Arroyo Seco, NM. Wes Jackson and I spent a good part of 2019-20 working on two books—Wes’ collection of stories titled Hogs Are Up: Stories of the Land, with Digressions and my The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability, which summarizes Wes’ key ideas over the past half-century.

While writing and editing, we talked on the phone almost every day, enjoying both the discussion of ideas and the swapping of stories. After the books were finished, we decided to capture those exchanges for “Podcast from the Prairie.” Like our phone conversations, the episodes are a mix of analysis and narrative. Wes’ ideas about human affairs and the larger living world come alive in the stories he tells, starting with his early life on a Kansas farm, through his academic work and teaching career, to his four decades of leadership in the sustainable agriculture movement at The Land Institute.

Here’s how I started each episode:

I’m Robert Jensen. I’ll be your guide into the restless and relentless mind of Wes Jackson. I first bumped into Wes’ work more than three decades ago, and his ideas have had a profound influence on my thinking about society and ecology. My conversations with Wes in this podcast will explore why that is and give you a chance to hear how his mind works, how Wes has cultivated the art of “seeing small and thinking big.” We’re going to have conversations about global issues that begin with Wes’ deep roots in the prairie, where he spent most of his life.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and concision, and in some places we have expanded on the ideas and made connections that we had missed in the flow of conversation.

“Podcast from the Prairie,” a project of Perennial Films in collaboration with the New Perennials Project and The Land Institute, was produced by Michael Johnson, Bob Sly, and Bill Vitek, with music and audio production by Marcelo Radulovich of Titicacaman Studios. All the episodes continue to be available online for listening on all the podcast platforms, including SoundCloud.

Episode 1 explained Wes’ “Intellectual Grounding.” Episode 2, “Respecting Your Tools,” focused on the importance of approaching work responsibly. In Episode 3, Wes talked about why he is “Mad About Science.” In Episode 4, we discussed the role of religion in modern society and why Wes says there is “Methodism to My Madness.” Episode 5, titled “The Portrait of an Artist as an Old Man,” explored the creativity of humans and the ecosphere. The final two episodes of the podcast’s first season focused on those two books—Episode 6 on Hogs Are Up: Stories of the Land, with Digressions and Episode 7 on The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability.

Conversation 1: Intellectual Grounding

Robert Jensen: I want to start with the key influences on your thinking, on how this restless and relentless mind of yours got formed. A blunt, and perhaps embarrassing, question to begin. You won a MacArthur Fellowship in 1992, which is commonly referred to as the “genius grant.” Mr. Jackson, are you now, or have you ever been, a genius?

Wes Jackson: [laughing] No. I have plenty of evidence that I am not a genius. For instance, I’ve had some statistics courses—you’ve got to have statistics if you’re going to be a geneticist—but I can’t derive equations. I can do what you might call cookbook statistics. Show me the equation and I’ll comply. Now, here’s a digression right off the bat. The story goes that the founder of modern statistics, Sir Ronald Fisher, apparently could just write down an equation and know it was right. Then he would get graduate students to derive them. He gave one equation to a student and told him to derive it, and the student kept coming back. “Sir Ronald, this is not going to work.” Sir Ronald said, “Yes, it will.” After months, maybe even a year, the student finally got it. Now, Sir Ronald probably was a genius. Those people are different than us. There are certain musicians who can play the piano just as soon as they put their fingers on it. People who can think fast have a sort of genius. I can’t think fast. I’m a ponderer. I’m a slow reader. I’m also beginning to think I have attention deficit disorder and always have. Anybody who thinks I’m a genius doesn’t know enough about geniushood.

RJ: Let’s go back to your early schooling. You grew up in North Topeka, Kansas, and went to public schools. What kind of student were you in grade school, junior high, high school?

