Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever really done

For Heaven and the future’s sakes.

– Robert Frost, “Two Tramps in Mud Time”

We stood before the mound of mulch. It looked like a giant creature asleep. We were supposed to spread the mulch over the ground of the school’s outdoor playground. With a machine we could finish the job in an hour. But we did not own such a machine, and renting one would have taken most, if not all, of the profits we were anticipating. The sun sat just above the pine trees that surrounded the playground. It would leave us, soon. The heat, however, had permanent residence. Humidity clung to our skin and clothes like a man in a movie who snatches another man’s shirt collar and threatens to beat him to death. We were already sweating. Had I been asked, I would have told Dad that the decision was up to him. I knew we needed to stay, but in my gut, the desire to tackle this job another day was as strong as the heat was hot. My youthful mind thought hard about sweet tea, TV, and air conditioning. But Dad turned and approached the trailer. He pulled one pin from its bolt and the bolt from its lock. He showed no conflict over whether to stay and work.

Dad told me to grab the shovels from the truck trailer. I grabbed them both, two spades. Flathead shovels were not right for the job. He finished unlocking the trailer gate, lowered it to the pavement, and rolled the wheelbarrow off the trailer and onto the blacktop. He said we should start by wheeling mulch to the part of the playground farthest from the mulch hill and work our way back to the hill. That way, as we got tired, we would have less ground to cover.

We advanced upon the mound and I reared back my spade to jab it into the mulch. Dad told me to wait a minute. Wait and watch, he said, and he pointed at something rising from the mulch. That close to the mulch hill, I could see the steam that Dad saw. I then saw that the entire mound was steaming.

Dad said that mounds like these need to stay damp or they can catch on fire. This one being dry, we needed to proceed with caution. I did not strike my shovel into the hill. Dad scooped up a spade full of mulch. He told me to look at the cavity left from where his shovel had been. More steam rose. The sleeping creature would not awaken and devour us, but even in its lifeless state, it threatened to smother us in its heat. It was not long after we started that our hair, faces, shirts, jeans, socks, and boots were drenched and dripping with sweat. With the heat draped over us like doused blankets, we shoveled mulch and wiped our faces simultaneously. Then the gnats swarmed. Their zingings at our ears, noses, and eyes stayed as constant as waves. So, we shoveled mulch, wiped away sweat, and either ignored or swatted at the gnats.

We worked the job, but everything got heavier the longer we worked. I would stop to breathe or stretch my hands and my back and glance at Dad, who seemed to move without hesitation or error. He labored like a beast of burden, but a beast of burden with a rational mind behind his focused eyes. Because his shirt stuck to his figure, I witnessed his broad shoulders churn, his delts pump, his chest flex, and his biceps rise. Because I had seen him in his running shorts plenty of times, I knew that his legs were built proportionally to his upper body. He’d played football in college and served as a paratrooper for the United States Army. His glutes, hamstrings, quadriceps, and calves were etched and powerful.

Years later I read of Hector, Achilles, Odysseus, and Ajax. Men whose bodies were formidable. Though they might be idealized figures of the poets, before I knew those stories, I knew my father’s form and watched the power he displayed through manual labor. The stories of Greek heroes also clarified my vision of King David’s strength. Perhaps with the exception of Achilles, each of those strong men took pride in his strength yet knew his strength would recede with either injury or age – and that the grave would put an end to their earthly displays of physical power and necessary labor.

Well after nightfall, with the parking lot lights glowing, and the moths flitting around those lights, we finished the job. We straightened the towels we kept over the seats of the Jeep, whenever we were out on a job, and sat down for the drive home. Dad started the engine. Before putting the vehicle in drive, he removed his hat from his head, only to set it back in place. I watched Dad’s forearms, then, as his hands rested on the steering wheel. His forearms were flecked with pieces of mulch. He said that what we had just done felt too much like work.

Work, for Dad, and for others like him, is rarely too much like work and is far more like breathing, like joy. I worked alongside Dad many times. I have also worked alongside other men and women with a disposition towards work like my father’s. They do their labor with skill, creativity, and energy. They rightly earn trust as one to call upon for help with physical jobs. Such people talk of rest, but what they seem to want is a project, activity, the satisfaction of a job well done. They often are uneasy with stillness. And though they would do well to heed an argument for rest and for the deep relationships that are formed in the conversations that come during leisure, I cannot dismiss their appetite for good manual labor.

Consequently, my memories of my dad – and of others I have known like him – include scenes of human beings at work. Those memories will stand like altars long after these individuals have left this world. Those memories will be of them at work, not out of punishment, like Sisyphus, and not out of pride, like Mighty Casey; they are working, rather, out of love, for their work is the work of the Ages, and the Ages outlast the grave.

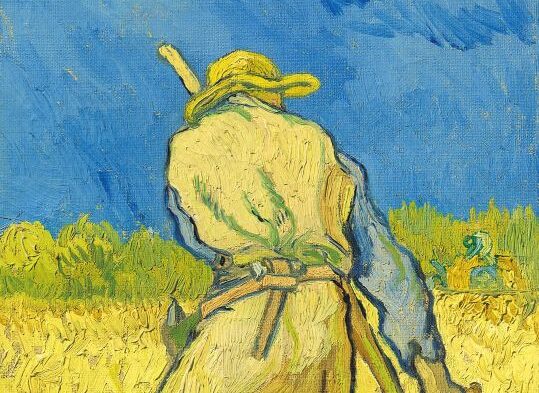

Image Credit: Vincent Van Gogh, “Harvesting,” 1889.

What a tribute to Marks dad, who was undoubtedly working along side him.

The location of this particular event that Mark so vividly portraid and remembered could have been the school ball field at Berean Baptist Church in Fayetteville .

A fitting tribute to a great American and a hard working Dad. 🇺🇸

Mr. Wayne, you are right. And he would pay the same tribute to you.

Perfect tribute, Mark!

Thank you, Josh!

Comments are closed.