Lancaster, SC. “Why are you studying to become a lawyer when your brains are so obviously in your hands?” Such was the question that changed the trajectory of Doug Stowe’s life, and many others as a result of his lifework. I first came across Stowe in Fine Woodworking magazine years ago, where his unique box-making style and techniques were on display. Following the approach he so clearly laid out in the article, I tried my hand at making some. They were the best boxes I had ever made. In the furniture and woodworking world, Stowe has been a respected and prolific name for decades, frequently writing for a variety of notable woodworking magazines, publishing more than a dozen books, and teaching at the Eureka Springs School of the Arts that he helped found over twenty years ago.

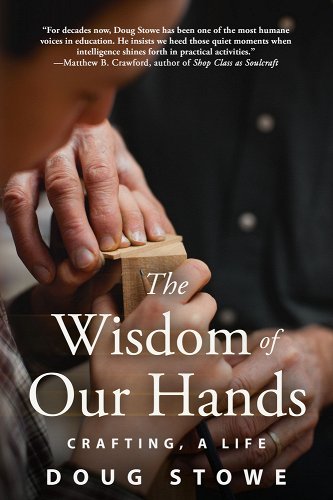

But all of this might never have happened if it weren’t for the blunt and honest question of Doug’s friend Jorgy who challenged the cultural norms about education and prestigious careers—and if it wasn’t for Doug’s willingness to take the risk. We need more Jorgys—and more Dougs. Doug Stowe’s new book The Wisdom of Our Hands: Crafting, A Life will help form both. The book aspires to two lofty goals, “to describe artisans’ personal growth as makers of beautiful and useful things” and to transform “human culture and economy by taking the hands into greater consideration” (xiii). From his unique perspective forged throughout a life that spans everything from 1970s activism to making wooden boxes that Bill Clinton presented as gifts of state, Stowe offers an intriguing vision of how craft and hands can form us as individuals, families, and communities.

Forming More Jorgys: Breaking Through Educational and Cultural Messages

In Stowe’s view, one of the contributing factors to a whole host of societal challenges today—whether it be the growing sense of meaninglessness and powerlessness or the mediocrity of American education—is the evisceration of the manual arts from our everyday lives and our educational experiences. The body, more specifically the hand, has a merely George Jetson, button-pushing role in modern education with its exaltation of math and science, going to college, and white-collar knowledge work, nor does it have a place in modern life with its penchant for internal identity, its airbrushed, hyper-glamorized human forms, and its digital technology. Stowe writes, “When you begin to understand the role of the hands in the creation of intelligence, you cannot help but notice the effects of current American education. To isolate the education of the mind from that of the hand and to separate those who have academic ambitions requiring college from those presumed ill-suited for academic pursuits and destined for the trades are costly decisions” (67). Stowe considers “the damage we are doing to ourselves and our kids by keeping them under housebound and school-bound sequestration from the natural world. We’ve become estranged, and we feel it. There are real physical and mental consequences from our detachment from the materiality of the world…. Engagement in this materiality offers rewards that our digital world does not” (20-21).

In contrast to this stark bifurcation of mind and body, Stowe offers a wholistic picture of how one learns by drawing on a range of academic disciplines and craft traditions: “the idea that human knowledge is brain based or language based does not provide an accurate view of who we are and how we learn. This is not to disparage the brain or language, but to point out the necessity of a whole body/mind approach to crafts and to life itself” (29). The manual arts are a perfect place for that balance of order and chaos to come together in a fruitful dynamic where intellectual, physical, and creative development can occur. This “possibility space” allows for the fostering of “islands of competence,” which build agency, confidence, and skills that transfer to other domains (73-74).

Stowe’s suggestions would require significant re-thinking and restructuring of school curriculum, something that Stowe has actual experience doing—he has taught woodworking to young and old alike for decades in a variety of settings and designed a K-12 school shop class curriculum entitled “Wisdom of the Hands” in Arkansas that is still in use today (121-122). Stowe has also played a key role in exposing Americans to Educational Sloyd, a Swedish program that over a century ago “was introduced into schools as a means of countering the most destructive modernizing forces in Swedish society” and is still “a compulsory part of Scandinavian education to this day” (86). Stowe explains that the Sloyd method “recognized the very close relationship between the use of the hands and the development of intelligence and character” and that “participation in crafts offered important values to students because it prepared them to thrive economically and socially in the industrialized world” (86).

