This essay is part of a mini symposium on the opportunities and challenges educators face in the wake of a year-and-a-half of COVID. You can view all the contributions here.

West Palm Beach, FL. The COVID-19 pandemic threw all kinds of things into disarray in spring of 2020, including education. At all levels, most schools disbanded their in-person classes and sent everyone home, to resume class online. At my university, we found out on a Friday that by Monday we weren’t going to be seeing each other in person for a while. That Thursday I had been in the cafeteria with colleagues, eating lunch and watching television as the entire sports world ground to a halt through the course of our meal. Over the weekend, we worried about toilet paper and how to move our classes online. Since then, we’ve learned to teach remotely, in person with distancing, and in-person and HyFlex at the same time. This semester, we are closer than ever to normal, but one thing about life these days is that everything always feels temporary.

There was, and is, much to dislike about how COVID has affected higher education. The experience of the last year and a half has clearly demonstrated the importance of in-person learning and traditional in-person learning at that, as shown in Jon Schaff’s essay about the importance of faces in teaching. But it would be a mistake to suggest that only bad came out of the COVID classroom. Faculty and students alike often improved their skills with technology, learned to be adaptive, and sometimes even benefited from having to re-evaluate assignments and learning styles. Some people discovered abilities or strengths in themselves that they had not previously realized.

Yet perhaps most interesting of all, and hopefully of lasting benefit, has been something altogether unexpected. I remember at one point in 2020, everyone was riffing on all of the “Love in the time of COVID” books and movies that people must be writing. I’m not sure how many of those projects came to fruition, but many students and teachers have found remarkable ways to practice a love for learning—and for learners—in the time of COVID.

The only way to teach well during COVID has been with care. Faculty have needed to be highly attentive to students. If you teach at a small school, you are used to noticing when students are missing, but you do not always regularly follow up. Now you have a pretty constant sense of the general health status of all of your students (HIPAA-friendly, but you know who is “too sick” for the classroom). You are also more aware of their personal struggles if a family member is sick or has become unemployed. When students went remote, we learned more about their home environments—who couldn’t go home, who didn’t have internet, who needed to take care of younger siblings. COVID forced us to be more aware of the health and wellness of our students, and keeping them engaged in the classroom could mean more engagement in their overall lives. We learned to be more proactive in caring for our students as people.

COVID has also made care more obviously central to being a good coworker. Faculty turned to staff and to each other in new ways for help with technology, for interpretation of school policies, for creative solutions to classroom changes and new assignment needs. As with the students, we became more aware of the health and economic issues facing our community. We were more responsive when anyone lost a job, when anyone was absent, or when a spouse was ill. Faculty also learned more about the roles of various staff members on campus and came to appreciate more the work that happens outside the classroom. We were all forced to seriously notice our people in a caring way. The only way for everyone and everything to function was with loving attentiveness to each other.

At the same time, the COVID era has highlighted areas in which care and love have been lacking. At some schools, administrators showed a stunning disregard for faculty health and interests. At many schools, staff were exposed to greater health and financial risks than faculty, without hesitation. In some places, students have been cavalier about the health risks faced by their instructors. This fall, at least one professor has retired mid-class when a student refused to wear a mask, despite requests and the advanced age of the faculty member. Many schools made hard budgetary decisions in the past year and a half. Some implemented those decisions with compassion, others acted very callously. The lack of care at some institutions and with some policies has never been more noticeable.

COVID has shifted the conversation about education and about work in some profound ways. Very often op-eds note this reality and then talk about the “remote” question, but another question has actually been quite central: how do we best love our neighbors? Due to the craziness of COVID, all kinds of people are seriously considering how love of neighbor should affect university and educational policy. We are suddenly caring about caring, not as a peripheral subject but as central to the mission. That is shocking and amazing.

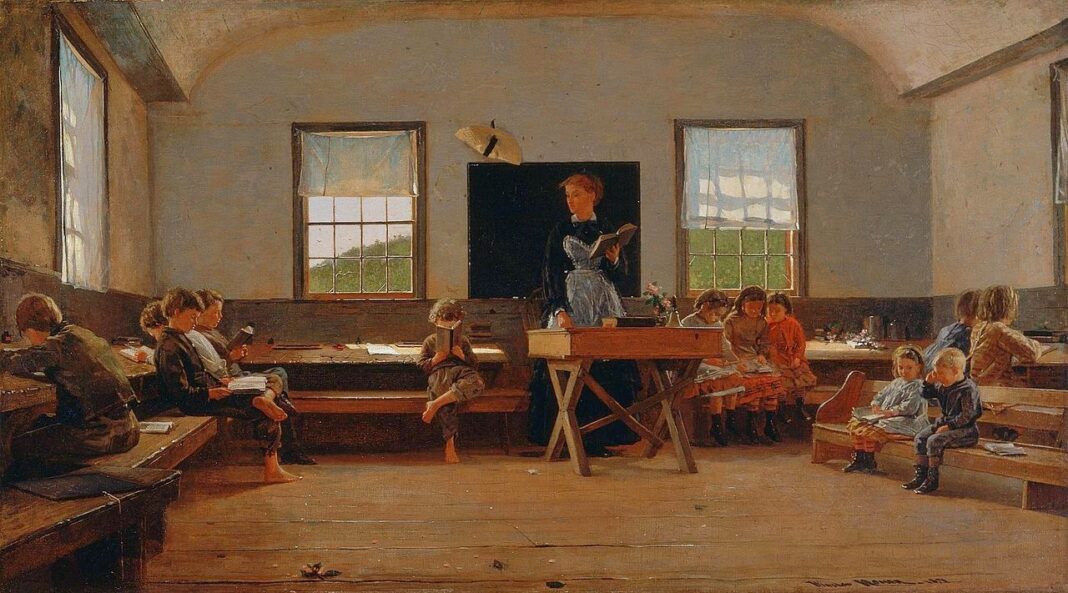

The centrality of care in a good educational institution is not just about an accommodating environment or a softer, gentler “safe space.” In truth, care has long been central to good educational institutions, even if it goes unmentioned when policies are crafted and decisions are made. How many people today are in job fields because of the caring influence of a single teacher in their youth? How important is love in motivating learning?

As always, Tolstoy speaks to this issue. In Anna Karenina, Part V, Chapter 27, Anna’s son Seryozha is struggling academically, and the reasons are not at all obvious to his guardians:

Both his father and his teacher were dissatisfied with him, and it was true that he was a very poor pupil. But there was no way it could be said that he was a slow-witted boy. On the contrary, he was far more quick-witted than those boys his teacher held up as an example to him. It was his father’s view that he did not want to learn what he was taught. But the truth was that he could not learn it. The reason he could not was because there were demands in his heart which were more pressing than those made by his father and his teacher. These demands conflicted with each other, and so he was locked in a struggle with those educating him.

He was nine years old; he was a child; but he knew his own soul, it was precious to him, he protected it as the eyelid protects the eye, and he let no one into his soul without the key of love. His teachers complained that he did not want to learn, but his soul was filled with an abundant thirst for knowledge. He learned from Kapitonich, from his nanny, from Nadenka, from Vasily Lukich, but not from his teachers. The water that his father and his teachers were expecting to turn the wheels of their mill had long ago leaked away and was working elsewhere.

COVID has managed to make love central to the conversation surrounding college education. The virus has given us many headaches, but it is also giving us an opportunity as we re-evaluate policies and practices and seek to care for one another and for our students. That is as it should be.