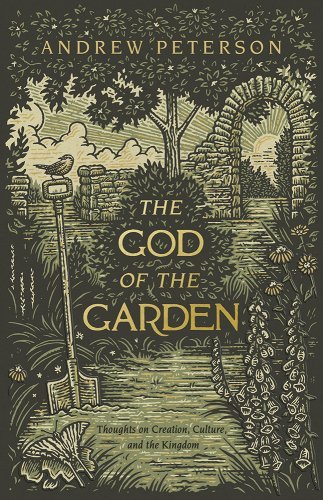

Baltimore, MD. Andrew Peterson wants you to appreciate just how wonderful trees are. So he wrote a book about them, entitled The God of the Garden: Thoughts on Creation, Culture, and the Kingdom. The point of the book is not exactly about trees, nor gardens (despite the title), nor green, growing things in general. The latter is a through line for the book, but “growing things are good” isn’t a sufficiently coherent claim for a book. And that is why the book ends up being rather disappointing.

Allow me to admit it all up front: I hate giving this book a negative review because I want to be Andrew Peterson’s friend and friends usually don’t give a lot of criticism upfront. I have loved his music and his Wingfeather Saga books for my entire adult life. I also hate giving this book a negative review because it’s a book that ably describes the shame and lies of being clinically depressed, and I don’t want a negative judgment to heap those feelings on another person. I have felt those same feelings, and Peterson’s music has been one of the things that has helped me hold on through very, very dark times.

Lastly, I hate giving this book a negative review because I think what Peterson is trying to say (in certain parts of the book) is a matter of critical importance and of great interest not just to FPR readers, but to just about anyone who listens to Peterson’s music or reads his other books. He describes the problems of American sprawl and callousness towards green spaces that is upstream from a great many woes in American culture and society, and he draws our attention to an alternative way of life in that is beautiful and compelling. But he does so in a way that always feels like he’s apologizing for being right, and no writer as good at telling the truth as Andrew Peterson should do that.

Going South Feels Like Going Downhill

The book opens with a description of the place Peterson lives and writes, followed by recollections of his boyhood in Illinois. Trees feature prominently in his memory, and he describes his adult search for one particular tree that his family used to go and sit under as they read or told stories, or prayed, or simply sat. The family moved to Florida when he was still a young boy, and there he recounts the beautiful garden that his friend’s father planted in memory of their deceased daughter.

Even in these early chapters, Peterson begins to mix in the themes of destruction, death, and sorrow that come to dominate the later parts of the book. He describes how some of the oldest trees in North America have been destroyed by carelessness, greed, or ambition, then meditates on how all of the hard work his parents have put into making their property beautiful may one day be erased by a future owner of that property in the way that his friend’s father’s garden was. He has more hope for the trees he has planted at his homestead enduring to his own grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but there is still a fragility to tended green spaces that unsettles the reader through these early chapters.

The narrative then starts to jump around chronologically, which becomes frustrating. Peterson’s journey from a city apartment to his current homestead comes first, followed by a chapter about his tour of the UK disrupted by COVID, followed by a chapter about his troubled teenage years, followed by a chapter about one of the darkest lows in his depression in his early 40s. This could have worked if there was some kind of thematic organization to the book, but that’s not really present, either. The stories themselves are poignant with longing, regret, despair, hope, and love—but they simply don’t work as a unit.

The strongest chapter is the one where Peterson recounts his teenage years. A pastor’s kid who moved at a tender age, he always felt out of place in the Deep South and judged his peers harshly for some of their cultural affinities while he disappeared into the world of fantasy novels and Journey albums. He was lonely, angry, and mourning the loss of his innocence all along; it wasn’t until he read The Yearling as an adult and saw himself in the main character that he was able to see all of the good things that his younger self pushed away. He captured this process of recollecting was in Light for the Lost Boy, arguably Peterson’s best album, and the stories he tells in the book flesh out themes that the album explores in a rich way.

Many of These Trees Were My Friends

From there, the book leaves its focus on Peterson’s life (except for a chapter about his encounter with the story of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane) and moves more to reflections about place and preservation. Peterson’s journeys to the UK and Scandinavia feature heavily here, as he feels that the English tradition of public footpaths has created a much healthier respect for trees, gardens, and fields than is present in the US. He mourns the unending suburban sprawl, the interchangeable strip malls, the paved-over Native American burial grounds, and most importantly the disconnection between a place and its people that hinders both from truly appreciating what is good about one another.

