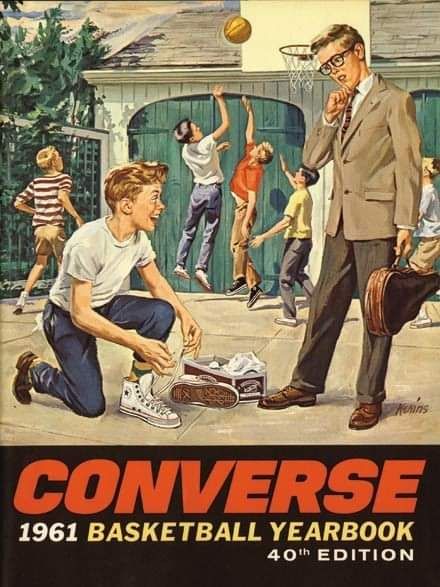

Medanales, NM. I stood on a threshold once, and though it was narrow – just a half shoe size wide – and I wanted more than anything to cross over, I was powerless to do so. I was seven at the time, my foot in one of those metal devices with the sliding brackets that measured a foot’s length and width. And though I alternately stretched my toes and shifted my weight to flatten and expand my foot, the result was the same: just a 2 ½. At that size I could get Keds, a sneaker that was, God knows, better than the brand called Jeepers, which I had to wear at age 5. But not until I hit size 3 could I get a pair of Chuck Taylor All-Stars.

The Chuck Taylors were, to me, beautiful sneakers. Today you can buy them in red, blue, green, hot pink, and camouflage, but back then they came in two colors – black and white – and two styles – high-top or low. The high-tops had a nifty fabric badge on the inside ankle, with a star and the namesake’s signature. But we kids were never sure who Chuck Taylor actually was. For some reason I imagined him as a tall, tough, crew-cut coach, an old-school guy from an earlier era. At any rate, he certainly wasn’t among the great players of the time – a Wilt Chamberlain, a Jerry West, or an Oscar Robertson. But basketball for my peers and me was beside the point when it came to Chuck Taylors, anyhow. For us, the sneakers were made, tailor-made as it were, for a different game, the one to which we were most devoted: kickball.

I don’t know how such things came about, but at my elementary school in Maryland, kickball had evolved into something between a game and a semi-autonomous state. There was no formal authority structuring our play but remarkable order nonetheless – no small achievement for thirty or more energetic kids. We divided neatly into two daily, ongoing games, with third and fourth graders playing in one and fifth and sixth graders playing in the other. At recess, we hurried to our respective diamonds after lunch, chose sides quickly, and then settled down to the work at hand. And there we remained, utterly focused, until the moment we were called back to class.

Despite all the years that have since gone by, I still recall the names of teammates from my third grade season. There was a speedster, Jay Mackey, a force on the base path. And there were the Vassos brothers, Jimmie and Nick, both big and formidable. Jimmie was slightly taller, and we all thought him the better athlete. It was the beefier Nick, however, I would see on TV years later, playing on the offensive line for one of Joe Paterno’s better Penn State teams.

But we had a prince in those days, and it wasn’t one of the Vassos boys, talented as they were. He was Tommy Vitelli, grade 4, and the player always chosen first in our daily drafts. Tommy was left-footed and favored the high-top Chuck Taylors in white. He was on the tall side, strong without being bulky, and fast. But it was his ability to kick the ball that made him a standout. He surely had more home runs than anyone else in our little league, more than all the others combined I suppose. But it was the nature of his kicking that I recall. Like Lou Gehrig, he compressed all the power of his stroke into driving low line drives that always seemed to clear the outfielders’ heads by about the same distance as they did the infielders’. Tommy was also our natural leader, a laconic guy whose even temper established a code none of us dared to break.

And myself as a player? I had my strengths: I had a strong foot on offense, and was a stalwart player in the field, always completely focused on the action. I was, I suppose, in the middle of the pack, but at grade 3 showed solid promise for a productive 4th grade season.

I would never know, however, whether that promise would be fulfilled. Even as we finished the school year, the unseen Fates, the dark Moirai, were weaving a destiny that would take me away from Maryland and set me down in Newton, Massachusetts for one year, 1,000 miles away but somehow in a different, alien universe.

It was not that the people in that land entirely lacked civilization. In fact, my parents had settled on Newton because of the excellent reputation of its education system. But I sensed something strange about my classmates when school began in September of 1970. There was an odd lack of connection amongst them, a missing current, as it were, that might have passed through them but did not. It was a queer thing, really. The specific quality that defined that school, at least for me, was no quality at all but a kind of absence or vacancy. I felt this absence generally that school year, and can recall learning nothing of any of subject I suppose I was taught: math, English, social studies.

But I felt the peculiar vacancy most when it came to games, which held nothing like the grip on the students at the Williams School that they had back in Maryland. I sometimes asked my Newton classmates about kickball, and it was clear that they had heard of it, but there was never enough interest to get a game together. This stood as a disappointment, but one I could do nothing about and so accepted stoically.

