“‘Aw, Partners, It’s Been a Bitch.’ A Letter from Ken Kesey After His Son’s Death.” Ken Kesey’s letter to Wendell Berry and other mutual friends describing the death and burial of his son is heartbreaking.

“Can You Go Home Again?” Bill Kauffman meditates on Gracy Olmstead’s Uprooted and the broader questions of place and responsibility that she raises.

“Theater Company Jettisons ‘Crushed-Velvet Shakespeare’ to Return the Bard to Populist Roots.” John W. Miller writes about the West Virginia “hicks who happen to know Shakespeare” and who are using their theatrical talents to “mak[e] an investment in [their] home.”

“Reality Minus.” It’s a bit rich for David Bentley Hart to note that someone else’s book is “a much, much longer book than it has any business being” and that its author fails to be “a concise expositor of ideas.” But Hart’s critique of David Chalmers’s arguments in Reality+—arguments that lead Chalmers to deem it sensible to want to “emigrate” from the physical world to some future virtual realm—is spot on: “To prefer the comfortable shelter of a simulated environment to the mysterious, wild, prodigal beauty and sublimity of life and mind — of psychē — that exist in vital nature, or even to be able calmly to contemplate absconding to the former in the aftermath of the latter’s eclipse, seems to me worse than pitiable.”

“Is There a Market for Saving Local News?” Clare Malone considers the growing spate of philanthropy-funded local news organizations. They have real potential, but as she points out, they tend not to serve America’s poor or rural communities.

“Dispatch from the Ottawa Front: Sloly is Telling You All He’s in Trouble. Who’s Listening?” What’s happening in Ottawa? It’s complicated, Matt Gurney reports:

Are there good, frustrated people just trying to be heard in the crowd? Yes. Are there bad people in the crowd, including some who’ve waved hate symbols and harassed or attacked others? Yes. Are there people taking careful care of the roads, sweeping up trash and shovelling ice and snow off the sidewalk? Yes. Are there hard men milling about, keeping a wary eye on anyone who seems out of place? Yes. Is it a place where some people are having good-natured fun? Yes. Is it a place some other people would rightly be afraid to go? Yes. And so on. But it’s even more complicated than it looks.

“Hawks Are Standing in the Way of a New Republican Party.” Sohrab Ahmari, Patrick Deneen and Gladden Pappin call for foreign policy restraint: “Conservatives must make a clear break with neo-neoconservative foreign policy and instead emphasize widely shared material development at home and cultural nonaggression abroad as the keys to U.S. security.”

“Rob Krier named 2022 Richard H. Driehaus Prize laureate; Wendell Berry wins 2022 Henry Hope Reed Award.” Mary Beth Zachariades reports on the latest hardware that Wendell Berry can add to his overflowing cabinet. (Recommended by Jason Peters.)

“The Maus That Roared.” Thomas P. Balazs pens a moving and refreshingly sane essay working through the issues around the recent controversy over Maus:

I’m a writer. I’m an English Professor. I’m a comic-book lover. I’m a Jew and a second-generation Holocaust survivor. I understand perfectly why Maus is great. It was important in my life. It helped me to understand my father, who was a lot like Spiegelman’s. That doesn’t mean I get to insist that every county in the country include the book in their eighth-grade Holocaust program. I don’t know the kids in McMinn County, but I doubt they’ll become Nazis because they didn’t get to read Maus until ninth grade. Nor will they become degenerates if they read it in seventh grade. But it’s not my call (or yours) unless you live in that county, and it’s certainly not antisemitic or book-burning to replace one Holocaust text with another. Even on International Holocaust Day. Even if it’s Maus.

