“There are incidents in one’s life which…acquire a symbolic value.”

– Dorothy Sayers, Gaudy Night

Princeton, WV. John Wayne’s last film, The Shootist (1976), follows gunfighter J.B. Books (Wayne) to his final shootout, where he chooses to face death in a courageous and honorable manner. His death acquires symbolic value.

Before Books enters the saloon – where he will meet his end – the old gunfighter contends with his landlady, Bond Rogers (Lauren Bacall). The scene takes place in Roger’s kitchen, and the action of the scene entails bread-making, rather than gun-slinging, while Rogers argues for Books to forgo his last showdown. The scene has a symbolic value for two reasons. First, Rogers’ pummeling of the bread dough reveals her frustration with Books. It’s a great example of action that speaks. Next, it is a scene that contains a choice presented and a choice made.

Stories, including film stories, present images of characters in motion in conflict. For, according to Erwin Panofsky, in his 1943 essay “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures,” film stories “are the only visual art entirely alive.” Conflict demands that the characters make choices. Those choices generate more motion. Aristotle’s Poetics contends that story plot must follow a cause-effect pattern fueled by the characters in the story. When the characters face a choice, and when the characters make their choice, especially in film stories, an image of that moment exists. And the image carries a symbolic value.

Our lives, too, are filled with images of choices. The first day of school: bookbags, lunch bags, clean shoes. The commencement ceremony at the end of formal education: cap and gown and diploma. A wedding ceremony: dress and tuxedo and rings. A job application or interview: boxes and references and resumes. The birth of a child: bed and nurse and swaddled infant. The passing of an elder: caskets and caravans and gravesites. The tip-off or first-pitch of a game: chatter and cheer. A game-winning or game-losing play: silence and roar, or silence and woe. The church altar: music and preacher and kneeling penitents.

Much could be said of images of even seemingly insignificant moments. For example, in “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker, the climactic point of the story involves an argument between the antagonist and protagonist over some old quilts. For the antagonist, the quilts represent a history of oppression and survival. That history needs to be preserved in a museum. For the protagonist, the quilts signify a human lineage, a thing one would do well to use everyday, rather than keep on display for ideological grandstanding.

Despite Roger’s bread-making, J. B. Books chose the gunfight, providing an example of how to meet death. But what about the more everyday choices, those that don’t have immediate life or death results? Until we come to the end of our lives, until we ride off into the sunset for our home beyond the sun, we have choices to make.

Consider the following images from three, personal favorite movies. The first comes from The Bourne Supremacy (2004), the second from Michael Clayton (2007), the third from On the Waterfront (1954).

At the end of the final battle scene of The Bourne Supremacy, Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) defeats an assassin who’s hunted Bourne from the beginning of the film, even killing Bourne’s girlfriend. The scene comes to an end in a tunnel in Berlin, Germany. Bourne turns to leave his enemy in the automobile wreck that resulted from their high-speed car chase and fire fight, and when Bourn walks away, he walks out of the tunnel, towards the light. Also in the shot awaits Bourne’s other option: another tunnel, this one into darkness. He has more choices to make, but he first chooses the light. He chooses what is good, and what is good is not always easy.

