Grove City, PA. While away from the Internet last month, I had the opportunity to travel to Wales for a fantastic conference at Brecon Cathedral organized by Mark Clavier. The conference’s theme, “Inhabiting Memories & Landscapes: A Cross-Disciplinary Engagement with Wendell Berry,” drew a mix of attendees, from North American academics interested in the writings of Berry to Welsh locals and scholars from across the UK working on history, accounting, art, and more. The conversations that resulted were rich, and my reflections here merely pick up on a few of these threads.

The conference was first scheduled for 2020, and in preparation for a trip to Wales, I re-read all of R.S. Thomas’s poetry and much of his non-fiction. (I reflected at length on Thomas in this essay, which I wrote at that time.) During the conference, one of Thomas’s poems in particular kept coming to mind. Addressing the Welsh peasant figure Prytherch, Thomas concludes,

You were on the old side of life,

Helping it in through the dark door

Of earth and beast, quietly repairing

The rents of history with your hands. (Collected Poems 164)

This image of repairing the rents of history has at least two senses: on the one hand, these rents refer to the gaps, to the losses, to that which has been forgotten. In a more specific sense, though, these rents also refer to the wrongs and sins of the past that demand restitution and repair in the present. So often—as many of the conference presentations brought home—the latter rents cause the former: when people are forced off the land, traditions of caretaking and habitation vanish. Inhabiting our places well in the wake of such losses requires us to, like Prytherch, stand on the side of life and set about the slow, careful work of repairing history’s rents.

Near the end of the conference Mark mentioned that perhaps a definitive feature of our current age, one often dubbed the Anthropocene, is a lack of memory. To adapt the Latin word for forgetting, he suggested that we may be living in the Obliviocene. The mass uprooting of individuals and communities—whether pushed from their land by war or climate disruptions or political acts or pulled away by economic opportunities—results in the loss of memories that can only survive when intact communities remain in a place for generations. The ways in which our digital media ecosystem focuses attention on a narrow slice of presentist, superficial issues exacerbates these losses.

As Paul Kingsnorth’s novel Wake reminds us, time and again the people dwelling on the land have been driven off of it. When Buccmaster declares, in the aftermath of the 11th century Norman invasion, that “all is broc,” he gives voice to a perennial tragedy, one experienced by those who suffered the European colonization of the Americas, the Highland clearances in Scotland, the agricultural policies and potato famines in Ireland, or even less violent measures like the English Inclosure acts and the twentieth-century policies in America that took as many as twenty-five million people off farms in the twenty years following World War II (for more on this last one see, of course, Berry’s Unsettling of America). Many of those pushed or pulled off the land make new homes elsewhere, but the costs of this uprooting are still borne. And as Joshua Kraut observed in reflecting on the connections between Wendell Berry and the French philosopher Fabrice Hadjadj, uprooted, lonely souls are prone to violence. People who have been isolated and dis-membered will be more likely to lash out in anger and violence.

Several of the talks looked at particular instances of land loss and the longterm consequences of such uprooting. David O’Hara reflected on his experiences learning from a dwindling indigenous group in Guatemala. In a similar vein, Ryan Turnbull spoke movingly of his efforts to remember the indigenous people who once lived where his ancestors settled in Canada. This is not an easy task; so much energy was invested in forgetting these people that this work of recovery is difficult.

Even when there is no clear blame to assign for such oblivion, the consequences linger. The first evening of the conference, John Gibbs took many of us on a walk along the canal, built in the late 18th century. We turned down a lane where he then stopped at each house and gave a brief history of the building and its various owners and inhabitants. The next morning at the conference, John reflected further on the challenges of passing on these memories to the next generation. This becomes particularly difficult when, as Jonathan Williams described, many of the residents have left and many of the stone homes or cottages have vanished. It was only as economic forces were pulling people off the land that the Brecon Beacons National Park was established in the mid twentieth century. The preservation policies in the UK—as in America—remain oriented to the desires of holiday visitors rather than rural inhabitants.

