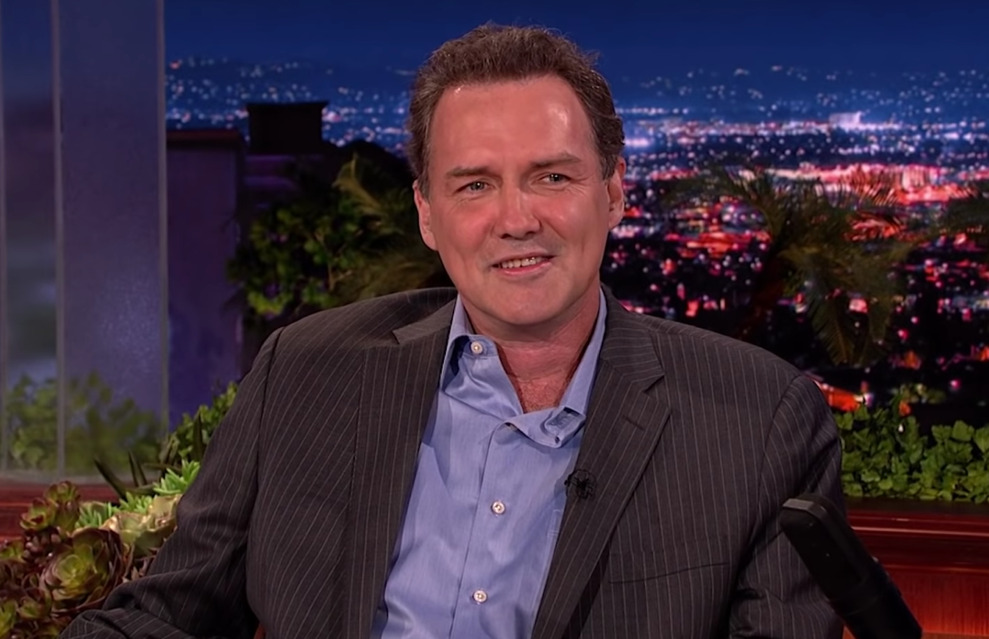

Norm Macdonald’s comedy was divisive. Some people find it, well, as my wife says, “not funny.” He was kind of like Andy Kaufman in that the joke was his whole presence. He was also kind of like a Canadian corn farmer, just telling stories that came to mind, no matter how long or leisurely, not concerned that he might have some facts wrong. His genius was in his manner of telling. Which for Norm meant plenty of pauses for knowing looks—smirks—as though the listener were in on the joke. His monotonous voice. Like we all know where this is going, right? But we didn’t know, and so his laid-back telling engendered a dramatic irony. Inverted dramatic irony: The player seems to know something the audience doesn’t.

Norm’s stock and trade was a variety of what Mark Twain referred to as “the humorous story.” To define this, Twain relies on a dichotomy:

There are several kinds of stories, but only one difficult kind—the humorous. I will talk mainly about that one. The humorous story is American, the comic story is English, the witty story is French. The humorous story depends for its effect upon the manner of the telling; the comic story and the witty story upon the matter.

The humorous story may be spun out to great length, and may wander around as much as it pleases, and arrive nowhere in particular; but the comic and witty stories must be brief and end with a point. The humorous story bubbles gently along, the others burst.

Anyone familiar with the lengthy “jokes” Norm told on Letterman or Conan recognizes that Twain is describing his method. Because the “humorous story” is a performance, Twain writes, it “is strictly a work of art—high and delicate art—and only an artist can tell it; but no art is necessary in telling the comic and the witty story; anybody can do it.”

Norm’s famous moth joke on Conan begins with some off-frequency comedy, if you can even call it comedy, such as, “My strongest material comes from real life. Like for instance today I was driving a car—you were kind enough to send a car to bring this ol’ chunk of coal here to the studio.” He gestures to himself, and the reference is lost on me. Chunk of coal? Rational Conan—caffeinated show-host diva Conan—says, “What do you mean, you get material that way? You get in the car, and what happens?”

Norm: So I get in the car, and my driver tells me a joke.