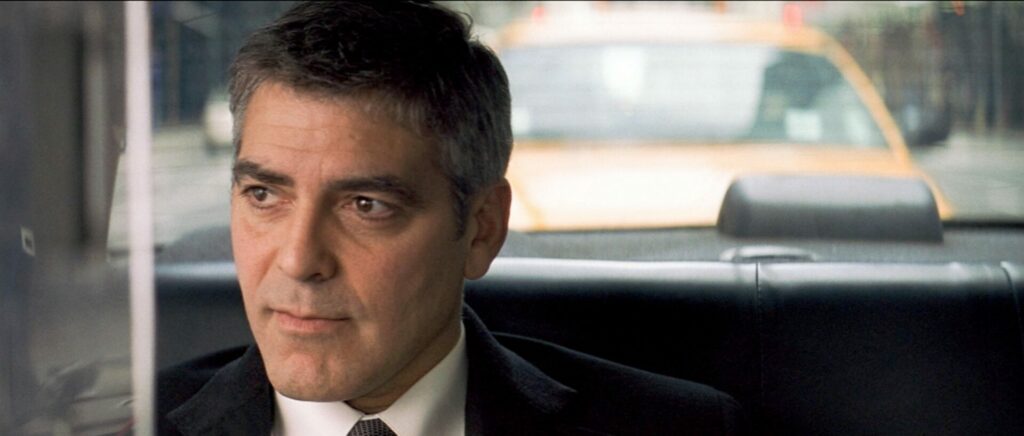

The same year that There Will Be Blood and No Country For Old Men were released, Michael Clayton came to the screen. The final image of that film simply shows Michael Clayton (George Clooney) sitting in the backseat of a New York City taxi cab. This moment comes after Clayton makes a dramatic choice to confront a lethal enemy and put into jeopardy his own legal, yet unethical, career. As the credits roll, we must watch Michael. We must watch him contemplate his recent choices and the choices awaiting him. We hope he will continue to choose the good.

On the Waterfront ends with waterman Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) going fist-a-cuffs with Mafia boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), the man responsible for Malloy’s brother’s death and for the oppression of the other watermen. Friendly and his goons beat Malloy nearly to death. But when the other watermen stand up to Friendly and help raise Terry to his feet, Malloy defies Friendly’s threats and stumbles into the dock warehouse for a day of work. We are left knowing that Malloy will also show up for work the next day and the day after and the day after that.

The images denote choices, but they also denote the choices that have yet to be made. Jason Bourne and Michael Clayton and Terry Malloy have, in the words of Robert Frost, “miles to go before they sleep.” The images bespeak characters choosing the day with the awareness that they will have to continue making and acting on this choice.

Many times, I thought that a visit to the church altar, during an Altar Call, would instantly transform me into a mature Christian, a hero. An Altar Call involves a pastor or evangelist or missionary summoning congregants to kneel before the foot of the pulpit and repent. Those summoned are challenged to repent of sin to be either saved or placed back on track towards sanctification. They are invited to experience a Damascus moment that will transform their lives. Like Langston Hughe’s account in “Salvation,” I made, many times, an emotional response to what was commonly an emotional appeal. I would then live on euphoria. Emotions like that fuel a sprint. They do not strengthen us to walk faithfully. When my euphoria dissipated, a few days or weeks later, I returned to the altar and tried it again. When that pattern proved empty, I considered abandoning the church and God.

Though the Altar Call was certainly and dramatically overused in worship services throughout my adolescence and early twenties, the fault was not in the Altar Call, and the fault was definitely not in the altar. The fault was mine. I mistook one choice at one moment for choices that have to be made every day. Maturity comes through choosing the good under conflict. Someone who takes off into the sunset without having faced the day is either a coward or a Quixote, fancying himself a knight merely because he wants to be one and can wear something approaching knight’s armor.

In his essay “The Gift of Good Land,” Wendell Berry warns that our culture’s heroic genres fail to raise “the issue of life-long devotion and perseverance in unheroic tasks.” And he notes that perhaps paradoxically “it may . . . be easier to be Samson than to be a good husband or wife day after day for fifty years.” These images of repeated, unglamorous choices may be what we need to remind us that momentous choices face us each day. “Choose you this day whom you will serve,” the Old Testament leader, Joshua, charged his fellow Jews. And that choice, while crucial, while fundamental, must also be borne out during a lifetime of choices. As the Apostle James says, “I will shew thee my faith by my works.” Rather than yearning to make one clean choice and then ride into the sunset, let us choose to ride into the day with the courage we need to live faithfully. For such images will remain.

Image Credit: J.M.W. Turner, “Norham Castle, Sunrise” (1845).