Grove City, PA. With characteristic understatement, Matthew Continetti begins his history of the modern conservative movement in America, The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism, by conceding that he is “not an entirely disinterested observer.” Indeed, as a free-thinking undergraduate at Columbia University, Continetti devoured the works of conservative thinkers and journalists of the 1950s and 1960s. Then, at the venerable age of twenty-two, he joined the staff of the neoconservative Weekly Standard near the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003. In The Right, Continetti seeks to “tell the story of the American conservative movement through the experience of its participants.” Neither an intellectual history nor a “political sociology,” the book is a detailed account of the main political actors and journalists who have led the diverse movement (5). For Continetti, the principal engine driving this history has been the battle between extremism – politically destabilizing populists – and authentic conservatism – small government constitutionalists. This latter group, drawn primarily from more elite circles, has better appreciated that electoral success comes when conservative ideas appeal to the larger American mainstream, rather than simply to the hard Right.

The author wisely begins his story not in the 1950s but during the 1920s. Under presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, conservatives repudiated the government activism of Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and their Progressive supporters while venerating constitutional strictures. Two important developments derailed this conservative reaction. First, the Great Depression ended the prosperous Twenties, and, second, FDR’s New Deal brought significant structural changes to both the economic and political orders. Much of the postwar conservative movement had its early roots in organized opposition to the New Deal and to Roosevelt’s pragmatic policies that some critics deplored as fundamentally un-American. But, as Continetti notes perceptively, conservative groups like the Liberty League “had no power base other than pockets of industry and parts of the enfeebled GOP.” As a result, the emerging movement “tended to adopt an adversarial and catastrophizing attitude toward government that it never quite shook off” (39).

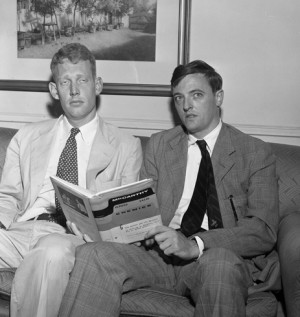

World War II discredited the isolationism of the Old Right and set the stage for the emergence of the Cold War. As bipartisan concern over the Soviet threat grew, anticommunism became the hallmark for a new Right, which was an alliance of discordant elements. Soon, socially conservative traditionalists, economic libertarians, religious conservatives, and other strands rallied around the anticommunist banner. The movement that took shape during the early fifties mostly supported the demagogic anticommunist crusade of Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy, despite the reservations of some regarding McCarthy’s unscrupulous tactics. Meanwhile, William F. Buckley’s polemic God and Man at Yale (1951) helped define the movement’s principal target–secular liberals who allegedly sought to appease the Left. Buckley’s subsequent founding of the National Review (NR) provided the new movement with an essential public forum to articulate its ideas.

While NR appealed mostly to conservative elites, both Buckley’s circle and more populist elements came to support Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater in the early 1960s. In retrospect, Goldwater’s drubbing by Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential contest marked not the end of the movement but the beginning of its ascendancy within the Republican party. Ronald Reagan’s famous televised speech (“A Time for Choosing”) in support of Goldwater during the 1964 campaign indicated that the former actor would be a far more attractive and winsome movement figurehead. Reagan, who was elected governor of Californian in 1966, deferred to Richard Nixon in 1968 and therefore had to wait until 1976 to launch an effort for the Republican nomination. Though he failed then to unseat incumbent Gerald Ford, his attempt set the stage for Reagan to win the Republican nomination and crush Democratic President Jimmy Carter four years later. The Reagan administration drew ideas from neoconservative public intellectuals like Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol, both former Leftists who by that time deftly appealed to rising populist prejudices against liberal elites. Another key element in the conservative alliance were white evangelical Protestants whose increasing political engagement had been noted by many commentators by the mid-1970s.[1]

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought profound changes to the conservative movement. Continetti observes that “lacking an external threat of Soviet communism’s magnitude, conservatives [gradually] turned inward… [and] became more southern, more religious, and more nationalistic” (297). The revised “compassionate conservatism” of George W. Bush proved to have limited popular appeal, especially when the invasion of Iraq failed spectacularly and the war in Afghanistan dragged on. An increasingly radicalized Republican base rebelled in the wake of the nomination of establishment favorite Mitt Romney in 2012. The emergence of the rebel Tea Party movement highlighted that populists were following more closely the agenda of talk radio hosts such as Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck rather than that of party elites.