WJ: I went to a two-room country school where the school year was only eight months long, because this was rural America and students were needed for farm labor during planting and harvest. We had some good teachers and some not so good. I had a very good teacher for the seventh and eighth grades, and so when I went to high school, man, I could hardly be stopped. But my sophomore, junior, senior years were terrible. It wasn’t until about halfway through my junior year in college that I was able to overcome all that. I had Ds. I had a lot of Cs and Bs, and I had As here and there. In college, I had a D in botany, and so I went to the prof and explained that I couldn’t have a D in my major field, which was biology. He said, “Well, you got one.” Then he said he would give me six weeks to study and give me another exam. “If you get an A on that, why then I’ll give you a C,” he said. I ended up getting a C for the course, and that same professor later wrote a glowing recommendation for me to get into graduate school in botany at the University of Kansas. So, it’s been sort of all over the place. I never checked, but I was probably about right in the middle of my class in both high school and college. My best experiences were in graduate school, because by that time I had learned what I was really interested in.

RJ: So, you’ve disavowed the genius label. You weren’t a child prodigy. You were an uneven student. But when something caught your fancy, you would dig in.

WJ: I guess one could say I was sort of in business for myself, and so I wasn’t worrying about grades. I either did it or didn’t, according to what was satisfying.

RJ: You did well enough to graduate from high school and get a biology degree from Kansas Wesleyan University. You did a master’s degree at the University of Kansas in botany. And then in the early 1960s, when genetics was really taking off as a field, you started a Ph.D. in genetics. What led you to genetics?

WJ: I think if you grow up on a farm, you can’t fail to be interested in heredity. You see the breeding of your cows or your hogs, and you knew the parents of those animals. You see all this diversity around you. Genetics just came naturally for me, probably because of the experience of growing up on a farm.

RJ: That’s an important point. We learn a lot about the world in places other than the classroom. What did you learn about the world on a farm, being born in 1936 during the Depression and growing up before the large-scale mechanization of the post-World War II period? I don’t mean specific skills you learned, but more about an orientation to the world and how to live in the world.

WJ: On the farm you have work to do that is directly connected to what you eat, as well as what you sell. You didn’t waste things. You didn’t throw things out. If you bought something in a container with a lid, that container would go to the shop to hold nails or screws. I remember there was a man who came around with a little scale in the back of his truck, and he wanted to know if you had any rags. My mother would pull out some rags that were too tattered to put together for any use. He would put those on the scale and say, “Well, that’ll be about a dime.” The rags went to him and we got the dime. I don’t know anybody today who goes around buying rags.

RJ: You’ve identified two things that are relevant from your farm experience. You were up close with the nonhuman world, with nature. You saw animals, you saw reproduction, and it made you curious about how the world works. And you also grew up in the Great Depression, and so that frugality shaped the way you lived.

WJ: What we used came mostly out of plant or animal material, like cotton, or some part of a hide. But now we have the chemical industry turning fossil fuel into cloth, and it’s a whole different world. In the world I lived in, you were caring for these products of the land. Now we have the products of the fossil fuels, and we’ve got more clothing around than we know what to do with. We’ve lost an awareness of source. Those fossil fuels come from somewhere, of course, from plants and animals that are millions and millions of years old. But we tend not to think about that.

RJ: In the introduction, I mentioned this phrase from a 2012 article about writing history by the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, “the ability to see small and think big,” which you’ve cited often. Gopnik says that good historical work cultivates the ability to see small—that is, pay attention to details—but to think big—in global terms with long time frames. It seems to me that you do that often. What was it about that phrase that grabbed your attention?

WJ: Anybody working in science ought to be seeing small and thinking big all the time. My friend Angus Wright, a Latin American historian, says we should always be toggling between the two levels. Focus in close to understand the details, he says, and then step back and look at the big picture. Some people only want to look at the small scale. Some people want to look only at the big and miss the small. I think if we’re left alone, we’re going to see both.

RJ: How well do universities today help people see big?

