Arlington, TX. I’m beginning to suspect Apple is making telescopes for NASA.

Dr. Jane Rigby, an astrophysicist and operations director for the new James Webb Space Telescope recently shared during NASA’s live press conference that she had an “ugly cry” when she saw the first images taken by the Webb:

“Earlier than this, the first focused images that we took where they were razor-sharp…that for me had the very emotional reaction like oh my goodness, it works. And it works better than we thought…personally, I went and had an ugly cry. What the engineers have done to build this thing is amazing.”

Note her ugly cry was about the telescope, not the heavens themselves. As the late social critic Neil Postman put it: “To a man with a camera, everything looks like an image.”

Never mind the stars, weep because the telescope works. NASA’s official Twitter account endorsed Dr. Rigby’s sentimental outpouring by quoting her: “Personally, I went and had an ugly cry. Because it works.”

This weeping over a piece of technology is just the sort of enthusiasm Tim Cook and company are known for generating about their products. I surmise that if I live long enough, Apple will either admit they built the Webb, or they will eventually create a phone that could do pretty much anything the Webb does. The Webb, then, it is merely the latest exhibit in the narrative David Nye lays out under the heading of the “American technological sublime”: we are no longer awed by natural grandeur but by the grandeur of our own technological accomplishments.

And what exactly is the average person in the street supposed to do when corporate astrophysicists tell us that the most distant galaxy in the universe has signatures of oxygen and hydrogen in it? Cry?

In addition to a beautifully variegated array of galaxies and nebulae, Webb also discovered water vapor in an exoplanet. Immediately, talk of “earth-like habitable planets” began. Yes, but let us remember one can also detect water vapor in abundance in the Dead Sea, where nothing lives. For my two cents, astrophysicists should be prohibited from using the term “earth-like” until one of their telescopes can actually see something like elephants and giraffes and sea lions milling about on the surface of a distant world.

“Consider what goes on when you lay the table for guests,” philosopher Sir Roger Scruton says in his short essay on beauty, “you will not simply dump down the plates and cutlery anyhow. You will be motivated by a desire for things to look right – not just to yourself but to your guests. Likewise when you dress for a party or dance, even when you arrange the objects on your desk or tidy your bedroom in the morning: in all these cases you are striving for the right or appropriate arrangement, and this arrangement has to do with the way things look.” This is what the Greek word kosmos means. It is first and foremost an arrangement. It is from this word we get the word cosmetics.

The cosmos is the ultimate arrangement and we are the guests. As the late physicist Freeman Dyson quipped, “the more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense must have known we were coming.”

I don’t claim to know what exactly goes into an ugly cry, but I’ve seen a few instances where, in the presence of ocularly-induced water, mascara runs down the cheek like mud ejected from the Mississippi at flood stage. It’s not pretty. Especially at a dinner party.

But the universe is beautiful and NASA doesn’t know why. That ought to be reason enough for weeping.

In order for us to even have parties, mascara, tears, and telescopes in the first place requires an enormous amount of prearranging. No one is putting on mascara or hosting a gala if the gravitational constant of the universe was altered ever so slightly. No stars or make-up application if the weights of the electron, proton, and neutron were altered to any slight degree. And we are additionally fortunate that the atmosphere of Earth is not only just the right combination of gasses conducive to our sighing and breathing and crying but also doesn’t crush us, as the atmospheres of Venus or Jupiter certainly would.

So who did all this arranging? The Webb won’t tell us and neither will NASA. “Who?” the good scientist tells us, is the wrong question. The preeminent cosmologist Sean Carroll even goes so far as to claim that asking why the universe exists is something like a fallacy of quantum proportions: “The demand for something more – a reason why the universe exists at all – is a relic piece of metaphysical baggage we would be better off to discard.” But how does Dr. Carroll know what kinds of metaphysics empty space prefers?

In our sophisticated era of device worship, we are assured that big science has moved on from superstitious tales about the gods, having exchanged their birthright for a pottage of computational silicon and costly altars of fire from which are sent votive offerings to the impersonal forces of empty space which gave us life. But the sand in NASA’s computers and cameras and the strange conflagrations on their altars will remain silent, though the scientists seek answers with tears.

And for all the enhanced resolution of our universe Webb brings, for all the material analysis this new device supplies to scientists’ burgeoning cosmic databases, informing the denizens of Earth just what the universe is made of, NASA is not one whit closer to explaining what the universe actually is.