When Trump attracted substantial support from Republican voters during the 2016 party primaries, some of the old guard conservatives were caught flat-footed. It scarcely mattered when the editors of NR produced an “Against Trump” issue prior to the Iowa caucuses. As Continetti explains: “Donald Trump did not need National Review. He had Twitter. And talk radio. And, increasingly, the Fox News Channel itself” (370). After summarizing Trump’s single term in office, the author concludes soberly:

What began in the twentieth century as an elite-driven defense of… classical liberal principles… ended up… as a furious reaction against elites of all stripes. Many on the right embraced a cult of personality and illiberal tropes…. But a conservatism anchored to Trump the man will face insurmountable obstacles to attaining policy coherence, government competence, and intellectual credibility (411, 413).

The foregoing condensed synopsis doesn’t do justice to Continetti’s detailed treatment, but much of this movement history is probably familiar to FPR readers. Continetti’s rendition is distinctive in its focus on the tension and recurrent clashes between an increasingly radicalized populist grass roots and movement elites committed to a principled small government constitutionalism. Academic historians of the movement will be skeptical about the tidy simplicity of that portrait. They correctly see the division less as a battle between two distinct groups and more as a complex marriage of convenience, a relationship that entailed much more than what Continetti terms “occasional cooperation” (5). To cite only one minor example, former Republican Congressman and committed fiscal hawk Mike Mulvaney readily jumped on the Trump train as Budget Director and then openly mocked traditional concerns about growing deficits.

Further, this story of authentic conservative elites battling populist extremists underplays the hypocrisy and failures of elites dating back decades, long before Trump. As Continetti’s own account concedes (though fails to pursue), leaders like Buckley defended McCarthyism and were careful not to alienate the John Birch Society’s rank-and-file. Continetti himself defended the patently incompetent Sarah Palin in The Persecution of Sarah Palin: How the Elite Media Tried to Bring Down a Rising Star (2009).

The lack of a deeper critique may stem partly from the author’s failure to interact with the rich scholarly literature that has appeared since Alan Brinkley’s seminal 1994 article “The Problem of American Conservatism.” While the book’s endnotes indicate that Continetti sampled some secondary sources (such as Alan Lichtman’s White Protestant Nation: The Rise of the American Conservative Movement), he did not engage the rich historiography about conservatism, apart from noting that the Left and Right approach the subject differently. These more academic treatments of the subject shouldn’t be dismissed as a simple “pathologizing [of] conservatism” (7).

Continetti correctly argues that the movement didn’t simply pop up suddenly after WWII. Unfortunately, his ambitious decision to start with the 1920s and his thorough chronological approach leads his interpretation and analysis to often be sidelined by his effort to provide an exhaustively detailed history. Given his focus on the elite/populist struggle, it is also odd that the book doesn’t investigate more fully how talk radio and the internet essentially removed the movement’s traditional gatekeepers such as Buckley, or later, editorialists like George F. Will. His simple observation that “wild accusations zipped across the Internet at light speed” is plainly inadequate (359).

Continetti candidly notes that “substantial elements of the American Right, including many GOP officials, accommodated Trump” in encouraging the violent attack on the Capitol on January 6, 2021 and continuing to lie about the 2020 election (401). Yet he fails to explore what that says about the “conservatism” of today’s American Right in general. If, as Continetti declares in his last sentence, “the job of a conservative is to remember,” then how can a grifting real estate mogul with no appreciation for any tradition, let alone historic constitutional norms, now stand as the figurehead for the movement? (415).

Despite these problems, The Right is more honest and self-critical than other insider accounts. Continetti writes clearly, and the story, if oversimplified and occasionally self-serving, is an illuminating, engaging, and enjoyable introduction for those who want a popular – but not a populist – chronicle.

—

Continetti curiously asserts that Reagan “restored the ethos of ‘Calvinism’ to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.” Only a few sentences later, he correctly observes that Reagan “believed in the innate goodness of people.” Whatever is meant here by Calvinism must be something different from the teaching of John Calvin.↑