Stowe reminds us that his friend Jorgy was right. Handwork is not mindless: “it offers reason for engagement and a foundation for excitement in learning that the basics of reading and math may not. It also develops the body, preparing it for efforts of mind in reading, science, and math” (92).

Forming More Dougs: From Handmade Goods to How Hands Make Us

If more Jorgys can poke holes in the educational and cultural narratives that are actually doing us such harm, we also need more Dougs who then take the risk and break free from them. This can start small, and Stowe offers much needed encouragement along the way: “while we’re waiting for the educational reform that experts acknowledge we need, one that engages the hands to their full potential, do not wait to give that opportunity to your own children and grandchildren. There are so many wonderful ways to engage them in learning about their world, hands-on. You, too, will find joy and inspiration in that” (94). Stories and anecdotes from Stowe and fellow craftspeople weave their way throughout the book and bring the ideas to life, as Stowe hopes the book is not “preaching to choir” but rather “choir practice, in the hopes that we all become better spokespeople for our hands” (xvi).

As the title implies, hands are central throughout the book, but in two senses. Perhaps the more obvious sense is how we use our hands to make things. But the other more subtle, yet perhaps more important sense, is how our hands make us. Hands play an integral role in our identity and in what it means to be embodied beings. “The hands have been the fundamental means through which the world has been shaped, measured, studied, and understood,” Stowe writes. “Hands are not only instruments of creativity; they are also sensing devices without which our understanding of our world would be incomplete” (24). The human body is meant for direct engagement with physical reality as human agency and freedom spring forth, making it even more lamentable that “people have been made less intelligent and have sacrificed mental health by refusing to recognize the integral relationship between our tools, our hands, and the creation of human intelligence” (65). Stowe reminds us that the work of our hands “is deeply real, not to be missed or mindlessly avoided” (88). For Stowe, it even becomes a sort of recognition or marker: “I’ve proudly worn the stamps of my woodworking as calloused hands, a trail of sawdust on my shirtsleeves and pant legs, and the blended aroma of wood dust and sweat” (2).

His juxtaposition of how hands interact with digital devices compared to traditional objects is also intriguing: “We cannot say as we watch a child’s fingers flashing around on their handheld digital device, that their fingers are not engaged. They can move those at a frenzied pace. But what about the full range of sensing and creative capacity that the hands offer? …Are there important things we learn about the world by being engaged hands-on, things we will not learn from our iPhones, our fingers sliding smoothly on glass?” (125). This connects nicely with philosopher Byung-Chul Han’s exploration of how “digital technology is making human hands waste away” as we deal less with “thingly things” and more with “unthingly information.” Han concludes that this “new man will finger instead of handling….digital man fingers the world” (32). Much like Han, Stowe concludes, “the hands are instruments through which our creative imaginations are brought to bear in transforming the material world. They are also sensing devices that confirm our reality and measure our sacred place within it” (129).

Using our hands forms us in more ways than we know: “Every act of making—whether in wood, metal, cloth, or clay—is a moral act, shaped by thought, belief, and desire. Craftspeople may not often think of such things, but as we go along crafting, making, selling, or giving our work, we perform moral acts with the power to transform not only our lives but the lives of those around us” (69). Thus, craft has both an interior and exterior orientation: “We are bodies with individual responsibilities, but by choosing to focus not on ourselves but beyond ourselves with a larger, wiser, wider view, we can discover greater meaning in life and greater connection with each other” (77). Stowe sees his work as connecting him to “a much larger world beyond my own hands and my financial situation” (78). All of this goes far beyond the individual towards the formation of family, community, and culture. Stowe puts before us a choice: “when it comes to the culture you inhabit and enjoy, you have the choice of whether you craft it for yourself, and thereby contribute something of yourself to the culture enjoyed by others, or you let it be delivered to you by parties unknown while failing to put forward your own creativity and originality” (124). Valuing hands, craft, and the people who make things breaks us free from the consumerist tendency to “acquire cheap stuff” that only perpetuates “a system in which useful things are expendable and quickly abandoned in our haste to acquire new, meaningless stuff” (152). Instead, “there is a profound shift when we change from consumers to makers” (155).