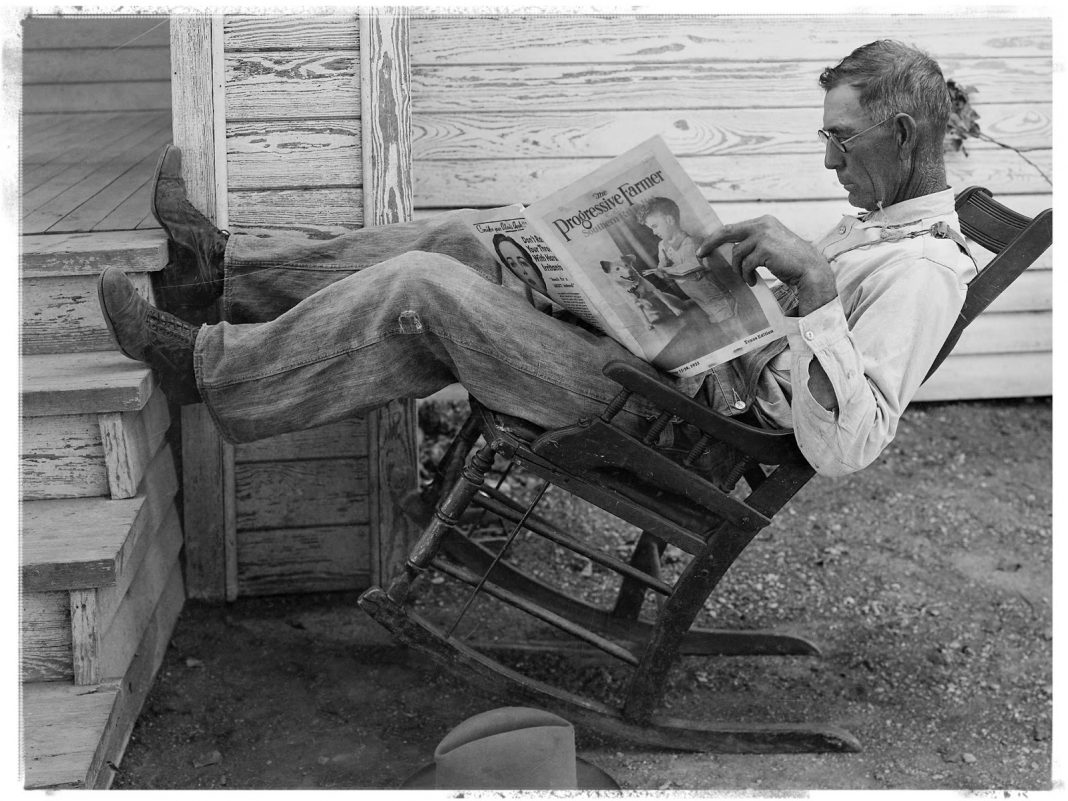

“How the Tractor Wars Pulled Us into Modernity.” Joseph Bottum reviews Tractor Wars: John Deere, Henry Ford, International Harvester, and the Birth of Modern Agriculture, by Neil Dahlstrom, and sets its story in the broader history of modernization and urbanization: “the widespread use of tractors on American farms came about through an odd set of trends and ideas — mostly unrelated and yet pushing in the same direction. The elective affinities that gave us the tractor may be small and unlikely, but they also form a useful figure, a synecdoche, for how the modern age happened.”

“Arise, Marasmius.” Noah Guthrie meditates on death, decomposition, and recomposition by pondering the mysteries of mushrooms: “Mushrooms are a bridge between worlds. You feed a stump, a mangle of bruised leaves, or perhaps a corpse to the mycelium, and out come bubbles of living color, a splatter-paint of cobalt and mauve and ochre. The fungus works like a mad chemist—deconstructing the dead into their basic elements, then rearranging them into newborn flesh.”

“Tilting at Windmills: The Threat of Christian Nationalism.” Mark David Hall examines how the term “Christian Nationalism” is defined and argues it is not nearly as prevalent as its critics assert: “Christian nationalism is an amorphous concept that is primarily used to tar Christians who are motivated by their faith to advocate for policies that critics don’t like.”

“At Lenin’s Tomb.” Eugene Vodolazkin contrasts a medieval understanding of time with the sense of time ushered in by the Communist revolution: “Modern historical consciousness takes for granted the idea of progress, whereby the present supersedes the past. In the Middle Ages, the present was seen as existing alongside the past: Both were under the eye of God, and so what really mattered was the link each event had with the heavens above, not with the immediate past or present.”

“Intellectual Freedom in Medieval Universities.” James Hankins looks at medieval universities and asks a telling question: “How did this amazing efflorescence of philosophy occur in an institution that, from our point of view, was so strict in regulating thought? And why were early universities so tolerant of non-Christian thought?”