WJ: Like a lot of people, I worry about the emphasis on specialization. For years, the university has been pursuing an industrial ideal that focuses on production and efficiency. We got a knowledge factory that then got top heavy. My late friend Stan Rowe said the university had become a know-how institution, when it ought to be a know-why institution. That has a lot to do with people being encouraged to become the right kind of an expert in order to get a job. The culture has given high standing to the so-called hard-headed realist who just wants to know what something is going to mean in some direct economic terms.

RJ: Over the years you’ve said that we need to “drive knowledge out of its categories.” Is that what you were referring to, the problem of hyper-specialization in the modern university? What’s wrong with that specialization? After all, it has produced incredibly detailed knowledge about the natural world.

WJ: I think probably Wendell Berry is the one who gave me that line, which came as the result of us thinking about the university and the consequences of specialization that doesn’t come with a more expansive framework. The problem comes when people specialize without asking how all that knowledge relates to a key question: “What does it mean to be a human being?” There’s nothing wrong with learning the details, say, of how the atoms operate or what happened in a particular battle in the Civil War. But when categories of knowledge get too narrow they have a way of getting in the way of the larger social, cultural, political questions. That’s too bad, because when people are given a chance to think deeply about the human condition and where we seem to be headed, there generally is an openness to new ideas. People realize they need to be thinking both small and large. Then you can ask, what are the criteria for something being important?

RJ: Let’s go back to the moment you decided to start The Land Institute, back in 1976. You were a tenured professor at California State University, Sacramento, a full professor, which means you had pretty much guaranteed lifetime employment. You and your wife at the time, Dana Jackson, with three small children, decided to start The Land in Salina, Kansas, with little money and an idea for an alternative school that was not very well developed. What were you thinking? Why would you give up that security for a hardscrabble existence in central Kansas with no guarantees?

WJ: Teaching was my calling, and I wasn’t satisfied with the universities. I noticed that students were too often given to what I have called “minimal compliance,” when what I wanted out of them was “spontaneous elaboration.” So, what kind of an institution can move beyond minimal compliance? What will bring on the spontaneous elaboration? I thought that we might spend about half our time reading, thinking, and discussing, and about half our time in hands-on learning. I think about that opposable thumb and its role in building the brain, our ability to manipulate objects and to think. I believe the thumb and the brain are one, and if we don’t take the opportunity to use our bodies, then we are limited. I wanted a school like that. I had been impressed by Deep Springs College [one of the “work colleges” that combine study and labor] over there near the California-Nevada line. I think that the development of a healthy mind requires both study and work.

RJ: The Land Institute started as an alternative school, but quickly became known as a research institution, focused on what you call Natural Systems Agriculture—perennial grains grown in polycultures. Most of our grain crops, which are the bulk of our diets, are annual plants grown in monocultures, which has led to soil erosion and soil degradation. That’s a big idea, and probably what you are most well-known for. But you’re also an eclectic, even idiosyncratic, thinker. You talk often about how your ideas have developed in conversation with key friends. In this conversation, you’ve already mentioned several people: Angus Wright, one of your teaching colleagues in California; Stan Rowe, an ecologist you learned a lot from; the writer Wendell Berry. It reminds me of how you often say, “I don’t know what I think until I talk to my friends.” What’s so important about that interaction? Is it literally true, that you really don’t know what you think until you talk to your friends?

WJ: My late brother Elmer said to me once, “You’re always quoting somebody else—don’t you have a mind of your own.” The fact of the matter is that I don’t. No one really does, and if we did it would be a real mess. It’s kind of a big old soup, our thoughts mixed together. If my friends have an idea that is different than what I’ve been thinking, I want to take that seriously. You choose as friends the people you can rely on. I rely on some people who are just about the political opposite of me, and I don’t agree with everything they say. But I know that there’s a certain authenticity. They may have very good reasons for what they believe, and I want to know about that. I may get in some pretty good arguments with them, but many times those arguments will have been worthwhile, though not always.