Here, unfortunately, is where the wheels really come off. Peterson is able to perceive that much of the American landscape runs contrary to the way things ought to be and that our collective choices to build our infrastructure around cars rather than people have been disastrous. But like a boxer who is more showbiz than slugger, he spends all of his time dancing around without ever throwing a punch. It almost feels like he is too afraid of stepping on anyone’s toes to take his opportunity to connect a solid left hook.

It’s clear that Peterson understands his subject well enough; he cites Jane Jacobs and James Kunstler as he works through his thoughts, and he’s read enough Wendell Berry to know just how unsettled America is. Our “no-places” full of empty parking spots and chain stores selling stuff we don’t need are vilified more than once. But his final plea is hardly more than encouraging his readers to stop and smell the roses, tacking on a brief note that “[i]nfrastructure, city planning, creation care, justice, neighborliness, and stewardship of resources are all theological concerns.” This is a sentence that belongs in an introduction—and one that merits further development.

Peterson mentions more than once that he can see 86 acres from his cabin that seem destined for a subdivision, and he’s already mourning that eventuality. While learning to appreciate the beauty and goodness of trees is a crucial step in reclaiming God’s creation for what it was meant for, it’s hard to imagine anyone who would pick up this book that doesn’t already agree, and it’s hard to imagine a skeptical person who happens to read this book being challenged by any of the thoughts it contains.

The God of the Garden wasn’t and shouldn’t have been a policy white paper. It merely should have connected the dots between the lost little boy who hated his small town and our lost nation of men and women who built our roads, highways, and subdivisions in a way that divorces us from nature. It should have said, in no uncertain terms, that the only way to make things better for America is for America’s citizens to collectively commit to living and building in ways that are more sustainable and keep us more closely in touch with the Earth and its creatures. It should have kept the pre-Entmoot Treebeard, full of caution about being too hasty, but still given us a little more of the post-Entmoot Treebeard, ready to storm Isengard.

Not Altogether on Anybody’s Side

The challenge of making such statements or implying that someone else should have made them is that the America we all live in offers very few opportunities to simply undo generations of car-centric, consumerist madness. Peterson, who has made a great deal of his living traveling by highways from one commuter-oriented megachurch to another, understands this as well as academics who must move to wherever they can find a job, missionaries who fly back and forth across oceans, or farmers who sell their bespoke grains online to yuppies. The good people at Strong Towns, New Urbanism, and this very publication work hard to figure out the means and methods of changing our situation, but it’s not like we can just blow up Orthanc and be done with it. Perhaps this is part of Peterson’s reticence in the book to make any bolder claims or push for more drastic action.

Another story from earlier in the book gives us a glimpse into the challenges America faces and how things could be different. Shortly after graduating from college, Peterson and his wife lived in the city of Nashville, in a neighborhood marked by violence and poverty. He describes their efforts to love the children in their neighborhood, even to the extent that their church would send a bus to bring all the kids in their little apartment Bible study to church. But then a drive-by shooting occurs on their block, followed by a neighborhood burglary of Grinch-level proportions (even their wall phone is stolen). At that point, Peterson and his family move out, ending their relationships with those kids.

It’s a tough story to read, and by his own account Peterson is still “conflicted” about his decision. Having chosen to live in a similar neighborhood myself for years, I can say that not moving out doesn’t lessen how conflicted one feels about one’s life and ministry there. But these neighborhoods are, I think, the best chances that Americans in general and Christians in particular have to reclaim what our structural inequalities, racism, and disregard for the built environment have wrought. Community land trusts can be formed, vacant lots and vacant houses can be turned into gardens or meadows, and churches that have the trust of the community can be vehicles by which people who are suffering and broken can find a path to wholeness.

The questions and problems that Andrew Peterson raises in The God of the Garden are thorny and complex, much like his own clumsily interwoven personal narrative. For those who love Peterson’s music, you will find in the book biographical stories that illuminate some of his best songs and spell out a theological narrative of hope and redemption that heretofore has mostly been in songs and novels. His thoughts about why Americans don’t care for the good things that grow up around us (and how we could make our places what they ought to be) deserve greater development. Perhaps he’ll write a novel or an album about the subject—knowing how good Peterson is, I would certainly not hesitate to pick either up.

And if you’ve never read The Wingfeather Saga or listened to his music, don’t let this review put you off of either—I still heartily recommend both and will be playing Light for the Lost Boy when I feel overwhelmed by the darkness for years to come.