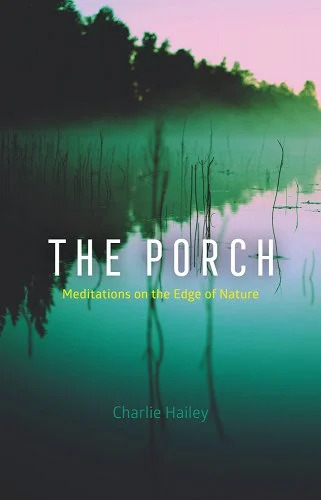

St. Augustine, FL. Architect and author Charlie Hailey’s new book, The Porch, opens with a scene describing a manatee, visible from the porch of his floating house on the Homosassa River in Florida. The Porch is grounded in that reality, but it is also grounded in metaphor. A porch is not just a great place to observe cypress and cormorant and manatee. For Hailey, a porch is both an architectural feature and a way of seeing and being in the world, even a “place to weigh the world.”

The Porch is a book about a particular porch and about the vantage points offered by all porches. It is organized into broadly thematic chapters: porch, tilt, air, screen, blue, acclimate. Hailey references Majorie Kinnan Rawlings’ “finely honed skills of reverie” in this book, and reverie also shapes his approach to writing. The Porch is full of observations, musings, and associations. Each of the chapters is loosely held together, allowing many subjects to come and go, not unlike the way a porch is able to breathe and let air in and out. Hailey explores the architectural features of famous porches, like the one at the Resurrection Chapel by Sigurd Lewerentz and the approaches of several architects. Authors and artists seem to have a predilection for watching and working from porches, and Hailey describes the Florida porch of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, the porch-sitting of Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor and John Dewey, the porch-painting of Cézanne and the porch-photography of Paul Strand. Through all the examples, the book makes a strong case for the porch as an important locus where modern literature, art, and philosophy intersect the daily life of specific places.

Hailey invites us onto his porch in particular and, in so doing, invites us to consider the world from its tilt. What is it that Hailey wants us to weigh from the porch as we gaze up at its blue ceiling or out into the world through its screen? Many things. One of the chief considerations in the book is our relationship to nature. For while we spend most of our days inside, a porch is a liminal space, also partly outside: “A screened porch offers just enough closure for shelter but not too much definition for fresh air to lose its fidelity.” Here we “acclimate” and, in this process, can better consider climate, among other things. Describing his corner of Florida from his porch, Hailey can chart the hurricanes, the rising waters, and the shifting species of plants creeping north as waters warm. He writes that a “porch is that place where inside and outside mix, where architecture’s edges encounter climate,” which makes it ideal for observing.

When it comes to locations for considering ourselves in and not apart from nature, Florida may be especially good. Florida is probably one of the most air-conditioned and pesticided states, but it is not a place where you can fully escape nature. If you turn your back for a second, a lizard will sneak into your house. If you look the other way, an air plant will be growing on your fence. And if you’re not cautious, your books can rot (something which happened to Hailey in a previous Florida home). Florida is also a state stretching at the seams with population growth and development and the resulting problems of increased chemical runoff and habitat destruction. All the new neighborhoods and golf courses have created more toxic algae and threaten everything from seagrass to manatees.

Hailey emphasizes the porch as a frontier for viewing the world because it is experiential. The Florida setting is apt here, too, because there is something very “frontier” about Florida. In the book, Hailey points out that Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family were “climate pioneers” in the old Florida before air conditioning. In my part of Florida, some of the first white settlers are still referred to as “pioneers.” Florida is also a state which is and will be dramatically affected by climate change; it is a frontier for the future of coastal places. For Hailey, the best place to encounter and understand the changes to our climate (or perhaps anything) is the edge. No wonder Hailey makes references to Frederick Jackson Turner, and his frontier thesis, in this book. Hailey’s house is especially a frontier because it exists on the water; it is among the elements in a way that most houses are not.

Though climate change is one issue that concerns Hailey, The Porch does not present a straightforward environmental polemic as much as it offers an encouragement in ways of seeing. Ancient philosophers were often found on porches, and the Stoics even took their name from that. Through a porch’s unique elements, neither entirely indoors or outdoors, when screened and ceilinged with blue, “we have to practice seeing in, through, and around what we’re looking at.” There is a significant difference between staring at a computer screen and seeing the world through a porch screen. Hailey emphasizes the benefits of seeing from the “threshold between stability and precariousness,” which is nothing like viewing the world from the comfort of a couch in an air-conditioned room, even if the porch is also comfortable.

One of the reasons that make porches an excellent place to encounter the world is that they are a place where it is easy to welcome others. Porches are natural sites of hospitality. Hailey takes us back to the Greek tradition and its porches and practices of hospitality. But even today, porches are where it is easy to drop by and gather in a neighborhood, a place for unplanned visits. Some of my relatives who have lived in Indianapolis and Cleveland have benefited from neighborhood practices of “porch parties.” There is a Harrison Center in Indy devoted to them. A porch is personal and domestic but not private or requiring much for entry. As we encounter the world from a porch, we are able to do so alongside others, even if they are very different, without feeling that we are overexposed or overextended. There is something special about meeting other people in open air. In a recent column, Tish Harrison Warren noted that outdoor gatherings were something spurred on by COVID that her family has enjoyed and plans to keep. Porches are excellent places for meeting outdoors.

The emphasis on viewing the world from the porch also makes Hailey’s book what we might call “Wendell Berry adjacent.” All porches share certain elements, but each porch is particular—its own layers of paint, its own degree of tilt, its own rips in the screen. And Hailey encourages us not to view the world from all porches at once, but from one at a time. There is an emphasis on place and localism as grounding elements for understanding the world. We may seek to understand the wider world, but we do so by recognizing the plants and animals outside our own porch. For Hailey, learning to identify local birds is part of the process of understanding climate, recognizing local middens is part of learning history, and watching the storms is how we know when others might need assistance.

Many readers of Front Porch Republic will enjoy this book. It includes beautiful and detailed descriptions of nature seen from a screened porch and the thoughts about life that result. Like a river, the narrative path is not straight, but winding. At the end of the book, Hailey argues that “today porches may seem more like an amenity, but they are actually a new kind of necessity. Because porches reconnect to the wildness found not just in nature but in the newly wrought relations between humans and nature.” This is argument which will resonate with many FPR readers, who will likely find themselves longing for a waterfront porch and will also notice and appreciate his reference to “front porch” communities.