RJ: You have had the pleasure of being around some of the experts in fields you care about. You’ve met Hans Jenny, one of the founders of the discipline of soil science in the United States. You also interact with people in Salina, whether it’s farmers or folks at the hardware store, and you seem just as interested in what’s on their minds as you might be about a well-known professor. What do you get from those day-to-day interactions?

WJ: There’s a certain amount of warmth and friendship, of course, even if the only time I see that person is when I go to that store. When you run into authenticity, into someone who is serious, you can learn something. One thing you learn is that everyone is dealing with problems. I remember thinking about that when I taught high school for two years.

When I started, I was fresh with a master’s degree in botany from the University of Kansas, and I was frustrated with these kids and was always talking about what they couldn’t seem to learn. Across the hall from me was the basketball coach, who had been there twelve years or so. One day he said to me, “Wes, you do not know what it was like when they walked out of their homes this morning. You do not know what problems they and their family members are going through. Ease up.” Well, I did and it was one of the best pieces of advice I’ve had. I can’t imagine how I was so full of myself at the time. I thought about that many years later during a conversation with Gary Snyder, the poet, when I still had too much sense of oughtness in me, which was fueling some complaint I had about someone. Gary said, “I think everybody’s doing about as good as they can.” Now, there are problems if you take that too far, but it’s worth thinking about, how the structure of a society is in some way part of what might be a deficiency in any one of us. So, when I’m in that hardware store, when I’m getting a piece of equipment for my tractor, and I talk with people whose worldview I disagree with, maybe even find to be dangerous, it’s important to think about where it comes from. What has that person been living with? There are a lot of times that when I get to know somebody and learn about their path, I’m surprised by how hard it has been for them.

RJ: In this conversation, you’ve used the term authenticity two or three times. What does that term mean to you?

WJ: Let’s take my plumber. I had to move my water well back 25 feet, because it has to be at least 50 feet away from the river according to the law. So, I needed to get a new well dug and casing put down and so on. The plumber knows his work and knows there are no shortcuts. He doesn’t try to do the job on the cheap, but he is interested in holding the costs for me to a reasonable level. He’s not going to dig down where he might just touch water. He’ll put it down to where there’s three feet of water over the intake. I can trust him because he has learned his trade and he knows what his work is worth. He’s authentic. Over the years I’ve been saying that the people who work out of pickups and panel trucks, the tradespeople, really are holding the world together. The plumber, the carpenter, the folks who know how to fix things, to keep things going. There’s something in them that I find trustable. They’re not going to lie to me when it comes to their craft, because they do not want to have to be called back because they did a poor job.

RJ: You’ve talked with the same kind of respect for scientists. Someone like Hans Jenny had mastered the craft of soil science, of figuring out soils. As far as I can tell, you don’t see a big distinction between somebody doing work in a scientific laboratory and somebody doing work on a plumbing fixture. The key is the respect for the craft and a willingness to do work well. Is that a fair summary?

WJ: Yes. It’s a matter of taking seriously their calling. I would say that taking our work seriously brings out an important part of our humanity. It’s part of an authentic life.

RJ: Do you think your attitude has something to do with growing up on the farm? You watched older brothers and sisters and your parents take their work seriously, on the farm and in the household. Is that where you picked up this respect for people who do their work well?

WJ: Yes, that’s part of it for sure. For instance, I’ve hoed a lot of bindweed, which is an awful weed with roots that go deep. If you attack certain weeds with your hoe and you leave some of that root, then it’s going to come back. You really have to stay after bindweed. And so you will find yourself bending over, grabbing that weed close to the ground and you pull it up, shake it, and you throw it behind you. Now, one of my great deficiencies is that I talk too much, and I used to talk too much during hoeing, and that means I would miss some of those weeds. When a brother dropped behind me to get a weed that I missed, I realized that I had been scolded without a word said. It was clear I had missed a weed and it also was clear to me that it was because I had been talking.

