Pittsburgh, PA. A recent conversation illuminated the rich yet fragile inheritance that multigenerational communities can be. Pam and I had a lot of time to pass in our long drive from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia. Diana, my girlfriend, recently moved across the state for a new job, leaving me and Pam, her best friend, in Pittsburgh. That weekend all of our schedules lined up for us to visit Diana in Philadelphia. On the car ride across I-76, Pam and I passed time by talking about our vastly different childhoods and how an underappreciated distinction separated our experiences.

Many of the variations are easily recognizable. Pam, and our shared favorite person Diana, are first generation, Asian-American, and female. Pam’s parents came from the Philippines while Diana’s fled after the collapse of South Vietnam. Pam is also from the sprawling metropolis of greater Los Angeles. Pam has only ever lived in cities and came to Pittsburgh for college.

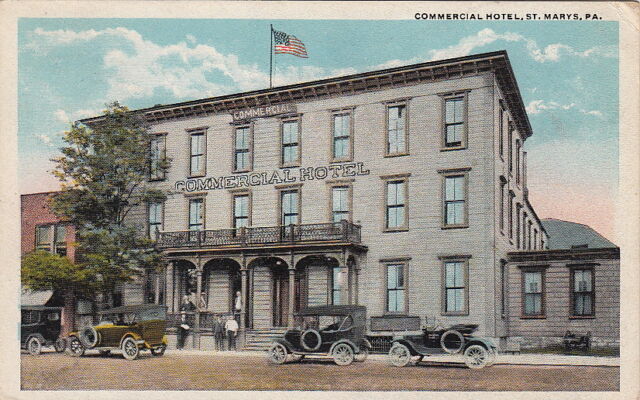

Meanwhile, I’m from the rural town of Saint Marys, Pennsylvania, male, and of mixed European heritage. But under those differences lies something which explains many of the divisions we witness in modern America. I am not only a multigenerational American—I trace some of my German lineage to at least the 1840s—but my family has only ever lived in my community, notwithstanding my recent move. My brothers have started families in our hometown.

Pam and Diana find this aspect of my upbringing odd but interesting. Many of my friends’ parents grew up with my parents. The grandfather of one of my best friends was drinking buddies with my grandfather, who was the town dentist. To this day, my last name Higgins is associated with the pipe smoking dentist and World War II veteran. My other grandfather is known across two and a half generations as the lovable high school guidance counselor. People are judged in my community by their last name. Familial associations are old and deep in a place like Saint Marys. The community’s population has perpetuated through self-sustainment, with immigration into the area ending in the 1920s with the Italians, to which I also share ancestry.

For Pam and Diana’s families, their success rises or falls with the success of America as a whole. Their family’s attachments don’t run deep in any one town or neighborhood, and many of their family members are highly mobile across the expanse of America. For my family, our lives has been tied to one rural community for over 150 years.

This dynamic is underappreciated in current discourse. Could some of our civic breakdown be explained by this phenomenon? I suspect so. For many Americans, especially those on the coasts, in cities, and with advanced educations, life has improved in recent decades. Meanwhile, in many rural and interior parts of the country, economic growth has stagnated or declined, along with the population. While America has improved for a certain type of American, many towns and places inhabited by multigenerational Americans, whose existence is linked to one community across centuries in some cases, have declined.

This is not an under-analyzed trend altogether, with much recent attention on the urban-rural and educational divides. However, the experiences of the multigenerational, communitarian American is under appreciated. Maybe this lens can gain traction as another tool for understanding our current political trends and cultural divides.

To begin, the institutions that sustain a multigenerational community are much different from ones that support places like my adopted home of Pittsburgh, which feature far more mobile and cosmopolitan Americans. The economies of places with high concentrations of multigenerational Americans often depend on one key business or industry, such as archetypical factory towns of Ohio, the agricultural communities in Nebraska, or resource reliant oil towns throughout west Texas. For these communities, generations are sustained by one fixed, economic institution that experiences low turnover. This low turnover is a feature, not a bug, because the knowledge to sustain these industries is passed down informally through generations rather than through formal institutions, such as a university.

Meanwhile, areas increasingly devoid of high concentrations of multigenerational Americans feature high turnover, like Pittsburgh’s economy that is centered on healthcare and higher education with a budding technology sector. For these communities, many individuals pass through them by design, such as students and professors, nurses, doctors, and patients, and highly educated young professionals. These institutions and corresponding economies transmit knowledge on how to run them through formal, professional institutions rather than the vernacular institutions of family and community.

Because of this, life in a multigenerational community can be incredibly rich in ways that are hard to account for. Family bonds can extend throughout an entire town and across many generations, homes and pieces of land can be passed down generation to generation, multiple generations are sustained by the same vocation, and local traditions grow from such closeness.

My own decisions have been influenced by these forces. For instance, when I had a will made during my time in the Air Force, I made one specific request: I was to be buried in Saint Marys. Before joining the military, I tended to the graves of past generations when I worked as a weed wacker at a cemetery. Being buried anywhere other than Saint Marys was utterly foreign – though subconsciously at the time. I had to be buried near relatives.

But social breakdown in a multigenerational community can be particularly devastating, as we’ve witnessed the past couple decades. The economies of these places are interwoven across generations and civic institutions. If an economy of a multigenerational community is destroyed, other institutions crumble with it. Families, churches, and local schools buckle when social decline follows the wake of economic dislocation.

What is a multigenerational community to do when such a process is underway? There are no easy answers, and decades of technocratic fixes in state capitals and Washington D.C. have produced poor results. My belief is that many of the communities that have turned to populist leaders in recent years are multigenerational ones. When forces of social, economic, and demographic change happen quickly, multigenerational communities often don’t have the tools to adapt, because the whole community was sustained by the same set of now depleted institutions.

Solutions to address the decline experienced by some multigenerational communities won’t come easy. Leaders, populist and technocratic alike, have so far failed. But perhaps we need to broaden our lens when analyzing American life and understanding its various communities. Recognizing that many Americans have multigenerational attachments to one specific place in our vast country is a start.

Thanks for sharing a deep personal insight. Perhaps it’s useful to temper the dichotomy by recognizing each new generation of family doctor in your hometown probably did train in an urban center, possibly out of state.

I don’t understand this sentence:

“My belief is that many of the communities that have turned to populist leaders in recent years are multigenerational ones.”

Is populist a bad thing? I thought media praised Obama for being one in 2008?

Seth,

Thank you for this insightful article. Have you read Jewett’s “Country of the Pointed Firs”? I think there is a “telling” there about the generations all the way back to the medieval courts and further to the ancient gods…you have to dive into Jewett’s layers to find it – but it is worth the plunge.

Comments are closed.