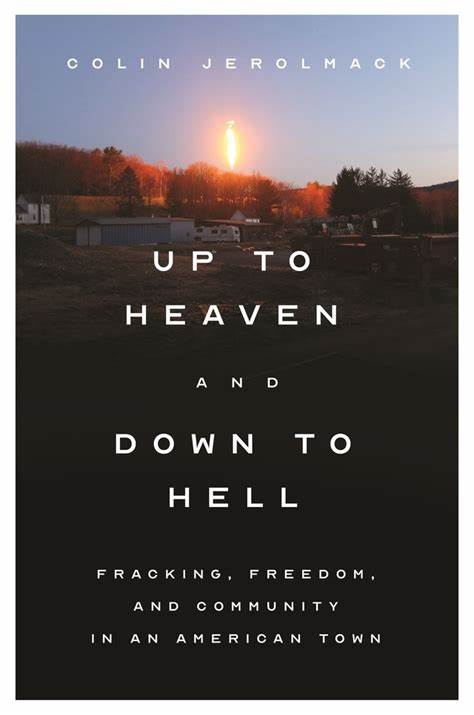

Grove City, PA. When I first held Colin Jerolmack’s book Up to Heaven and Down to Hell, I puzzled over the cover image: a dusky photograph with a few homes, sheds, and a trailer in the foreground and a giant plume of fire emerging over treetops at the edge of the woods. Why would someone think this was a good photo, let alone a strong image for a book cover?

Looking at the cover next to me, my husband immediately recognized the fire: a gas flare. “It burns off the impurities in the gas,” he said. “And it’s as loud as a jet engine.” Looking back at the image, I wondered if the distance between the flare and the photographer that led to this mediocre photo was to protect the photographer’s hearing. I also felt for the residents of those homes in the foreground of the photo. The racket they must have endured.

Distance, both physical and cultural, is something Jerolmack tries to bridge in Up to Heaven and Down to Hell, his cultural study of the impacts of extracting natural gas through hydraulic fracturing — known commonly as fracking — on Williamsport, Pa. and its surrounding communities. There’s distance between the residents who trace their lineage on the land back several generations and rusticators who retired from Williamsport or Philadelphia to rural estates in Lycoming County. And there’s the distance between anti-fracking activists (“fractivists”) who swoop in from out of town and longtime residents who can profit by becoming lessors.

But Jerolmack’s journey began when he sensed another distance: that between himself, a New York University professor of sociology and environmental studies, and the people who agreed to lease their land to energy companies. As his environmental studies students learned about fracking, they decried the practice and the lessors and wanted to attend an anti-fracking rally. Jerolmack asked his class of 80 students if they knew anyone who had leased their land to an energy company. They didn’t. Neither did he.

“I realized that this reality spoke to the political and cultural distance between rural and urban America,” he writes. “And I worried that my students and I were enveloped in a cosmopolitan ‘filter bubble’ that isolated us from information and viewpoints that might tell us a different story about fracking.”

So Jerolmack moved to Williamsport for eight months in 2013 to watch the issue unfold at the local level and meet the actors in the environmental drama: land men who worked for gas companies and sold residents on the glories of leasing, residents who signed the leases, local legislators who sincerely believed fracking was a win-win for the community, and advocates for responsible fracking.

I expected Up to Heaven and Down to Hell to be a kind of city mouse/country mouse tale. To be sure, Jerolmack discovered people who lived very differently than him, but he’s not interested in caricatures. His empathy and respect for them are clear, and he wants to bring readers as close to the issue as possible; it’s in this spirit that he brought a lessor to New York City to meet his students.

Ever the educator, Jerolmack breaks up his portraits of fracking lessors with mini lectures in political and social theory regarding thinkers from Tocqueville and Locke to more obscure contemporary scholars. As he explains, the United States is the only country in the world where an individual’s property rights extend “up to heaven and down to hell,” and the overwhelming majority of gas wells in the US are on private land.

Largely absent from the discussion was the economic impact of the larger fracking industry. Jerolmak asserts that most of the drilling jobs went to workers from Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado who traveled to rigs. And research shows that the gas industry overstated how many local jobs it would provide.

That might be true, but a whole industry sprang up to provide gas companies with the resources they needed, and many of these employees were local to drill sites. Between 2007 and 2014 drilling brought 21,000 jobs to Pennsylvania, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Drilling brought jobs to communities hard hit by deindustrialization, and it brought them at a time when the country was clawing its way out of The Great Recession.

And that is how fracking found its way into my life. My husband was one of the locals hired not to drill, but to work for a company providing housing and office accommodations to the workers on the well pad. For his first three months on the job in 2012 he worked just 30 miles west of Williamsport. He might have even visited some of the same sites Jerolmack frequented a year later.

It wasn’t the job my husband expected after finishing seminary, but with churches forced to freeze hiring when giving dried up, working in the natural gas industry was the first job he found in three years of searching that could comfortably support our family. And as the industry grew, he found fruitful opportunities for professional advancement and development.

For the residents that Jerolmack spent time with around Williamsport, the consequences of fracking were not always so rosy. Certainly the royalty checks improved life for many. New pickup trucks and roofs on the barns were the telltale signs that gas money was flowing into communities. But the industry overwhelmed everything else in their lives, just as the gas flare overwhelms the book cover.

In Pennsylvania, the state took away the local municipality’s say in whether and how fracking could take place in a township. Townships could hold public hearings, but they were powerless to deny a drilling permit. As a result, leasing became a private transaction between landowners and drilling companies. Jerolmack found a few residents who decided to band together as neighbors and collectively bargain with a drilling company, but many residents didn’t realize they had that option when the land man came knocking with an offer from the gas company.