Here, too, however, the Fates were weaving destinies that none could predict. Mrs. Anderssen, our sweetly intelligent fourth grade teacher, got it in mind toward the end of the school year to take time on a beautiful May day to play, of all things, a game of kickball. I was transported, of course, but might better have been wary. It is not a sport to be taken lightly, and perhaps it was fare too rich for such an eerily placid school. What could go wrong? Well, what could go wrong on a calm day at sea, when unseen forces bring a rogue wave across your bow?

In any event, the whole class trod out to the field, numbering at least a dozen players on each side. I couldn’t say that they took their positions in the field when the game began, since few understood where to go or what to do once there. Outfielders mingled with infielders and small knots of them formed, the better to chat. And I noticed when the game started that the pitching was much slower than what I was used to in Maryland.

This was not kickball as I knew it, but I felt grateful to be in the game at all and played credibly as the first innings passed. But something worried me. With so many players and the dawdling pace of play, I was anxious about getting at least one turn at the plate. As I watched those slow pitches roll in, I wanted to see what could do to the ball.

When my one turn finally did come round, I was fairly snorting with anticipation. As the pitcher released the ball, I stood five feet behind the plate and watched as it came slowly my way. Finally, the moment fully ripened, I charged like a bull, planted my left foot, and swung at the ball for all I was worth. We talk of hitting the sweet spot in many sports – baseball, tennis, golf – but never before had I struck a ball with sweeter solidity than at that moment. As pure joy surged through me, I turned sharply onto the base path, and I was passing first within moments. Racing on, I sensed disarray among the fielders. Baffled by a ball gone clear over their heads, they seemed uncertain as to how, or even whether, to retrieve it.

I know that they did eventually get the ball back – the game continued, after all – but not in time to catch me. So my kickball heart was sated for a brief, shining moment, with a home run, the only one I can recall in my career.

With that run, our side carried a slim lead into the final half inning, as the other team got their chance to pull even. After one out, they got a runner to first base, but I remained confident we could put them away before losing our lead. Our prospects looked even better when the next player up kicked a dribbly grounder toward second base, which was capably hauled in by my teammate, Tippy Theriault.

Before continuing, a certain fact about kickball must be made clear. So far as I knew, or so far as anyone who actually played the game knew, the rules of kickball were never written down. It is something of a cultural miracle that the young at that time simply absorbed the rules – a gift of the Spiritus Mundi, as it were – and held them in awe. And despite their being unwritten, they are explicit and perfectly clear when it comes to the situation Tippy Theriault faced. He had three ways to get the opposing runner out: holding the ball, he could step on second base; he could toss the ball to a teammate who could then step on the base; or he could throw the ball directly at the runner.

Each way to do the deed, to my eyes, was nearly a sure thing. Yet I watched in mounting horror at what actually occurred. Perhaps undone by choices, Tippy clutched the ball to his chest and fell into a panicky state of paralysis. Then, as the runner passed him by, he tossed the ball, like an old-fashioned set shot, over the head of our man on second, and all the promise of the moment disappeared in a splintered instant.

To say I was disappointed wouldn’t do. I felt more as if some malign Titan had jammed a pry bar into the very heart of our planet and wrenched it utterly off its axis. I ran toward Tippy, bellowing and raging as I went. On reaching him, and the peak of my fury, words failed and, sputtering, I punctuated my demonstration with a brisk slap to his face. And it was if the very air around us burst into flame. Tippy, suddenly berserk, came at me with all he had, and we descended into three or four seconds of mayhem, likely unprecedented in Williams School history.

The very intensity of this fight insured that it wouldn’t last, and the two of us, surprisingly unhurt, were quickly separated. Mrs. Anderssen provided soothing care to Tippy and coaxed him back from the brink of gabbling incoherence. Meanwhile, I was put under the charge of her teaching assistant, a young Maoist from BU, as I recall, who was working toward his teaching credential. All but undone himself, he angrily marched me back to the schoolhouse and put me in some sort of 4th grade penalty box, where I was to stand in darkness, meditating on my sins. But he offered a parting shot before closing the door on me: “How,” he demanded, “can we stop the war in Vietnam, when you can’t even keep from fighting in a game like this!”

As wits have it, time wounds all heels. And it does reasonably well at healing all wounds, too. Though it seems nearly impossible, the world has wobbled on, bent axis and all, for fifty-one years since the events of that afternoon. And by now, I can honestly say that I have come, as the therapists might put it, to a place of acceptance. I have forgiven Tippy Theriault, to start with, for his catastrophic play that day. I hope he has forgiven me, too, for my rather poorly modulated response to it. Likewise with Young Man Mao – any animosity I might once have borne him is surely in the past.

In retrospect, what could I have realistically expected from either of them that day? What did they truly know about kickball – about the marvelous architecture of the game, for instance, in which we found a home and strove so purposefully as young athletes? And what could they have known of its heritage – about the great Tommy Vitelli, for instance, or of the noble uses to which we put our Chuck Taylors in those bright days back in the Old Line State?

But the dark events of that afternoon have remained with me and have prompted a question that I have often wrestled with, fruitfully, I think, but never to a clear decision: Lacking a proper foundation in kickball, what sort of culture, if any at all, could flourish in a Newton, Massachusetts?