RJ: What were you usually talking about?

WJ: I can remember after World War II, as some of the folks came home, I was so curious about the war. Two of my brothers had been in the Pacific, but I could never get them to really talk about it. I will never forget one man who worked with us and had been in Germany, and I asked him something like, “Did you ever capture any German prisoners?” He said yes, once, maybe ten or twelve of them. I asked what happened. “Well, you know, we told them to run and then we shot ‘em.” They shot the prisoners in the back. So, I would have that on my mind. Something like that would change something in me and I would want to think about it. But at the same time the weeds have to come out. You stop at the end of that row and touch up your hoe to sharpen it and get back to work. There’s work you dare not neglect because it would just mean more work later when the weeds come back faster. I always thought that there was something wonderfully interesting that needed to be talked about, but you can be overly loquacious as a farmer, or a farm hand. I don’t know. There’s more to be said about all that, but I’ve already talked too much.

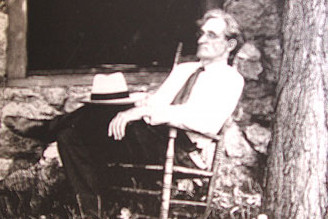

RJ: It sounds like you’ve always found it hard to keep still, but you did learn the importance of attention to detail, not only in work on the farm but also later in your academic work. Yet you never fully became an academic, leaving a university job to come back to the land. You have talked about how you still like working with your hands. Even these days, at age 84 as we record this, you’re still up on your tractor, out fixing things on the property, still working in your shop. Is that a conscious choice, to make sure you’re always using your hands?

WJ: It’s just what I want to do. I don’t want to go to the YMCA and lift weights. I don’t want to jog. But I’m happy to walk all over the place and be picking up things and lifting things and so on. One of the things I notice when I am writing at my desk for too long at one time is that I’ve got to get out, go do something that calls me. Right now, I’m cleaning up in the little red barn. There’s plenty of work there. It needed to be done and it’s good for my body. In the Upper Paleolithic, we didn’t go around lifting weights or dropping down to do pushups. We lived in a world that required us to use our bodies and our minds. Now, especially if we have a job that doesn’t call for much use of the body, we have to do all sorts of artificial things to compensate. I just don’t like that compensation routine. Some people like that, and I’m not criticizing them. I’m just more amazed that they have the kind of discipline to do it. I’ve tried to jog, but I would much rather take a long walk. And I would rather work up a sweat doing something that I consider real work.