It brings to mind a scene from C.S. Lewis’s Voyage of the Dawn Treader. In the story, the crew of the sailing ship, the Dawn Treader, comes upon a mysterious island on which they encounter a “retired star.” The character Eustace Scrubb – a rather petulant lad who, arguably, models the modern world’s obeisance to science and who loves “books of information” – tells the aged star Ramandu that in his world a star is just a “huge ball of flaming gas.” But Ramandu gently reminds him, “Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is but only what it is made of.”[7]

Through Ramandu, Lewis gives readers a tacit allusion to the 19th Psalm, where we read, “The heavens are telling of the glory of God and the expanse declares the works of His hands.” But the only handiwork taking center stage at NASA is the telescope.

Webb’s new pictures are of deep-sky objects that the 32-year-old Hubble Space Telescope has already shown us. But it was not these objects that reflect the glory of God which brought Dr. Rigby to tears; rather, the image sharpness, contrast, and colors between the Hubble and Webb images are what seemed to have elicited Rigby’s ugly crying.

And an ugly cry it is.

In the Bible, when people weep and cry over inanimate objects, God calls it idolatry: “Their idols are silver and gold, the work of man’s hands…They have eyes but they cannot see…Those who make them will become like them” (Psalm 115, NASB).

I don’t mean to demean the work Dr. Rigby and her team have accomplished. It truly is exciting and satisfying to do a job well. But when you encounter all the luminous wonder of the cosmos in stunningly vivid detail to the extent Webb has revealed and your initial reaction is awe and wonder, not about the heavens, but about the device your hands have made – well, that about sums up where we are as a culture.

The more disconnected from our Creator we become, the more we will become like those impersonal and lifeless things which disconnect us from our Creator.

And despite the fact that our tax dollars went to pay for the Webb, none of us are going to get any access to it. In addition very few of us actually will ever be able to fully understand how the telescope works or have even the remotest chance in having a voice about what it all means (unless you can do physics).

This means that there are only an elite few scientists and engineers who are governing the telescope’s use and interpreting the data it yields. Postman put the problem this way: “those who cultivate competence in the use of a new technology become an elite group that are granted undeserved authority and prestige by those who have no such competence.” Postman goes on to note that “technologies create the ways in which people perceive reality, and that such ways are the key to understanding diverse forms of social and mental life.”

And just what have the science popularizers been telling us for decades now about our place in the cosmos?

The late planetary astronomer from Cornell, Dr. Carl Sagan, sums it up this way: “On the scale of worlds – to say nothing of stars or galaxies, humans are inconsequential, a thin film of life on an obscure and solitary lump of rock and metal.”

Our star is ordinary. Earth is nothing special. Neither are we. The universe wants to kill us.

After reading just twelve pages in one chapter of science popularizer and astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s book Astrophysics for People in a Hurry, I wondered why I was feeling a tad uneasy. I went back and found these words: “collide,” “mess,” “warped,” “bursts,” “spawned,” “violent,” “collision,” “strewn hither and yon,” “escaped,” “blobs,” “adrift,” “mayhem,” “flotsam,” “ammo,” “exploded,” “smithereens,” “homeless,” “cannibalism,” “ripped apart,” “consumed,” “corpses,” “eaten,” “junk,” “monstrous,” “hazardous,” “death,” “suffocated,” “dangers,” and “seething.”

For most of our human history, however, the heavens were not perceived as a terrifying demonic character in a Stephen King novel, but rather a helpful and beauteous creation of the gods – or God Himself. The stars provided a divinely arranged calendar which kindly condescended to our terrestrial creatureliness. Our views of the heavens were unobstructed by esoteric devices and light pollution. We encountered their luminous richness in person, like being wrapped in a mother’s handmade quilt.

The layperson also had a very broad and practical knowledge of how the heavens go. Yet could any of us today figure out when to plant potatoes based on naked-eye observations of the Pleiades? Would any of us know how to sail the open waters of the Pacific in a canoe using nothing but the stars as a guide?

But now that most of us can barely see a star in the sky because of the ever-widening gyre of the ugly grey-green metropolitan light pollution, the heavens have little place in our everyday lives. Even if you did decide to dive into the wonders of the cosmos online or at your local bookstore, you are likely going to find variations on the themes of Tyson’s death-monster universe or Rigby’s ugly crying over her new camera.