Conan: The driver we sent to pick you up told you a joke.

Norm: Yeah.

Conan: And you’re gonna tell it now on the show?

Norm: Yeah, that’s how I get my material.

Conan acts shocked, the audience is giggling, but in strict comedy analysis terms there is a lot up in the air. Are Conan and Norm on the same frequency here? Is Norm sort of, well, pranking Conan? What we’re witnessing is more like the first small movements of a complex ballet of gesture, statement, host/guest relationship, audience expectation, and a somewhat inscrutable character in the middle of it: the storyteller. His face indicates he has something meaningful to say:

So he tells this long story about a moth visiting a podiatrist and laying out all his life problems, and of course the premise and story are both riddled with contradictions right from the start. This is a story that doesn’t make sense, and it becomes even more absurd when the names of characters start showing up: Gregory Olinavich. Alexandria. Gregario Ivanilitovich. And his wife, “Some old woman I used to love.” The moth, were it not for his cowardice, explains Norm, would like to make use of the loaded pistol on his nightstand. We’re only two minutes in, and evidently we’ve wandered into a Kafkaesque nightmare, and Conan playfully interrupts:

“How long was this drive? What, do you live in the Valley??” Conan leans to the audience to collect applause. Norm barely acknowledges this except to pause until he’s invited to resume: “He says, ‘Doc, sometimes I feel like a spider, even though I’m a moth, just barely hanging on to my web with an everlasting fire underneath me.” We’ve moved from Russian existentialism to Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

I won’t give away the punchline, but there is, in fact, a die-cast punchline. Here’s where we move from standup to Twain’s “high and delicate art.” The punchline is not the point of Norm’s moth story, even though Conan plays the eager show host who can see it only that way. Conan manufactures a laugh and then waves broadly to the audience: “My congratulations to anyone who stuck it through to the end.”

“The end.” The audience had wanted or at least expected a joke, and Conan’s brilliant counterpoint reinforces this expectation. The fans had been waiting for the payoff—the prize in the bottom of the Cracker Jack box—the punch line. Twain calls this element of humor “the nub,” and the humorous storyteller’s objective is to “slur the nub”:

The humorous story is told gravely; the teller does his best to conceal the fact that he even dimly suspects that there is anything funny about it … Very often, of course, the rambling and disjointed humorous story finishes with a nub, point, snapper, or whatever you like to call it. Then the listener must be alert, for in many cases the teller will divert attention from that nub by dropping it in a carefully casual and indifferent way, with the pretense that he does not know it is a nub.

Norm doesn’t deliver his punchline offhandedly, but the “joke” still fails by most traditional measures. The audience expects a “comic story” with a clear point. Conan plays up that angle, embodying the other side of Twain’s dichotomy:

The teller of the comic story does not slur the nub; he shouts it at you—every time. And when he prints it … he italicizes it, puts some whooping exclamation-points after it, and sometimes explains it in a parenthesis. All of which is very depressing, and makes one want to renounce joking and lead a better life.

Very depressing indeed. Macdonald’s refusal to settle for such jokes is by design. Great artists push us and expose us the way Norm exposes his audience’s interpretive grid as being primarily transactional rather than relational. Conan plays his part as a typical show host, his half of a gag the two comedians had been running for decades.*

Another version of this exposure is Norm Macdonald’s crass joking. I mean, it’s not just crass; it’s unacceptable, maybe immoral. Don’t Google “Norm Macdonald” and “Who Writes These Jokes” because you will hate what you find.

Part of Norm’s later shtick was to ask visiting celebrities to read jokes they hadn’t pre-read. Each joke had some flavor of extremely misogynistic, racist, homophobic, or other hateful content in it, and its reader was stuck reading it until the most offensive part was reached, and then sometimes—often—the reader would become outraged. Bob Einstein went on a seemingly authentic rant against Norm for making him read such jokes. “Do you know we’re on the air? Do you realize this is your career?” So the joke was really on the guest with Norm playing the prankster puppeteer.