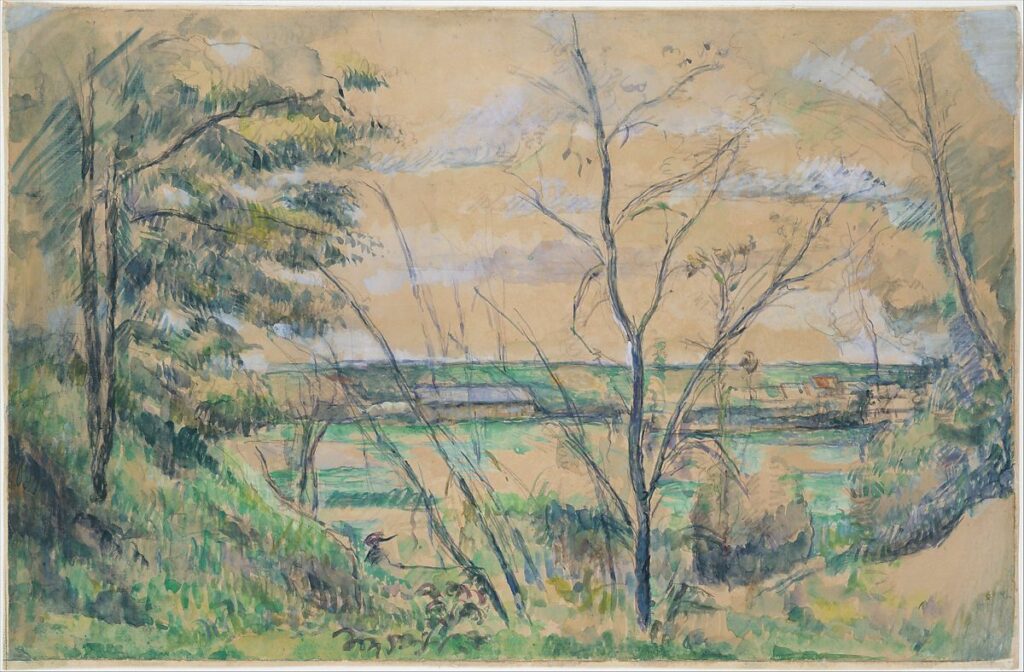

RJ: Your mention of long walks got me thinking about the role of landscapes in your life. You talk about the prairie with a lot of affection. When you’re walking a piece of prairie, what does that do to you? What are you looking for and looking at?

WJ: Oh boy. A lot of things, and I’ve wondered how much of it is a result of knowing the history of the prairie versus there being something intrinsic about it. There is a vegetative structure, a diversity of species out there. Beautiful flowering forbs, and the big bluestem, the little bluestem, the Indiangrass, the switchgrass, this beautiful ensemble. In Kansas, at least, that is a vegetative structure that’s been there through all interglacial periods of the Pleistocene, about 1.8 million years. And there are the insects, and the burrowing creatures that come up to loosen the soil. I had to learn about a lot of that history when I was in college. In high school or grade school, I didn’t know anything about a Pleistocene.

RJ: What about the appreciation of a landscape without the detailed knowledge?

WJ: I’ve wondered about that. I went to South Dakota the summer I turned 16, worked on a ranch of my mother’s cousin and her husband, Ina and Andrew Swan. And, boy, was that different than the hoeing. They had a hundred head of horses that roamed freely, and there were the prairie dogs, dens of rattlesnakes, and the original vegetative structure. There were farm ponds that they had bulldozed for the cattle to water, and they had stocked them with fish. It was a paradise. But I didn’t know the name of a single plant, and at that time I didn’t care. I’m amazed at how I allowed myself to be so ignorant. There is something that gets added once we know the names and learn the history, something that increases the voltage of interest, at least for me. Maybe that right there justifies education.

RJ: This reminds me of a trip we took, when you drove me around Kansas so that I could see your world. We moved out of farm country into the Flint Hills, which is mostly ranch land. And in the Flint Hills you couldn’t stop talking about the beauty of that landscape, which you had seen hundreds, maybe thousands, of times before that day. But coming upon them one more time, you still were taken by the beauty, and I commented on that. You borrowed a thought from Thoreau, that the world will always be more beautiful than useful. You’re a scientist, you deal with the very practical questions about agriculture, and yet this theme of beauty comes back so often in your life. Why is that?

WJ: Lots of people think first in terms of monetary value, but we can’t escape beauty. Let’s say a native prairie is plowed to create a grain farm. Some people count that as improving the land, meaning it is more economically valuable. The beauty of the unplowed prairie is gone, but I will still find the farm beautiful. Now, let’s say someone puts up a new housing subdivision on that farm land, increasing the value of an acre again. But even that doesn’t destroy all beauty. The beauty of the farm is gone, but could I find beauty in a subdivision that had formerly been prairie? Well, there are going to be sidewalks, and there are going to be cracks in the sidewalks, and there will be grass coming through, and I think that is beautiful. There will be insects, and if you pay attention to the insect you will see something beautiful. Or think about the geology. They will cut into the ground to make a road or dig a basement, and that cut might reveal geologic layers. At one point there was an ancient sea covering Kansas. And in the limestone, you may see some fossils from that sea, and there’s beauty there, too.