What is to be done? Dante knew the truth: it is love that moves the sun and other stars. Turn off your devices, go find some dark skies and be silent for a while.

On the literary side of things, if you’re looking to rekindle your wonder and awe of the heavens, Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia is a good place to begin. Ward’s insightful look into the cosmic imagination of C.S. Lewis in part inspired our book The Story of the Cosmos – How the Heavens Declare the Glory of God, which I also unashamedly recommend. Another antidote to Tyson’s monster-universe horrors is The Friendly Stars, by Martha Evans Martin and Donald Howard Menzel.

May the Lord and Maker of the heavens and earth be gracious to us and wipe away all our tears.

Soli Deo Gloria.

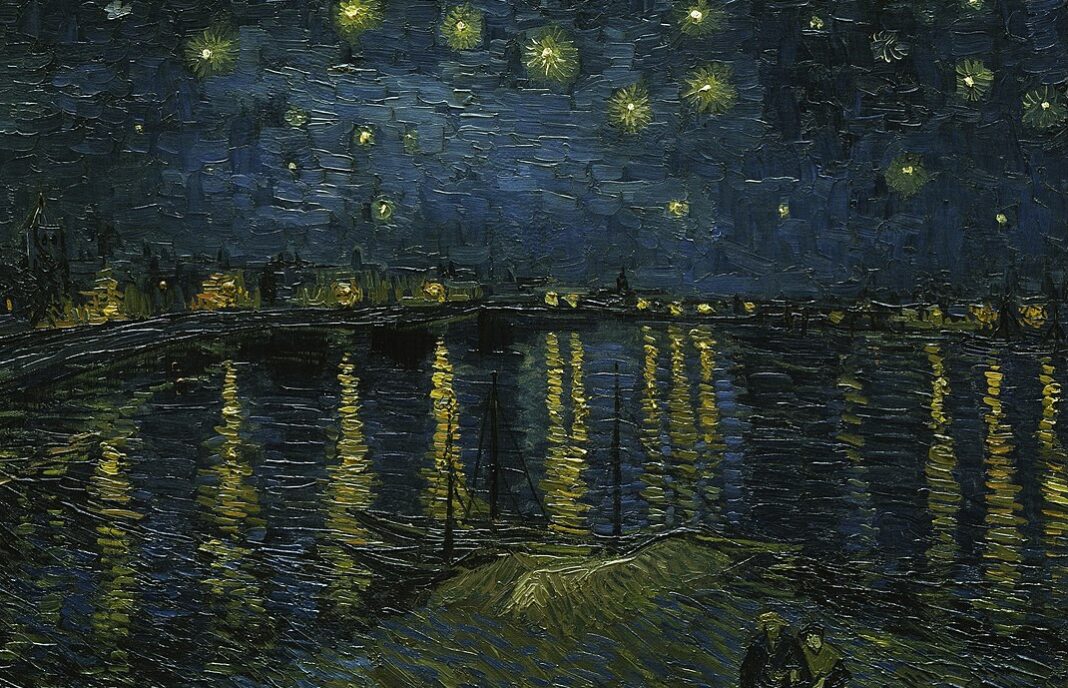

Image Credit: Vincent Van Gogh, “Starry Night over the Rhone,” 1888

Most Americans can’t even see the stars, just a few points of light in the night sky, dim above the cityglow. I am blessed to live in a part of the country where we have the least light pollution in the US, and can see the Milky Way in all it’s grandeur. If a person wants to be humbled and exalted at the same time, that is a good way to go.

Don’t blame the poor souls who can only see through a technical lens, they know no better. Some one or two may figure it out, eventually: STEM to do the job, Humanities to know which job to do, Faith to know whether it was a good thing to do that job anyway. (But let us not wax Aristotelian.)

Who exactly is to blame for light pollution? Neighborhood residents increasingly nervous about security who “solve” the problem with brighter street lights? Vehicle manufacturers who offer LED headlights that blind approaching drivers?

A recent FPR article on this topic quoted Nat Geo, which parroted warnings about “blue light” that we see heeded by dentists when they use blue light to “cure” filling material. I wonder if those warnings are rooted in studies of fluorescent bulbs, which contrast with yellowish incandescent light bulbs, that in turn have been replaced by long-life bulbs which *mimic the spectrum of sunlight* (so how exactly are they deleterious to human health?).