Later on our travels, we visited an ancient stone circle in Castlerigg. Watching my daughter clamber up each standing stone drove home for me this sense of history’s rents and gaps. Based on what I could tell from the signboards there and some Internet reading later, we have almost no clue who hauled and erected these stones or what purpose motivated them. Like the Iron Age hillfort we hiked to that overlooks Brecon, this monument testifies to an ancient habitation here about which we remember almost nothing.

Yet even from our ignorance and forgetfulness, necessary questions emerge, and one of the great gifts of this gathering was in the way it focused our attention on intractable questions that require us to live out their answers, a little at a time: How ought we to remember what and who has been lost? From David O’Hara: “What kind of economy would cherish trees?” From John Gibbs: “How do we pass on the memories we have managed to gather?” From Norman Wirzba: “What must we learn to nurture the place on which we depend?” From Louise Franklin: “How do you encourage students to see slowly and generously?”

A first step toward answering such questions may be simply looking around us and attending to the histories of the places in which we find ourselves. Norman Wirzba quoted John Ruskin to the effect that to see properly you have to know the biography of what you’re looking at. Present understanding is the fruit of learning a personal history.

In this vein, one of the perhaps paradoxical lessons on offer at the conference was that newcomers and incomers can sometimes bring keen insight into a place and its history. Oliver Fairclough described how some of the people who moved into rural Wales to retire or get away from urban centers work diligently to learn the history of their new home and share it with others. Newcomers—whether those who move to a gentrifying urban neighborhood or those who want affordable property and a rural lifestyle—can be respectful and humble additions to a community and can often bring new perspectives and appreciation for a place. Other speakers, notably William Gibbs, pointed to the legacy of artists such as Eric Gill, David Jones, and others who came to this part of Wales and sought to recognize and render its beauty.

The imaginations of such newcomers, however, need to be disciplined by the particular realities and needs of a place. Several papers returned to this work of correction, but Christina Lambert’s reflections on Jayber Crow were particularly insightful. She traced the way in which Jayber’s naive, romantic, selfish love for Mattie Chatham is corrected and redirected over the course of his life. Our initial affections for a place or a person are often self-centered, and they need to be judged and redeemed in order to result in genuine, redemptive love. As Jayber Crow models in his narration of his life story, the work of memory entails precisely this work of judgment, correction, and refinement with the goal that we might participate in divine love.

Such genuine love was perceptible in the remarkable setting and context of our gathering. We were surrounded by the cathedral’s gothic architecture and its many beautiful memorials to those buried here. Mark and Sarah Clavier were generous hosts and guides. Our lunches, tea and biscuits, and conference dinner were all locally made and delicious. Even while we ate sitting beside the stone on which, apparently, archers from this region sharpened their arrows before heading to the Battle of Agincourt, we experienced the conviviality that can emerge from loving care.

Such care may only be possible if we first take up the work of memory. In his new book, The Need to be Whole, Berry sums up his understanding of our predicament: “both the land and the people are unhealthy.” And he suggests that “to deal with so great a problem, the best idea may not be to go ahead in our present state of unhealth to more disease and more product development. It may be that our proper first resort should be to history: to see if the truth we need to pursue might be behind us where we have ceased to look.”

In a rootless age there is a new hunger for the past, but much of this appetite seems misdirected. Treasure hunters roam Britain armed with metal detectors. Immigrants send in DNA samples to try to trace their genealogical origins. Endangered cultures sell commodified bits of their heritage to tourists. None of these are bad in and of themselves, but they merely preserve broken fragments of the past as often as they lead to actual healing. The real challenge is to make the wisdom of the past live in the present. Such work is analogous to sprouting a seed, playing a song, cooking and enjoying a family recipe, reciting the Lord’s Prayer with heartfelt fervor. And for this work to be sustained, we will need rooted communities that can hand such memories of care from generation to generation. When memories are abstracted from their origins, they often become brittle shards, easily wielded by demagogues or marketers. Or course rooted memories can be unhealthy in their own ways: they can molder and foster resentments and prejudices. Nevertheless, the best alternative to these toxic forms of memory is not a cosmopolitan cabinet of curiosities, but a redemptive and forgiving and sustaining community of memory.