RJ: So, no matter how hard it seems people sometimes try to destroy landscapes, we cannot destroy the beauty of the world?

WJ: It’s hard to escape from beauty if you’re ready to observe the biotic activity and geologic history of the world. I’ve heard that prisoners who have a window, even if they all they can see is the same elm tree day after day, will say that’s what keeps them sane, and I don’t doubt it. Beauty is essential, and I’m saying that, even with the desecration of the ecosphere going on right now, it’s still there.

RJ: So, our appreciation of that beauty is tied up in how we perceive the world. We can learn to see beauty not only in pristine landscape or art museums but all around us.

WJ: That’s right. You can see beauty on the basketball court. I don’t watch much basketball myself, but I see it there, watching the human body that is so in command of itself. I was a track coach, and I will see it in a runner. I can even see beauty in those people who jog. They’re only thinking about getting their exercise, getting their two miles in or whatever, but it’s great to watch. You’re seeing something that comes right out of our past, out of the Upper Paleolithic, how we humans run. Now, there are some runners who are not as beautiful as others. Every now and then you see someone running a race and you hope they drop out. There’s just something about some bodies that doesn’t lend itself to running. But almost everyone looks graceful running, even some who are otherwise clumsy. Jim Ryun was the first high school student to break the four-minute mile, in Wichita. He was a beautiful runner, but I’ve watched him walk through a cafeteria and I was afraid he was going to drop his tray. We’re getting a little off the subject here about beauty, but I’m just saying that there’s so much to celebrate beyond mere utility.

RJ: I have one last question. You once said to me that you really don’t fit in anywhere. You grew up in a farm community and did a lot of farm work as a child, but you’re not really a farmer and never made a living as a farmer. You have a Ph.D. in genetics and you were a professor, but you’re not really at home in academic settings. You ran The Land Institute but you were hardly a typical nonprofit executive director. Is it fair to say that you’re a misfit? And if you are, has that been a good thing? Has it been an advantage?

WJ: I wouldn’t want to be a charlatan, which is to be a great pretender to knowledge. And I really don’t like the idea that I am something of a dilettante, which implies not going too deep into any one subject. But if being a dilettante is what’s necessary in order to have the great run that I have had in this life, then so be it. I’ve struggled to understand the meaning of the world and have had great friends to help me. The world presents so much for us to engage with that I find myself not getting too embedded in any one thing when there is all this diversity. So, I don’t know how to answer that. I do know that I was born into a good family and that helped.

RJ: What makes a good family?

WJ: Well, I never heard my father say he loved me, and I never heard my mother say that until she was about to die. I never had a sibling, except maybe a sister once, pretty close to the end of her life, say they loved me. But I knew I was loved and I felt loved. They also weren’t overly impressed with me being a college person or being a professor. About the most that they would say is, “I think Sharon’s doing all right.” [Wes’ full name is Sharon Wesley Jackson, and he went by Sharon until college.] My parents didn’t come to my graduation from college. They did happen to be there for my master’s degree, but they left just as soon as I got off the stage, because they had to get back home. It was thirty miles away and there was work to do the next morning. My father was born in 1886, my mother in 1894, and all of their parents were born before the Civil War. They came out of a world that was spare, and that carried over into the mid-1930s and the Depression, and then until their deaths. For a lot of the relatives and the neighbors, the world that unfolded with all this cheap energy, all the highly dense carbon, was a different world than they had known. I think of Milton’s line, “She, good Cateress, means her provision only to the good that live according to her sober laws and holy dictate of spare Temperance.” So, the good Cateress is nature, and in farming you get your provision if you operate according to the holy dictate of spare temperance. That was the world that I came out of. A lot of my activity since leaving home would have to be seen in the category of blasphemy of sorts, because I have not always lived according to the spare temperance, not even come close to the standards of that world. And that’s something to worry about.