I’m very thankful that the JWST is working – especially given all the plausible failure modes that could have rendered it a $10 billion paperweight floating in space before its mission even started. I can hardly imagine the joy that must be felt in its initial success by the myriad of people who have invested the past 2+ decades in its design and construction.

I’m excited for what it will reveal about God’s creation as it undertakes its mission, and I’m praying that the beauty it reveals, the discoveries it leads to, and the further questions that those discoveries will inevitably raise will lead some people to ask the deeper question of “why” and seek God who reveals His divine nature through what He has made.

As an aside, Destin Sandlin who hosts the Youtube channel “Smarter Every Day” (and is also a Christian) has a few informative videos about the JWST.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4P8fKd0IVOs

It’s an incredible feat of engineering and a generational leap – far more than just “next year’s model of space telescope.”

https://www.inverse.com/science/what-comes-after-jwst

This is a good outline of the basic technical differences between future proposals and what the goals are. Sure it’s a lot of money. Not as much as has been thrown recently at vaccines and wars though.

I’m sure the countless engineers who worked to put the first known human on the moon were emotional about the success of their work before calmly contemplating its significance in human history (which media had already covered before the landing).

Daniel, this article started very strong and I found myself nodding agreement enthusiastically until I hit the bogus quote from Psalm 115, which doesn’t mention “weep” or “cry” at all. Or perhaps that was just a rough transitional paragraph?

I also don’t see the point of quoting isolated words from Dr. Tyson, who has fallen into the typical “public intellectual” trap of responding to requests to pontificate about topics outside his original expertise. Years ago that was called a “know-it-all” rather than an esteemed expert. You made most of your other points clearly by quoting full sentences, which show at least some regard for context.

Hi Martin –

Thank you for taking the time to reply and offer your thoughts. I appreciate your insights.

Briefly, the article was not an attempt to disparage human technological achievements per se, rather it was a rhetorical check on our sinful propensity toward idolatry. Perhaps I failed in that regard.

As for Psalm 115, you are correct that it doesn’t mention weeping or crying. Herein I attempted to make a subtle point. Idolatry makes us mute, it silences us, ruins the “mannishness of man” as Schaefer called it. We trade our Imagio Dei for sand. Though we have eyes, we cannot see. Though we have mouths, we cannot speak. Our weeping and crying is in vain. So yes, there indeed is no crying or weeping in Psalm 115 because idols cannot weep or cry. “Those who make [the idols] will become like them.”

I set this idea up when I said “But the sand in NASA’s computers and cameras and the strange conflagrations on their altars will remain silent, though the scientists seek answers with tears.”

Our idols cannot answer our most important questions, in other words. Our “cries” are non-existent and go unanswered. We know quite a bit about what we’re made of, what the universe is made of, but none of our most sophisticated devices can actually tell what the universe is or who we are.

The reason Carroll wants to discard the metaphysical questions (as did Hawking) is because they well understand their best technology is incapable of answering them. It is a concession to idolatry and precisely what Psalm 115 (and Romans 1) are saying. But in jettisoning the metaphysics we are paving the way to deposing our very humanity. Nature becomes the tyrant.

As for Tyson, his chapter is cited for context if anyone desired to pursue it. Tyson, however, is not alone in the idea of a violent and brutal Steven-King-like cosmos that wants to eat us for lunch. Sagan postulated it in a very similar style and I have several other examples of this same sort of “monstrous prose” in popular astronomical literature (nature red in tooth and claw).

But as in any attempt to express one’s self in prose there will always be a host of problems from what is left unsaid. And because I am a fallen and sinful human being, the best I can do is reflect upon and describe as best I can what I see dimly in the mirror (1 Cor. 13).

Thanks Martin.👋🙂

And a post-script, I also recently interviewed Apollo astronaut Charlie Duke. This is part one of five segments: https://youtu.be/WmGsoZklgcs

Thanks for a humble and informative reply, Daniel. Here’s a short video by astronaut Chris Hadfield about various myths (some true!) regarding space flight:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t6rHHnABoT8

He’s an entertaining speaker and has a longer clip about fictional space movies:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RkhZgRNC1k

nice

Comments are closed.