And even if residents decided not to lease, they still had no say in what the neighbors decided and had to suffer the consequences, whether the din of a continuously-operated drill site or contaminated water from a faulty well casing. Jerolmack attended a township board of supervisors hearing wherein residents learned that during a proposed well’s construction phase, 150 to 300 big rigs would trundle the dangerous country roads each day for three to five months. One resident calculated that 18,000 to 20,000 trucks would rumble past his house during the construction phase. And though he objected at a municipal board of supervisors meeting, he was powerless to change the outcome.

One of the tensions Jerolmack explores is how the presence of outside activists impacted residents’ opinions of gas companies. Shortly before Jerolmack moved to Williamsport, Susan Sarandon and Sean and Yoko Ono had brought a busload of New York protesters into the rural areas around Williamsport to protest fracking (which Gov. Andrew Cuomo had banned in New York). Residents resented the publicity stunt. Even interference from an activist professor 45 miles away at Bloomsburg University raised the hackles of residents. What bothered residents the most, Jerolmack observed, was that the protesters didn’t even live in the community.

Locals who supported fracking seemed, to Jerolmack, less willing to speak up against the problems they saw fracking bringing to their communities for fear they would betray their neighbors and somehow align with fractivists. Even lessors who experienced permanent water contamination were hesitant to fight gas companies. In their eyes, being a good neighbor meant staying quiet for fear their complaints would attract outside agitators.

Many rural residents were suspicious of some who advocated for responsible drilling. Responsible drilling advocates were often Williamsport residents, and their meetings took place at tony Williamsport hotels rather than out in the rural communities where the drilling was taking place.

Bridging these distances more than anyone else was Ralph Kisberg, a Williamsport resident whom Jerolmack describes as holding a “(measured) anti-fracking stance.” Kisberg co-founded the Responsible Drilling Alliance because his years of working in offshore drilling taught him enough to worry that the drilling activity picking up around his hometown would endanger the landscapes of his childhood.

Kisberg knew all of the players in the drilling industry because he sought them out, built relationships with them, and worked to develop common ground among members of the Responsible Drilling Alliance and lessors who believed their decisions to lease were private matters. And Kisberg had some success in bringing the public’s attention to plans to drill around a beloved spot at a beautiful state park: due in part to his efforts, the gas companies put the plan on hold indefinitely.

One energy executive told Jerolmack, “If we had more people like Ralph out there trying to find collaborative solutions to energy development problems, the world would be a much better place!”

Though the rush to drill new gas wells in Pennsylvania has slowed considerably since 2014, companies are still adding new wells, even trying to drill them in state parks. And as more information emerges on the long-term environmental effects of fracking, it no longer appears to be the win-win path to energy independence once imagined.

Jerolmack’s time in Williamsport led him to view local solutions as the best path forward in handling fracking, with some power and say returning to the people who will also have to shoulder the consequences. Reading about the time he took to understand the issues on the ground made me more willing to consider his recommendations, even if I don’t plan to join a fracking picket line.

Like many of the residents Jerolmack met, I benefited from fracking’s boom in Pennsylvania. It gave my husband a job with good pay and nearly boundless growth opportunities at a time when the field in which he had hoped to find a job was not hiring anyone. And like lessors near Williamsport, we were impacted by the drop in oil prices when my husband’s job dried up. But he left with marketable skills and experiences that helped him land a better-than-we-could-have-dreamed job leading a nonprofit. It’s not gas industry pay, but I’ll take it.

I look back on his time in the natural gas industry with ambivalence—thankful for the well-paying job and leadership opportunities afforded my husband when it seemed that no one was hiring, but never forgetting the toll a job in a 24/7 industry took on our family.

Up to Heaven and Down to Hell traces a similar ambivalence in others whose lives have been affected by fracking. Jerolmack shows how royalty checks allowed residents to keep property that had been in their families for generations, but also disrupted and sometimes forever diminished their quality of life. For some, fracking was the beginning of the end for their social circles. Residents who came together to negotiate favorable lease terms moved away when the well contaminated their drinking water. Others began attending municipal hearings over future drill sites to offer their mixed experience with leasing, becoming low-key activists involved in municipal politics.

There aren’t easy answers to the problems fracking creates, and, like many industries, fracking generates losers and winners. But by spending time up close with the issues, Jerolmack models a good approach to complex problems: he bridges the gap between distant, often entrenched groups, listens carefully, and doesn’t insist on imposing a simplistic, one-size-fits-all solution. Would that more of us follow this model.

Ms. Fowler,

This is a great little essay about what looks like a great book, telling some great stories that need to be heard. I know a little about the local politics which have surrounded fracking by the gas industry over the past decade, but mostly just here in Kansas or next door in Oklahoma. Your review of Jerolmack’s book, which artfully communicates the theme of distance and ambivalence throughout, makes me want to learn more, so thank you!

In particular, I’d be interested to learn how Jerolmack assesses the Williamsport citizens who became, as you put it, “low-key activists involved in municipal politics,” especially given your observation that “In Pennsylvania, the state took away the local municipality’s say in whether and how fracking could take place in a township. Townships could hold public hearings, but they were powerless to deny a drilling permit. As a result, leasing became a private transaction between landowners and drilling companies.” The struggle of the people of towns and cities to push back against their states and assert greater local and democratic sovereignty over their municipal places has been a long-standing concern of mine, so I’m always looking for examples of where it has worked, and where it hasn’t.

Comments are closed.