Handcraft also involves real risk. Stowe builds upon David Pye’s juxtaposition of a workmanship of certainty, where machines are set up “to reach high levels of accuracy and efficiency” and a workmanship of risk, where “the craftsperson’s complete and continuous attention is required, because if it wanders, the craftwork may fail” (45). Stowe argues that “the real value of the handcrafted is that when you embark on doing things you’ve never done, and you face risk of failure in doing so, you have an opportunity for personal growth” (145). The direct confrontation with reality that craftwork requires helps to keep us in our proper place—humble in knowing that we cannot construct our own reality in our own heads but must submit to the physical characteristics of the material being worked, yet confident in experiencing the growing sense of agency and competence that comes from increasing adeptness with our hands. Forming Dougs has ripple effects well beyond the individual.

Further Explorations and Connections

The framework I’ve used for this review, of forming more Jorgys and Dougs, is my spin on only a few strands in Stowe’s book. There are many others worth further reflection as well. I was impressed with the book’s clear and logical structure, which built a compelling argument: hands and handcrafts help form the self, which then radiates outward with significant benefits for the formation of family, community, and culture. Along the way, Stowe’s breadth of knowledge and research is evident, as he interacts with the usual suspects in this genre (Matthew Crawford, Michael Polanyi, David Pye, et al.) but also brings others into the conversation (I was glad to see Ivan Illich make some appearances). I’d also note that Stowe’s work here adds heft to the arguments of some of these more recognized names like Crawford. While Crawford’s best-seller Shopclass as Soulcraft is indeed a classic, is there at least some irony in the fact that he never attended nor taught a shop class? Stowe’s work in the realm of teaching shop and making furniture for nearly fifty years lends additional authenticity and credibility to the concepts they both have done so much to uphold and defend. Crawford writes a wonderful foreword to the book and notes how he quoted Stowe in both Shopclass as Soulcraft and The World Beyond Your Head, something I hadn’t noticed before.

Stowe’s reflections on forgiveness and craft I also found quite poignant. Forgiveness is an essential aspect of life in a broken world, and without it, humans have no real hope. When you make mistakes while crafting, you have to practice a sort of forgiveness and reconciliation in order to refashion the project towards its proper ends. The constant movement of wood and the inevitable mistakes that occur in each project make woodworking “an invitation to the simple matter of human forgiveness” (134). Just yesterday I found myself getting angry at a foolish mistake I made in the shop that will require additional work and ingenuity to remedy. What did my anger gain? Only setting a bad example for my kids, who overheard my outburst and wondered what went wrong. Christ have mercy. Thanks be for Divine forgiveness, which I may appreciate more deeply through the comparatively minor practice of forgiving myself for mistakes in the woodshop.

Stowe’s book is both timeless and timely. Our physical embodiment as human creatures is always essential, but it is especially so amid increasing digitality. The last two years of pandemic-related economic fluctuations and supply-chain instabilities have further driven home the importance of developing manual competence on a local and familial level, which adds to the book’s importance. The book also connects nicely to some other recent works. David Goodheart, in his book Hand, Head, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect, writes how during the past few years “many of us, perhaps especially the privileged and highly educated, have been forced to reconsider what we value most deeply and, having looked up from our busy, mobile, existences” were reminded “of the primary value of family and the hard work of nurture and education that takes place within its walls” (xi-xii). Similarly, Rory Groves makes a strong case for reconsidering the trades and productive home economies in Durable Trades: Family Centered Economies that Have Stood the Test of Time. So too, Chris Hall’s Common Arts Education: Renewing the Classical Tradition of Training the Hands, Head, and Heart has much to offer. Stowe has earned his place in a growing chorus of voices; to use his own analogy, that choir practice he’s been hosting must be working.

I haven’t read the book but this is a well-organized and deeply reflective review. I particularly liked the repeated emphasis on bodily experience.

Very good review of what appears to be a helpful book, even for someone like myself who is and always has been “all thumbs” when it comes to handiwork.

It’s funny, but when I was a kid I built models by the dozen and was pretty good at it. Somewhere along the way I lost the inclination for such things and with it went the skill, alas. Now I’m at the age where neither fingers nor eyes can always do what you want them to. Thankfully I’ve never been adverse to blunt work. I can rake leaves with the best of them, and furthermore have always enjoyed doing so.

Comments are closed.