There’s a kind of death-in-life at work throughout Norm’s oeuvre. I haven’t even mentioned the Bob Saget roast for which he is perhaps best known, the one at which he was introduced, “Please welcome the incoherent Norm Macdonald!” Where other comedians brought comedy, Norm brought jokebook jokes—Vaudeville style send-ups that weren’t even funny. “People say you’re over the hill, but don’t believe them. You’ll never be over the hill—not in the car you drive!” Nobody laughed.

The death of comedy, the end of the joke. Norm Macdonald’s Bob Saget roast takes its place in the pantheon because it so effectively exposes celebrity roasting simply by inverting it. Norm ventures into bad joke territory so brazenly that he himself ultimately becomes the joke. You want a comedian? Here you go. Have it.

Since learning the news of Norm’s death, I’ve been imagining him in his very first standup appearances—trudging monotonously through a set, waiting for laughs, getting some, not getting others, and finally thinking, This is BS. And then expanding and maturing into a truly great comic. This is what you want? I’ll die on stage a thousand times before I die.

In a 2018 Vulture interview, he says, “You know, I think about my deathbed a lot.”

Vulture: What do you think about it?

Norm: I think I never should have purchased a deathbed in the first place.

We now know that he had been fighting cancer for years at that point. He knew what was coming—a terrible punchline to a lifelong joke. Not funny at all, really. The point is the meandering story, not the nub.

But when it comes to death, there’s no “slurring the nub.” It is what it is, as they say. As great comedy requires embodiment, its antithesis means disembodiment. So as I watch my dear mentor, watch our friend’s brother, witness an entire Mount Olympus of culture makers go body after body into the ground, I weep fresh tears not because I was so close to Norm Macdonald. I wasn’t. But because I know that this is about all we can do as mortal humans, and may God bless those who don’t pass it off for a buck or two. That carpe diem maxim—whose modern equivalent, already passé, is YOLO—stands next to another Latin phrase, memento mori: “Remember, you will die.” This, according to Plato, is the basis of all philosophy:

I deem that the true disciple of philosophy is likely to be misunderstood by other men; they do not perceive that he is ever pursuing death and dying; and if this is true, why, having had the desire of death all his life long, should he repine at the arrival of that which he has been always pursuing and desiring?

There’s no way Norm Macdonald desired physical death, except perhaps in the most painful moments of his nine years of cancer. But what all these profound culture-makers have in common is death-mindedness, which gives them the ability to fully pursue their art, because they don’t pay as much mind to the fleeting: the money, the fame, the critical disapproval. The legacy of a death-minded creator can be incredibly life-giving to those of us preoccupied with transient concerns. Norm’s whole-life commitment to comedy gave him the power to transcend, the way Jim Carrey transcended in his 2016 Golden Globes speech.

These performances empower us to think clearly about our own lives, with the end in mind. To live more authentically as ourselves.

* Portions of this section have been revised to clarify the interactions between Macdonald and O’Brien.

“Chunk of Coal” refers to a song by Norm’s friend -the late country singer/songwriter Billy Joe Shaver. Also, Norm’s “moth joke” is part of his filibustering on talk shows to get through his segment(s).

“Don’t Google “Norm Macdonald” and “Who Writes These Jokes” because you will hate what you find.”

Oh no, a comedian told an offensive joke, someone find me a couch to collapse on…

I don’t know if Norm was a good person or not. He made me a laugh a lot, and it was never at some out group–always at either himself or some celebrity–so on the whole his contribution to society was infinitely better than nearly any other “comic” of the past quarter century. RIP.

“Oh no, a comedian told an offensive joke, someone find me a couch to collapse on…”

People’s tolerance for what they regard as offensive varies. Nothing wrong with disclaimers to that effect.

Had it not been for Norm McDonald, I never would’ve met Jacques de Gatineau, whose life served a youthful porpoise.

Aaron. Thank you for this piece. Of the many obits and essays which chronicle Norm’s life and passing, yours is undoubtedly the most thoughtful, near-complete reflection of the man.

Thank you for articulating everything that I could not. This is why Norm will be so missed. This is why I loved him.

Be well.

Comments are closed.