Such communities have always been endangered, and the Obliviocene intensifies these threats. Nevertheless, we are not doomed to dislocation and forgetfulness. As we gathered in Brecon Cathedral for these conversations, I was reminded of the central role that memory plays in the Christian narrative. The Edenic fall seems to stem, at least in part, from a failure to remember: Eve misremembers God’s command about the Tree of Knowledge. That failure of memory led to the original exile, the original division between people and the land which they had been commanded to care for. That is not the end of the story, however. Christ was broken for our sins in order that we might be re-membered, restored to right relationship with God and one another and given a re-made heaven and earth to inhabit. In the medieval era, before the Reformation transformed the cathedral interior, there was a large rood screen that pilgrims came from miles to see and kiss. One Welsh poet, Huw Cae Llwyd, responded to the Brecon rood screen by writing, “I am healed by the sight of you.” While this screen has been taken down, Christians continue to gather in the cathedral to eat and drink in remembrance of Christ. And in practicing this act of communal memory perhaps we’ll learn how to become a people who remember well, a people whose lives participate in the healing we have been offered. History’s rents will not be fully repaired in time, but they may yet be made whole in the world re-made by nail-scarred hands.

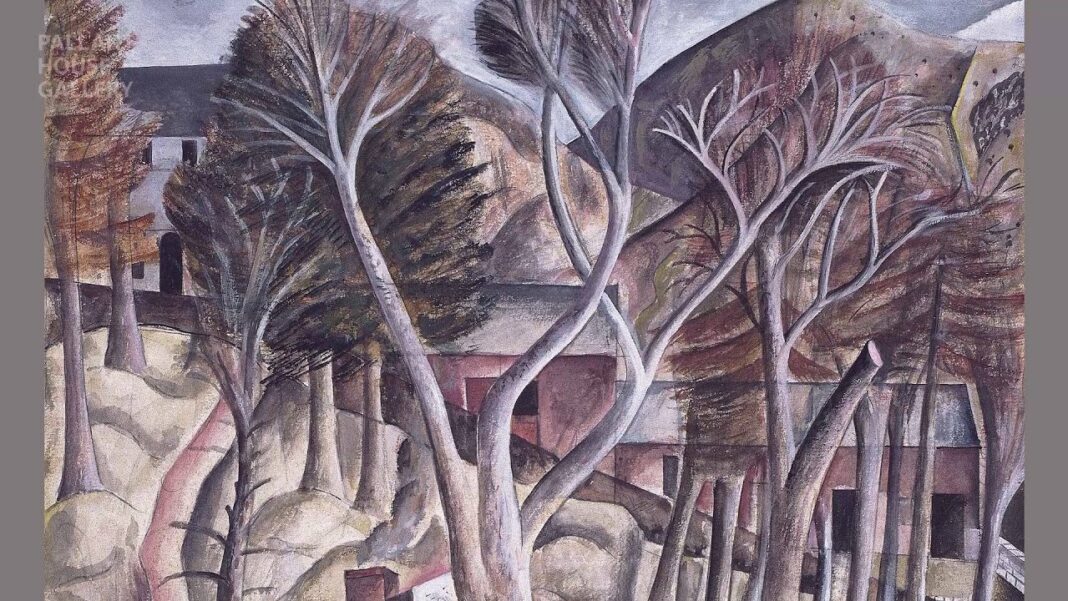

Header painting by David Jones, “Capel-y-ffin”

“Obliviocene”, priceless.

Lovely report on this conference. Makes me all the sadder that in the end we decided we couldn’t get to it because of Covid. But thank you for giving us a taste of it, and of the amazing countryside and history in that part of Wales.

We missed you! But we enjoyed hearing your paper read even in your absence.

Comments are closed.